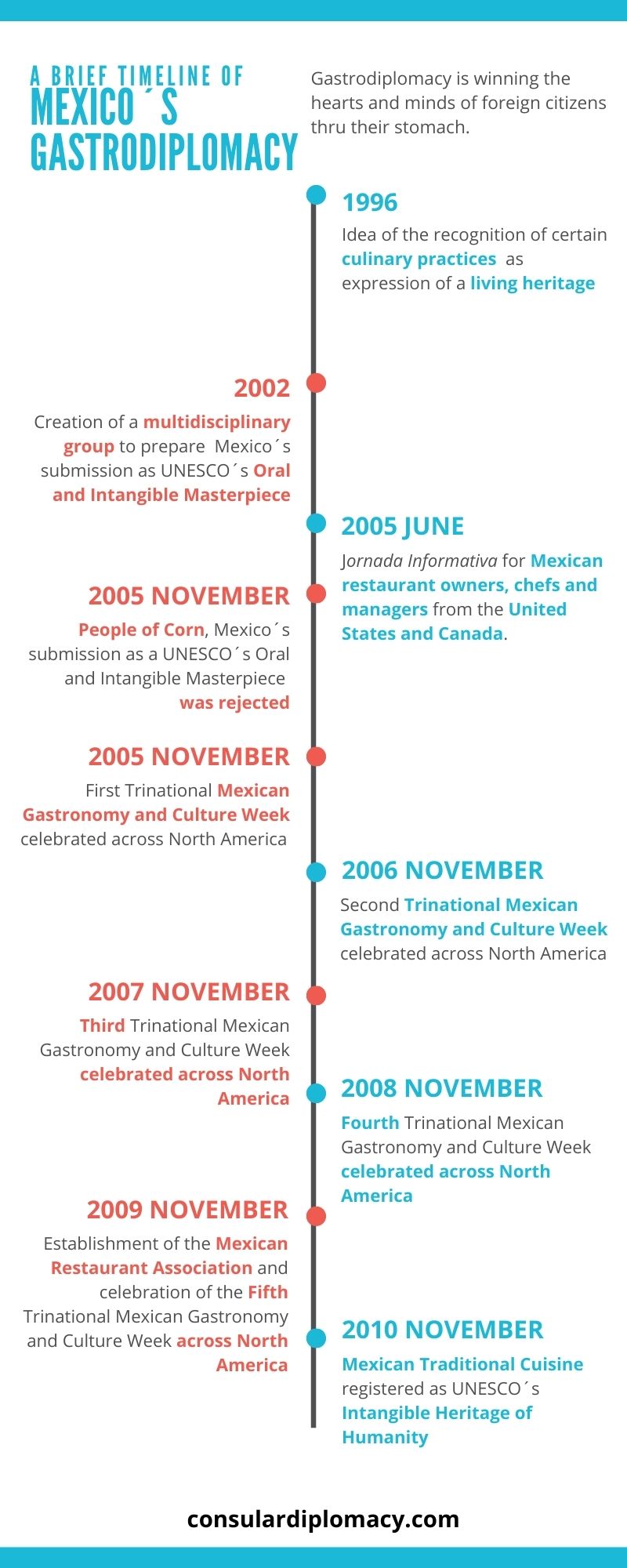

As mentioned in the previous post, Mexico´s Gastrodiplomacy efforts have not been analyzed or recognized; therefore, they are relatively unknown. A few articles cite the diplomatic efforts of the government of Mexico[i] regarding its work to register its traditional cuisine in the list of UNESCO´s Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2010, together with “The Gastronomic meal of the French”. It was the first inscription in the registry of a traditional practice around food. After this historical achievement, other countries such as South Korea, Japan, Turkey, and nations around the Mediterranean have successfully registered a total of 18 “food preparation” elements with the participation of 26 countries. [ii] Before moving in a bit deeper, it is worth asking: do efforts of registering food preparations as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity can be considered Gastrodiplomacy? If not, is this the reason why Mexico´s efforts in this regard have not been included as Gastrodiplomacy, or are there other reasons? Most articles analyzing countries´ Gastrodiplomacy campaigns, particularly the ones about Peru, South Korea, and Japan, included the stated goal of the inscription of its culinary traditions in UNESCO´s list. Therefore, I can assume that this activity forms part of these countries' Gastrodiplomacy efforts. Consequently, Mexico´s actions to achieve this goal must also be considered as Gastrodiplomacy. In 1996, Mexican scholars started the idea of the “recognition of particularly culinary practices as complete expressions of a living and dynamic heritage.”[iii] In 2002, a group of Mexican multidisciplinary academics, led by Yuriria Iturriaga and Cristina Barron, joined forces to begin the preparation of the nomination of the cultural food system of the Mexican people as an Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.[iv] A key player of all these efforts and the follow up is Gloria López Morales, Founder and President of the Conservatorio de la Cultura Gastronómica Mexicana, a non-profit organization registered at the UNESCO. The 2005 nomination of Mexico titled “People of Corn, Mexico´s Ancestral Cuisine. Rituals, Ceremonies and Cultural Practices of the Cuisine of the Mexican People.” was rejected.[v] However, a debate started about the recognition of cuisine and other food and beverage related traditions as part of the registry,[vi] which concluded in 2010 with the inscription of Mexico´s traditional cuisine and the Gastronomic meal of the French as the first ones, as mentioned above. During this time, just before the presentation and, particularly, after the rejection of the registry in late 2005, the government of Mexico began an aggressive but under-the-radar Consular Diplomacy initiative in the United States and Canada, focused on food and cultural heritage. It was part of an overall Gastrodiplomacy strategy to achieve the inscription of Mexican cuisine as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. One of the first activities of the consular Gastrodiplomacy effort was the organization of a “Jornada Informativa”[vii] focused on Mexican chefs and restaurant owners in the United States and Canada in June 2005, a few months before the UNESCO rejected Mexico´s nomination. As a result of the meeting, most of the participants agreed to establish an organization of Mexican restaurants and food distributors in the United States and Canada.