Today is the third anniversary of my blog. As I mentioned in the second-anniversary blog post, it has been a roller-coaster ride with tremendous ups and a few downs. Three years does not seem a lot of time, but many things have changed, for better or worse. I started the blog in September 2020, when the world was closed due to the pandemic. However, significant efforts were made to find a vaccine, thus allowing the world to reopen slowly, even after a series of surges generated by new variants of the virus. For a few years, the world, especially the great powers, has slowly turned economic, financial, data, and people exchanges into geopolitical weapons. To learn more, check out the great work The Power Atlas: Seven battlegrounds of a networked world. Some scholars state that a new era of deglobalization is moving forward as more countries build barriers to the free flow of trade, data, services, and people. The securitization of the economy, particularly semiconductors, critical minerals, and digital technology, is impacting the whole planet. The disruption of Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the exponential race to launch the system that could be the winner has turned the world upside down. There is not a day when a new large language model is not released that supposedly will outperform all others. Students and teachers struggle to find the right approach to using AI, while many workers feel that machine learning will take their jobs and livelihoods. Even though many have asked to pause the development of AI, the race is growing exponentially while governments, societies, and people are trying to make sense of it and find the best approaches to regulate it. An interesting turn is the great concern of AI´s ethics. I clearly understand the worries about making AI work ethically. However, that level of concern about ethical behavior is not shown when talking about humans, governments, and organizations. Why do we not ask for ethical regulations of politicians and governments? Is fighting discrimination in the real world easier than in the digital realm? Three years ago, zoom diplomacy, vaccine diplomacy, and AI diplomacy were brand new terms. Today, even after the reopening of the world, most of the meetings worldwide are being held online, saving money and time but missing the human connection. Digital nomads have turned the globe into their offices, and many people have yet to return, if they ever do, to an office building. Nowadays, diplomacy might be living its fifth evolutionary tipping point, with the confrontation between traditional views of sovereignty and innovative forms of global governance (Neumann, 2020). The big problem is that time is running out, particularly regarding climate change. Just read the headlines this summer regarding the scorching temperatures worldwide. In terms of public diplomacy, the changes in the last years have been difficult to adjust. The transformation of Twitter into something else impacts the digital strategies of many countries, especially for basic accounts. Closing the door of data for research purposes is making it more challenging to listen and engage with audiences. The arrival of deep fakes, like Pope Francis wearing a puffer white jacket, is affecting the credibility of social media, reducing opportunities for governments to engage with foreign audiences. Disinformation is breaking havoc and helping radical views of people, politicians, and governments, making it more difficult to find common ground and collaborations. Regarding consular diplomacy, the pandemic pushed it into the forefront of every ministry of foreign affairs. Foreign ministers and public servants at home, ambassadors, diplomats, and consular officers overseas all work together to help stranded citizens abroad while countries close their borders. Many MFAs are still struggling to meet the demand for documentary services, as the backlog of visas, passports, and other consular documents has not been solved. Lately, there has been a growing amount of research on consular diplomacy, but the field has not yet matured. Many studies have identified consular services as a prime target for using AI systems to manage them. Despite the challenges that humanity confronts today, blogging has been a great experience that has opened the door to things I would not have thought of. Here are some of the milestones that I have achieved in the last three years of having my blog:

I am optimistic that the next three years will be better than the last, maybe just because we are reaching a breaking point. But also because people worldwide want a better future for themselves and their children. Neumann, I. B (2020). Diplomatic tense: A social evolutionary perspective on diplomacy. Manchester Univesity Press. Experimenting with AI Below is a list created by generative AI about the significant milestones of diplomacy in the last three years. Do you agree with the results? Prompt: You are a professor of diplomatic studies. Identify the major changes in the practice of diplomacy that have occurred since January 2020, giving a brief description and using bullets. Please be specific and concise. Bing.chat (creative mode) response: Some of the major changes in the practice of diplomacy that have occurred since January 2020 are:

Bard by Google: Sure, here are the major changes in the practice of diplomacy that have occurred since January 2020:

Perplexity Major changes in the practice of diplomacy since January 2020 include:

Overall, the changing nature of diplomacy in the 21st century requires sustained attention and adaptation to meet the challenges of today and tomorrow. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company.