[viii] The Mexican Restaurant Association (MERA) held its first national summit in 2009, as part of the 5th Trinational Mexican Gastronomy and Culture Week.[ix] Unfortunately, it later disappeared. Another initiative that developed during that 2005 meeting was the creation of the Trinational Gastronomical Festival or “Semana Trinacional de Gastronomía.” This activity took place around the celebration of the Day of the Dead (November 1st and 2nd, 2005),[x] with the participation of most of the Consulates of Mexico in North America, [xi] together with Mexican restaurants and other organizations, such as Mexican beer distributors, Tequila and Mezcal producers.[xii] The Festival continued for another six years until 2011. All participants of the Jornada Informativa del IME: Programa Trinacional de Gastronomía Mexicana signed a letter to the Director-General of UNESCO in support of Mexico´s nomination to the designation as Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity, that was going to be voted on November 2005.[xiii] As these initiatives demonstrate, there was a comprehensive effort by the government of Mexico, together with non-governmental organizations, to highlight the value of its traditional cuisine, and to have it recognized as an intangible cultural heritage of humanity. It included precise actions in the multilateral arena of UNESCO,[xiv] but also a specific work plan for the Mexican restaurant community in the United States and Canada, supported by the network of Consulates of Mexico in North America. Using Paul Rockewer´s definition of Gastrodiplomacy as a “…concerted public diplomacy campaign by a national government that combines culinary and cultural diplomacy – backed up by monetary investment – to raise its national brand status…”[xv] I believe that Mexico´s efforts clearly can be considered as Gastrodiplomacy. One can ask, was the goal achieved? In the end, in 2010, Mexico´s traditional cuisine was included in the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, reaffirming its position as a robust international cuisine and hopefully winning hearts, minds, and stomachs all across Canada and the United States. Even after these initiatives ended later, the government of Mexico has continued to promote it´s cuisine abroad through different activities. These will be analyzed in another post, hoping to confirm that are actual Gastrodiplomacy actions. [i] See Wilson, Rachel, “Comida Peruana para el Mundo: Gastrodiplomacy, the Culinary Nation Brand and the Context of National Cuisine in Peru” in Exchange: The Journal of Public Diplomacy, Vol. 2, No.. 1, 2011, p. 15; Zhang, Juyan, “The Food of the Worlds: Mapping and Comparing Contemporary Gastrodiplomacy Campaigns” in International Journal of Communication Vol 9, 2015, p. 569; Chappel-Sokol, Sam, “Culinary Diplomacy: Breaking Bread to Win Hearts and Minds” in The Hague Journal of Diplomacy, Vol. 8, 2013, p. 165; and Bestor, Theodore C., “The Most F(l)avored Nation Status: The Gastrodiplomacy of Japan´s Global Promotion of Cuisine”, in Public Diplomacy Magazine, Winter 2004, p.58. [ii] See UNESCO ´s ¨food preparation” category of the registry in the following link https://ich.unesco.org/en/lists?term[]=vocabulary_thesaurus-10 [iii] CONACULTA, “Relatoria, Capítulo 1: El Expediente Pueblo de Maíz, La Cocina Ancestral de México” in Cuadernos Patrimonio Cultural y Turismo, No. 10, 2014, p. 14. [iv] Ibid. Note: thru the Proclamation of Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity 90 intangible masterpieces were recognized