0 Comments

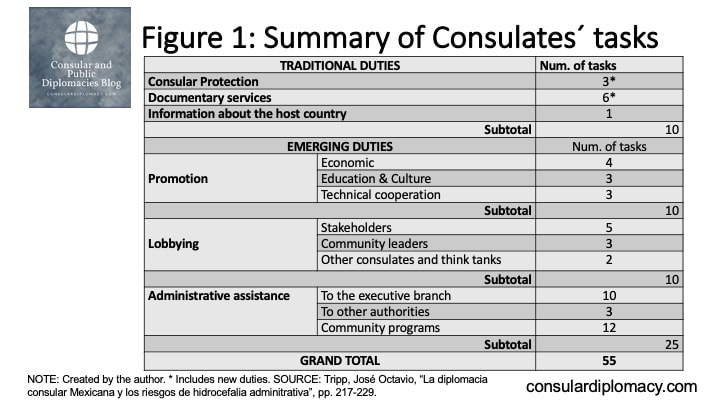

UPDATED JULY 2023 When I started the blog, I did not know a lot of articles and studies about consular diplomacy. I have compiled some resources about the subject in the last two years. The focus is on consular activities related to diplomacy and foreign policy, with a Mexican tilt. Below are some of the works I have identified, which I will update every few months. This list is in alphabetical order but incomplete, and I would greatly appreciate any suggestions. Please feel free to send them in the comments section below or via email. I apologize for not using any reference-management software, but I do not know how to integrate it into the blog. July 2023 update: BOOK CHAPTERS. Arredondo, R. (2023). Las Relaciones Consulares. In Ricardo Arredondo, Diplomacia. Teoría y Práctica, (pp. 315-374). Aranzadi. Celorio, M. (2018). El papel de la diplomacia consular en el contexto transfronterizo: el caso de la CaliBaja. In R. Fernández de Castro (coord.), La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, (pp. 271-285). El Colegio de la Frontera Norte & El Colegio de San Luis. (IN SPANISH) Díaz de León, F. J. & Peláez Millán, V. (2018). La gestión consular integral mexicana en Estados Unidos. Su evolución al servicio de la diáspora y sus objetivos estratégicos. In R. Fernández de Castro (coord.), La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, (pp. 125-152). El Colegio de la Frontera Norte & El Colegio de San Luis. (IN SPANISH) González Gutiérrez, C. & Schumacher, M. E. (1998). La cooperación Internacional de México con los mexicano-americanos en Estados Unidos: El caso del Programa para las Comunidades Mexicanas en el Extranjero. In Olga Pellicer & Rafael Fernández de Castro (coords.), México y Estados Unidos: Las rutas de la cooperación, (p- 1-23). Instituto Matías Romero and ITAM. Fernández, A. M. (2011). Consular Affairs in an Integrated Europe. In Jan Melissen and Ana Mar Fernández, Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, (pp. 97-114). Martinus Nijhoff. Fernández Pasarín, A. M. (2015). Towards an EU Consular Policy. In David Spence and Josef Bátora (eds.), The European External Action Service: European Diplomacy Post-Westphalia, (pp. 356-369). Palgrave Macmillan. García y Griego, M. & Verea Campos, M. (1998). Colaboración sin concordancia: La migración en la nueva agenda bilateral México-Estados Unidos. In Mónica Verea Campos, Rafael Fernández de Castro & Sidney Wintraub (coords.), Nueva Agenda Bilateral en la Relación México-Estados Unidos, (pp. 107-134). Fondo de Cultura Económica Hernández Joseph, D. (2018). Lecciones de la protección consular para la diplomacia consular. In R. Fernández de Castro (coord.), La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, (pp. 91-108). El Colegio de la Frontera Norte & El Colegio de San Luis. (IN SPANISH) Mendoza Sánchez, J. C. (2018). La diplomacia consular ante la demografía y la sociedad de Estados Unidos en el siglo XXI. In R. Fernández de Castro (coord.), La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, (pp. 153-183). El Colegio de la Frontera Norte & El Colegio de San Luis. (IN SPANISH) Tripp, J. O. (2018). La diplomacia consular mexicana y los riesgos de la hidrocefalia administrativa. In R. Fernández de Castro (coord.), La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, (pp. 217-229). El Colegio de la Frontera Norte & El Colegio de San Luis. (IN SPANISH) JOURNAL ARTICLES Chabat, J. (1987). Algunas reflexiones en torno al papel de los consulados en la actual coyuntura. Carta de Política Exterior Mexicana, 7(2). Fernández, A. M. (2008). Consular Affairs in the EU: Visa Policy as a Catalyst for Integration? The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 3(1), p. 21-35. https://doi.org/10.1163/187119008X266164 Fernández, A. M. (2009). Local consular cooperation: Administrating EU internal security abroad. European Foreign Affairs Review, 14(4), p. 591-606. Fernández Pasarín, A. M. (2010). La dimension externa del Espacio de Libertad, Seguridad y Justicia: el caso de la cooperación consular local. Revista CIDOB d’Afers Internacionals, núm. 91, p. 87-104. OPEN ACCESS (In Spanish). González Gutiérrez, C. (1998). Mexicans in the United States: An Incipient Diaspora. Voices of Mexico (43). OPEN ACCESS. Maftel, J. (2020). Application of the Principle of Mutual Consent in Consular Relations between States. Acta Universitatis Danubius, 16(2), p. 88-105. OPEN ACCESS. Melissen, J. (2020). Consular diplomacy's first challenge: Communicating assistance to nationals abroad. Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies, 7(2), p. 217-228. https://doi.org/10.1002/app5.298 OPEN ACCESS. Muro Ruiz, E. (2012). La diplomacia federativa de los gobiernos locales y los consulados mexicanos en Estados Unidos de América, en un multiculturalismo latino. Revista de la Facultad de Derecho de México, 60(254), p. 29-56. https://doi.org/10.22201/fder.24488933e.2010.254.30192 Potter, P. (1926). The Future of the Consular Office. American Political Science Review, 20(2), p. 284-298. Puente, J.I. (1930, January). The Nature of the Consular Establishment. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 78, p. 321-345. OPEN ACCESS. Romero Vara, L., Alfaro Muirhead, A.C., Hudson Frías, E., & Aguirre Azócar, D. (2021). Digital Diplomacy and COVID-19: An Exploratory Approximation towards Interaction and Consular Assistance on Twitter. Comunicación y Sociedad, e7960. https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2021.7960. OPEN ACCESS. Saliceti, A. I. (2011). The Protection of EU Citizens Abroad: Accountability, Rule of Law, Role of Consular and Diplomatic Services. European Public Law, 17(1), pp. 91-109. Schiavon, J. (2015). Consular Protection as State Policy to Protect Mexican and Central American Migrants. Central America-North America Migration Dialogue (CANAMID) Policy Brief #7. GOVERNMENT DOCUMENTS Acuerdo Interinstitucional entre los Ministerios de Relaciones Exteriores de los Estados Parte de la Alianza del Pacífico pare el Establecimiento de Medidas de Cooperación Consular en Materia de Asistencia Consular. (2014, February 10). (In Spanish). Agreement on Consular Assistance and Co-Operation between the Government of the Republic of Latvia, the Government of the Republic of Estonia and the Government of the Republic of Lithuania. (2019, December 6). Instituto Matías Romero (2018, October). Mexico and California’s Strategic Relationship: True Solidarity in Times of Adversity. Foreign Policy Brief 15. Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. Mendoza Yescas, J. & Sotres Brito, X. (2022, August). Acceptance of High-Security Consular Identification Card in Arizona: An Example of Consular Diplomacy. Foreign Policy Brief 21. Instituto Matías Romero. Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. BIBLIOGRAPHY LIST (04/23) BOOKS: Bada, X. & Gleeson, S. (eds.). (2019). Accountability Across Borders: Migrant Rights in North America. The University of Texas Press. Bada, X. & Gleeson, S. (2023). Scaling Migrant Worker Rights: How Advocates Collaborate and Contest State Power. The University of California Press. Especially chapter two: The Mexican Consular Network as an Advocacy Institution. OPEN ACCESS. Berridge, G.R. (2022). Diplomacy: Theory and Practice. 6th edition. Palgrave Macmillan and the DiploFoundation. Carrigan, W.D. and Webb, C. (2013). Forgotten Dead: Mob violence against Mexicans in the United States, 1848-1928. Oxford University Press. Casey, C. A. (2020). Nationals Abroad Globalization, Individual Rights, and the Making of Modern International Law. Cambridge University Press Délano Alonso, A. (2018). From here and there: Diaspora Policies, Integration, and Social Rights Beyond Borders. Oxford University Press. De Goey, F. (2014). Consuls and the Institutions of Global Capitalism. Routledge. Fernández de Castro, R, (coord.). (2018). La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump. El Colegio de la Frontera Norte & El Colegio de San Luis. (IN SPANISH) Gómez Arnau, R. (1990). México y la proteccion de sus nacionales en Estados Unidos. Centro de Investigaciones sobre Estados Unidos de América, UNAM. (IN SPANISH) Græger, N. and Leira, H. (eds.). (2020). The Duty of Care in International Relations: Protecting Citizens Beyond the Border. Routledge. Heinsen-Roach, E. (2019). Consuls and Captives: Dutch-North African Diplomacy in the Early Modern Mediterranean. University of Rochester Press. Hernández Joseph, D. (2015). Protección Consular Mexicana. Ford Foundation & Miguel Ángel Porrúa. (IN SPANISH) Herz, M. F. (1983). The Consular Dimension of Diplomacy: A Symposium. Institute of the Study of Diplomacy, Georgetown University. Hofstadter, C. G. (2020). Modern Consuls, Local Communities and Globalization. Palgrave Pivot. Lafleur, J.M. & Vintila, D. (2020). Migration and Social Protection in Europe and Beyond (Volume 2): Comparing Consular Services and Diaspora Policies. IMISCOE Research Series. OPEN ACCESS Melissen, J. (2005). The New Public Diplomacy: Between Theory and Practice. In J. Melissen (ed.), The New Public Diplomacy: Soft Power in International Relations. (pp. 3-27). Palgrave MacMillan. Melissen, J. and Fernandez, A. M., (eds.) (2011). Consular Affairs and Diplomacy. Martinus Nijhoff. Moyano Pahissa, Á. (1989). Antología Protección Consular a Mexicanos en los Estados Unidos 1849-1900.Archivo Histórico Diplomático Mexicano, Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. (IN SPANISH) Muñoz Martinez, M. (2018). The Injustice Never Leaves You: Ant-Mexican Violence in Texas. Harvard University Press. Platt, D. C. M. (1971). The Cinderella Service: British Consuls since 1825. Archon Books. BOOK CHAPTERS Berridge. G. R. (2022). Consulates. In G.R. Berridge, Diplomacy: Theory and Practice, (pp. 141-157). Palgrave and DiploFoundation. Calva Ruíz, V. (2018). Diplomacia Consular y acercamiento con socios estratégicos. In R. Fernández de Castro (coord.), La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, (pp. 205-216). El Colegio de la Frontera Norte & El Colegio de San Luis. (IN SPANISH) De Moya, M. & Bravo, V. (2021). Conclusion: Lessons Learned and Future Research. In V. Bravo & M. De Moya (eds), Latin American Diasporas in Public Diplomacy, (pp. 311-324). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74564-6_13 Fernández de Castro, R. & Hernández Hernández, A. (2018). Introducción. In R. Fernández de Castro(coord.), La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, (pp. 17-25). El Colegio de la Frontera Norte & El Colegio de San Luis. (IN SPANISH) Fernández Pasarin, A. M. (2016). Consulates and Consular Diplomacy. In C. Constantinou, P. Kerr & P. Sharp (eds.), The Sage Handbook of Diplomacy. Sage Publishing. Gómez Zapata, T. (2021). Civil Society as an Advocate of Mexicans and Latinos in the United States: The Chicago Case. In V. Bravo & M. De Moya (eds.), Latin American Diasporas in Public Diplomacy, (pp. 189-213). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74564-6_8 González Gutiérrez, C. (1997). Decentralized Diplomacy: The Role of Consular Offices in Mexico´s Relations with its Diaspora. In Rodolfo O de la Garza and Jesús Velasco (eds.), Bridging the Border: Transforming Mexico-U.S. Relations, (pp. 49-67). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. González Gutiérrez, C. (2006). Del acercamiento a la inclusión institucional: la experiencia del Insittuto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior. In C. Gónzalez Gutiérrez (coord.), Relaciones Estado-diáspora: aproximaciones desde cuatro continentes, Tomo 1, (pp. 181-220). Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. (IN SPANISH) González Gutiérrez, C. (2018). El significado de una relación especial: las relaciones de México con Texas a la luz de su experiencia en California. In R. Fernández de Castro (coord.), La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, (pp. 253-269). El Colegio de la Frontera Norte & El Colegio de San Luis. (IN SPANISH) Heijmans, M. y Melissen, J. (2007). MFAs and the Rising Challenge of Consular Affairs Cinderella in the Limelight. En K.S. Rana y J. Kurbalija (eds.), Foreign Ministries Managing Diplomatic Networks and Optimizing Value (pp. 192-206). Malta: DiploFoundation. Laveaga Rendón, R. (2018). Mantenerse a la Vanguardia: Desafío para los Consulados de México en Estados Unidos. In R. Fernández de Castro (coord.), La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, (pp. 231-251). El Colegio de la Frontera Norte & El Colegio de San Luis. (IN SPANISH) Leira, H. & Græger, N. (2020). Introduction: The Duty of Care in International Relations. In N. Græger & H. Leira (eds.), The Duty of Care in International Relations: Protecting Citizens Beyond the Border, (pp. 1-17). Routledge. Leira, H. & Neumann, I. B. (2011). The Many Past Lives of the Consul. In J. Melissen & A. M. Fernández, (eds.), Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, (pp. 223-246). Martinus Nijhoff. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004188761.i-334.69 Leira, H. & Neumann, I. B. (2017). Consular Diplomacy. In P. Kerr & G. Wiseman (eds.), Diplomacy in a globalizing world: Theories and Practice. 2nd edition. Oxford University Press. Melissen, J. (2011). Introduction The Consular Dimension of Diplomacy. In J. Melissen & A. M. Fernández, (eds.), Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, (pp. 1-17). Martinus Nijhoff. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004188761.i-334.6 Melissen, J. (2022). Consular Diplomacy in the Era of Growing Mobility. In Christian Lequesne (ed.), Ministries of Foreign Affairs in the World. Diplomatic Series, Vol. 18. (pp. 251-262). Brill Nijhoff. Mendoza Sánchez, J. C., & Cespedes Cantú, A. (2021). Innovating through Engagement: Mexico’s Model to Support Its Diaspora. In L. Kennedy (ed.), Routledge International Handbook of Diaspora Diplomacy. Routledge. Neumann, I. and Leira, H. (2020). The evolution of the consular institution. In I. Neumann, Diplomatic Tense,(pp. 8-25). Manchester University Press. Okano-Heijmans, M. (2011). Changes in Consular Assistance and the Emergence of Consular Diplomacy. In J. Melissen & A. M. Fernández, (eds.), Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, (pp. 21-41). Martinus Nijhoff. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004188761.i-334.13 Okano-Heijmans, M. (2013). Consular Affairs. In A. Cooper et al., (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Modern Diplomacy, (pp. 473-492). Oxford University Press. Rana, K. S. (2011). The New Consular Diplomacy. In K. S. Rana, 21st Century Diplomacy. A Practitioner's Guide. Continuum. Schiavon, J. A. & Ordorica R., G. (2018). Las sinergias con otras comunidades: el caso Tricamex. In R.Fernández de Castro (coord.), La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, (pp. 185-203). El Colegio de la Frontera Norte & El Colegio de San Luis. (IN SPANISH) Torres Mendivil, R. (2018). La diplomacia consular: un paradigma de la relación México-Estados Unidos. In R.Fernández de Castro (coord.), La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, (pp. 109-124). El Colegio de la Frontera Norte & El Colegio de San Luis. (IN SPANISH) Ulbert, J. (2011). A History of the French Consular Services. In J. Melissen & A. M. Fernández, (eds.),Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, (pp. 303-324). Martinus Nijhoff. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004188761.i-334.96 Valenzuela-Moreno, K. A. (2021). Transnational Social Protection and the Role of Countries of Origin: The Cases of Mexico, Guatemala, Bolivia, and Ecuador. In V. Bravo & M. De Moya (eds.), Latin American Diasporas in Public Diplomacy, (pp. 27-51). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74564-6_2 JOURNAL ARTICLES Bada, X., & Gleeson, S. (2015). A New Approach to Migrant Labor Rights Enforcement. Labor Studies Journal,40(1), 32-53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160449X14565112. Birka, I., Klavinš D., & Kits, R. (2022). Duty of Care: Consular Diplomacy Response of Baltic and Nordic Countries to COVID-19. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy, 17(2022), 1-32. https://doi.org/10.1163/1871191x-bja10115. Bravo, V., & De Moya, M. (2018). Mexico’s public diplomacy efforts to engage its diaspora across the border: Case study of the programs, messages and strategies employed by the Mexican Embassy in the United States. Rising Powers Quarterly, 3(3), 173-193. Cárdenas Suárez, H. (2019). La política consular en Estados Unidos: protección, documentación y vinculacion con las comunidades mexicanas en el exterior. Foro Internacional, LIX(3-4), 1077-1113. https://doi.org/10.24201/fi.v59i3-4.2652. (IN SPANISH) Crosbie, W. (2018). A Consular Code to Supplement the VCCR. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 13(2), 233-243. https://doi.org/10.1163/1871191X-11302019 Délano, A. (2009). From Limited to Active Engagement: Mexico’s Emigration Policies from a Foreign Policy Perspective. International Migration Review, 43(4), 764-814. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2009.00784.x. Délano, A. (2014). The diffusion of diaspora engagement policies: A Latin American agenda. Political Geography, 41, 90-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2013.11.007. De la Vega Wood, D. A. (2014). Diplomacia consular para el desarrollo humano: una visión desde la agenda democrática. Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior 101, May-August, 167-185. (IN SPANISH) Durand, J., Massey, D. S. & Parrado, E. A. (1999). The New Era of Mexican Migration to the United States. The Journal of American History, 86(2), 518-536. Gómez Maganda, G. and Kerber Palma, A. (2016). Atención con perspectiva de género para las comunidades mexicanas en el exterior. Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior, No. 107, May-August, 185-202. (IN SPANISH) González Gutiérrez, C. (1999). Fostering Identities: México´s Relations with Its Diaspora. The Journal of American History, 86(2), 545-567. https://doi.org/10.2307/2567045 Græger, N. & Lindgren, W. Y. (2018). The Duty of Care for Citizens Abroad: Security and Responsibility in the In Amenas and Fukushima Crises. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 13(2), 188-210. https://doi.org/10.1163/1871191X-11302009 Hernández Joseph, D. (2012). Mexico’s Concentration Consular Services. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy,7(2), 227-236. https://doi.org/10.1163/187119112X625556. Haugevic, K. (2018). Parental Child Abduction and the State: Identity, Diplomacy and the Duty of Care. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 13(2), 167-187. https://doi.org/10.1163/1871191X-11302010 Leira, H. (2018). Caring and Carers: Diplomatic Personnel and the Duty of Care. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 13(2), 147-166. https://doi.org/10.1163/1871191X-11302007 Leira, H. and de Carvalho, B. (2021). The Intercity Origins of Diplomacy: Consuls, Empires, and the Sea. Diplomatica 3 (1), 147-156. https://doi.org/10.1163/25891774-03010008 Lottaz, P. (2020). Going East: Switzerland´s east consular diplomacy toward East and Southeast Asia. Traverse: Zeitschrift für Geschichte = Revue d´historie 27(1), 23-34. Marina Valle, V., Gandoy Vázquez, W. L., and Valenzuela Moreno, K. A. (2020). Ventanillas de Salud: Defeating challenges in healthcare access for Mexican immigrants in the United States. Estudios Fronterizos, 21 (e043). https://doi.org/10.1080/23340460.2020.1714462 Márquez Lartigue, R. (2023). Beyond Traditional Boundaries: The Origins and Features of the Public-Consular Diplomacy of Mexico. Journal of Public Diplomacy 2(2), 48-68. Martínez-Schuldt, R. D. (2020). Mexican Consular Protection Services across the United States: How Local Social, Economic, and Political Conditions Structure the Sociolegal Support of Emigrants. International Migration Review, 54(4), 1016-1044. Melissen, J. (2020). Consular diplomacy's first challenge: Communicating assistance to nationals abroad. Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies, 7(2), 217-228. https://doi.org/10.1002/app5.298 Melissen, J. & Okano-Heijmans, M. (2018). Introduction. Diplomacy and the Duty of Care. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 13(2), 137-145. https://doi.org/10.1163/1871191X-23032072 Navarro Bernachi, A. (2014). La perspectiva transversal y multilateral de la protección consular. Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior (101), May-August, 81-97. (IN SPANISH) Necochea López, R. (2018). Mexico´s health diplomacy and the Ventanilla de Salud program. Latino Studies(16), 482-502. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41276-018-0145-8 Okano-Heijmans, M. & Price, C. (2019). Providing consular services to low-skilled migrant workers: partnerships that care. Global Affairs, 5(4-5) 427-443. https://doi.org/10.1080/23340460.2020.1714462 Rangel Gomez, M. G., Tonda, J., Zapata, G. R., Flynn, M., Gany, F., Lara, J., Shapiro, I, & Ballesteros Rosales, C. (2017). Ventanillas de Salud: A Collaborative and Binational Health Access and Preventive Care Program. Frontiers in Public Health 5. 30 June. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00151. Schiavon, J. A. & Cárdenas Alaminos, N. (2014). La proteccón consular de la diáspora mexicana. Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior (101), May-August, 43-67. (IN SPANISH) Torres Mendivil, R. (2014). Morfología, tradición y futuro de la práctica consular mexicana. Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior 101, May-August, 69-79. (IN SPANISH) Tsinovoi, A. and Adler-Nissen, R. (2018) Inversion of the “Duty of Care”: Diplomacy and the protection of Citizens Abroad, from Pastoral Care to neoliberal Governmentality. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy (13) 2, 211-232. https://doi.org/10.1163/1871191X-11302017 Xia, L. (2021). Consular Protection with Chinese Characteristics: Challenges and Solutions. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 16 (2-3), 253-274. https://doi.org/10.1163/1871191X-BJA10068. Valenzuela-Moreno, K. (2019). Los consulados mexicanos en Estados Unidos: Una aproximación desde la protección social. INTERdisciplina, 7(18), 59-79. https://www.revistas.unam.mx/index.php/inter/article/view/68460/61387. OTHER WORKS Batalova, J. (2008). Mexican Immigrants in the United States. Migration Policy Institute. 23 April. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/mexican-immigrants-united-states-2006. Bruno, A. y Storrs, K. L. (2005). Consular Identification Cards: Domestic and Foreign Policy Implications, the Mexican Case, and Related Legislation. Congressional Research Services. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/RL32094.pdf. Global Consular Forum. (2016). Seoul Consensus Statement on Consular Cooperation, 27 October. González, C., Martínez, A. & Purcell, J. (2015). Report: Global Consular Forum 2015, Wilton Park, July. Global Consular Forum. Haynal, G., et al. (2013). The Consular Function in the 21st Century: A report for Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada. Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto. Israel, E. & Batalova, J. (2020). Mexican Immigrants in the United States. Migration Policy Institute. 5 November. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/mexican-immigrants-united-states-2019. Kunz, R. (2008). Mobilising diasporas: A governmentality analysis of the case of Mexico. Working Paper Series, “Glocal Governance and Democracy” 3. Institute of Political Science, University of Lucerne. https://zenodo.org/record/48764?ln=en#.YyZZyC2xBaR. Laglagaron, L. (2010). Protection through Integration: The Mexican Government’s Efforts to Aid Migrants in the United States. Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/IME_FINAL.pdf Márquez Lartigue, R. (2021). El surgimiento de la Diplomacia Consular: su interpretación desde México. Unpublished essay. (IN SPANISH) Murray, L. (2013). Conference report: Contemporary consular practice trends and challenges, Wilton Park, October. Global Consular Forum. Noe-Bustamante, L., Flores, A. & Shah, S. (2019). Facts on Hispanics of Mexican origin in the United States, 2017. Pew Hispanic Center. 16 September. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/fact-sheet/u-s-hispanics-facts-on-mexican-origin-latinos/. GOVERNMENT DOCUMENTS Global Affairs Canada. (2017). Evaluation of the Consular Affairs Program. Diplomacy, Trade and Corporate Evaluation Division, Global Affairs Canada. https://www.international.gc.ca/gac-amc/assets/pdfs/publications/evaluation/2018/cap-pac-eng.pdf Gradilone, E. (2012). Diplomacia Consular 2007 a 2012. Ministério das Relações Exteriores (Brazil) and Fundação Alexandre de Gusmão. https://funag.gov.br/biblioteca-nova/produto/1-182-diplomacia_consular_2007_a_2012 Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior. (2018). Población Mexicana en el Mundo: Estadística de la población mexicana en el mundo 2017. 