in three different sessions (2001, 2003 and 2005). It was not till 2006 when the UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, adopted in 2003, came in to force. Therefore, in the 2008 meeting, those 90 masterpieces were recognized as elements of the Convention. [v] To find out some of the reason why it was rejected read Medina, F. Xavier, “Mediterranean diet, culture and heritage: Challenges for a new conception” in Public Health Nutrition, Vol. 12, Num. 9A, September 2009, p. 1618. [vi] For an analysis of the discussions whether a cuisine or food can be an UNESCO´s intangible cultural heritage of humanity see Romagnoli, Marco “Gastronomic heritage elements at UNESCO: problems, reflections and intepretations of a new heritage category” in International Journal of Intangible Heritage, Vol 14, 2019 p. 158-171 and De Miguel Molina, Maria, et al., “Intangible Heritage and Gastronomy: The Impact of UNESCO Gastronomy Elements” in Journal of Culinary Science and Technology, Vol. 14, No. 4, October 2016, p. 293-310 [vii] The “Jornadas Informativas” or “Migrant-Focused Conferences” are organized by the Institute of Mexican Abroad (IME) of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Mexico that brought to the country different groups of authorities, organizations, and leaders in the U.S. and Canada to learn about Mexico´s efforts toward its immigrant population in those countries and exchange best practices. Each conference or Jornada has a specific theme or focus, such as Health, Financial Education or Gastronomy. For more information about the IME and a description of the Jornadas see: Laglagadore, Laureen Protection through Integration: The Mexican Government´s Efforts to Aid Migrants in the United States, Migration Policy Instituto, January 2010. Additionally visit Jornadas Informativas del IME (in Spanish). [viii] Laglagaron, p. 22. [ix] “Inicia V Semana Trinacional de Gastronomía y Cultura Mexicana”, in Protocolo, October 30, 2009. The national summit of MERA was held in Kansa City, Missouri, during the official opening of the festivities that took place across North America. [x] This was a very clever way to also promote the Day of the Dead, a 2003 UNESCO´s Oral and Intangible Cultural Heritage designation of 2013, for the celebration of the trinational gastronomic week. [xi] Ponce, Karla, “Día de Muertos en Tres Países” in El Universal, October 28, 2005. [xii] Martinez M., Pedro Salvador, “Comiendo con los Muertos” en la Semana de Gastronomia y Cultura Mexicana en EU, Canadá y México”, in Azteca 21, October 24, 2005. [xiii] Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior, 25a Jornada Informativa del IME: Programa Trinacional de Gastronomía Mexicana. SRE, 2005, p. 80. [xiv] See Marco Romagnoli (2019) He states that “Mexico organized an international and scientific meeting in Campeche in 2008 to enhance and promote the heritage value of cuisine.” Its outcome was the “Declaración de Campeche”. Additionally, Mexico supported Peru´s proposal for an expert meeting that took place in France in April 2009, which “paved the way for the acceptance of culinary nominations and inscriptions by UNESCO in 2010”. p. 165 [xv] Rockower, Paul “Recipes for gastrodiplomacy” in Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, Vol. 8, No. 3, 2012, p. 236. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Rodrigo Márquez LartigueDiplomat interested in the development of Consular and Public Diplomacies. Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|