23 July.http://www.ime.gob.mx/estadisticas/mundo/estadistica_poblacion_pruebas.html. Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior. (2021). ‘Revista “Casa de México”’. 22 January. https://www.gob.mx/ime/articulos/revista-casa-de-mexico. Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. (2019). Fortalecimiento de la Atención a Mexicanos en el Exterior, Libro Blanco 2012-2018. (IN SPANISH) OTHER BLOG POSTS (BESIDES THIS BLOG) Márquez Lartigue, R. (2021). Public-Consular Diplomacy at its Best: The case of the Mexican Consular ID card program. CPD Blog. 4 February. https://uscpublicdiplomacy.org/blog/public-consular-diplomacy-its-best-case-mexican-consular-id-card-program. Márquez Lartigue, R. (2021). Public-Consular Diplomacy That Works: Mexico’s Labor Rights Week in the U.S. CPD Blog. 6 October. https://uscpublicdiplomacy.org/blog/public-consular-diplomacy-works-mexicos-labor-rights-week-us. Márquez Lartigue, R. (2022). Public-Consular Diplomacy That Heals: Binational Health Week Program. CPD Blog. 8 June. https://uscpublicdiplomacy.org/blog/public-consular-diplomacy-heals-binational-health-week-program. Manor, I. (2022, January 25). Are Consular Tweets a New Form of Crisis Signaling? Exploring Digital Diplomacy blog. https://digdipblog.com/2022/01/25/are-consular-tweets-a-new-form-of-crisis-signaling/ DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer, or company.  This blog post is dedicated to all the Mexican diplomats and U.S. legal teams that work with death penalty cases involving Mexicans, especially in memoriam of Imanol de la Flor Patiño, an exemplary person. Today, twenty years ago, Mexico sued the United States in the International Court of Justice for violations of the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations (VCCR), specifically Article 36, which provides the right of consular notification to foreign citizens detained abroad. The case concerning Avena and other Mexican nationals against the United States was a milestone in Mexico's assistance to its citizen overseas, particularly in the United States. In March 2004, the Court rendered its judgment against the United States, thus becoming an instrumental decision for the consular protection of the rights of Mexicans arrested north of the border and also for the 52 named cases (Gómez Robledo 2005, p. 183). The Avena case is Mexico's most consequential consular protection case because it overhauled the assistance consulates provide to distressed citizens and raised the relevance of consular affairs inside the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Background In 1976, the United States Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty. In 1993, a Mexican was executed in Texas; he was the first Mexican put to death after the reimposition of capital punishment. His execution was a big issue in Mexico which generated "more than a hundred condemnatory articles in the [Mexican] press, and pronouncements by not only the minister of Foreign Affairs but the President [of Mexico]" (González de Cossío, 1995, p. 102). As a result, Mexico took a series of actions that helped prepare for the presentation of the Avena case in 2003. One immediate step was to interview all Mexicans on death row. As part of the process, consular officials identified a systemic violation of the right to consular notification in capital cases (González Félix, 2009, p. 218-220). In addition, in 1997, Mexico asked the Inter-American Court of Human Rights for an Advisory Opinion (OC-16/99) about the consular notification. It was a multilateral effort and was not bidding; thus, it was not a direct confrontation with the U.S. The Court published its opinion in 1999, stating that foreign individuals have certain rights under the VCCR, such as the rights of information, consular notification, and communications. Besides, it determined that the sending state and its consular officers also have the right to communicate with its detained nationals (Cárdenas Aravena, n.d). In 2000, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Mexico launched a new program to assist Mexicans on death row in the United States. This program complemented the legal training that some Mexican diplomats received as part of the official collaboration with the University of Houston that started in 1989 (see, for example, De la Flor Patiño, 2017 and number 109 of the Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior). Enhancing consular protection With the arrival of President Fox in 2000, Mexico's government stepped up its engagement with the Mexican community in the United States intending to enhance consular protection. Mexico started negotiating a bilateral migration agreement with the recently inaugurated U.S. president, George W. Bush. The government established the Presidential Office for Migrants Abroad, promoted the Mexican Consular ID Card, and created and expanded consular programs such as the Binational Health Week and the Ventanilla de Salud (Health Desk). In early 2002, the country ratified the Optional Protocol concerning the Compulsory Settlement of Disputes of the VCCR, to which the United States was also a party (González Félix, 2009, p. 221-222), thus offering a binding conflict resolution mechanisms. Meanwhile, the number of Mexicans sentenced to death and executed by U.S. authorities increased, creating an uproar in Mexico. In January 1995, there were 23 Mexicans sentenced to death in the U.S. (González de Cossío, 1995, p. 108). The ICJ's Avena Judgment decision of 2004 included 51 cases. From 1997 to 2002, four nationals were put to death in Texas and Virginia (Death Penalty Information Center, n/d). Even President Fox suspended a trip to president's Bush ranch in Texas in August 2002 as a protest of the execution of a Mexican in the same state (Gómez Robledo 2005, p. 178-179). Meanwhile, Paraguay in 1998 and Germany in 1999 requested the intervention of the ICJ regarding the Breard and LaGrand cases related to violations of consular notification rights by U.S. authorities. In Paraguay's case, the proceedings were stopped after the execution of its national in 1998, while the German brother's case continued even after both were put to death in 1999. Both instances were significant for Mexico's consular protection of its nationals on death row. According to Gómez Robledo (2005), after LaGrand's ICJ decision in June 2001, Mexico tried to work with the United States regarding the Mexicans sentenced to death whose rights were violated by local authorities by denying the consular access with no avail (p. 178-179). The Avena Judgment and its repercussions In January of 2003, in a bold action, Mexico presented in the ICJ the Avena case against the United States for violations of Article 36 of the VCCR regarding the death penalty cases of 54 Mexicans in the United States (Covarrubias Velasco, 2010, p. 133-134). The case had significant implications and had very high visibility in Mexico, particularly at a time when the migration to the United States grew very fast, passing from 4.3 million in 1990 to 9.1 million in 2000 (Rosenbloom & Batalova, 2022). After more than a year, which included one provisional measure, on March 31, 2004, the ICJ issued its judgment. In summary, "the ICJ concluded that the United States had violated its obligations under the Vienna Convention [on Consular Relations] by failing to properly notify Mexican nationals of their rights to have Mexican consular officials notified of their arrest, which in turn deprived Mexican consular officers of their right under Article 36 to render assistant to their detained nationals "(Garcia, 2004, p. 14). More significantly, "the Court ordered the United States to provide judicial review to each and every one of the fifty-one Mexicans named in the suit whose Article 36 rights had been violated, and to determine whether the failure to timely advise the consulate of their arrests resulted in "actual prejudice to the defendant." Importantly, the United States judiciary also had to review and reconsider the convictions and sentences as if the procedural default did not exist" (Kuykendall and Knight, 2018, p. 808-809). It was a massive victory for the rights of the Mexicans on death row, as it was mandatory for the U.S. government. The Judgment bound the U.S. to the 51 Mexicans with capital sentences, regardless of the eventual outcome of each case. The Avena case was a milestone for Mexico's consular protection because:

However, not all has been good news. Regarding the demand by the ICJ court that the U.S. review and reconsider the cases of the 51 Mexicans named in the Avena Judgment, the federal government has faced internal challenges. The most important of these was the Supreme Court's decision regarding the case of Medellin vs. Texas (p. 491). In 2008, the Court indicated that the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations is not a self-execution treaty, therefore, the U.S. Congress must legislate so it could become part of the U.S. law (Medellin vs. Texas (p. 491-492). Regardless of U.S. authorities' continuous breach of their international obligations, there have been crucial domestic adjustments. In some cases, State courts decided to review the death penalty cases based on the Avena Judgment and provided relief to Mexicans on death row. In addition, some states "have at least some statutory requirements concerning consular notification…[and] beginning in December 2014, the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedures now provide that at an initial appearance, the judge must inform the defendant" (Kuykendall and Knight, 2018, p. 824) that if they are foreigners, they have the right to contact their consulates. Besides, since the start of the Avena case in 2003, the support for the death penalty in the U.S. has been declining ever so slowly. In conclusion, the Avena case was Mexico's most consequential consular protection case, which enormously influenced the emergence of the country's public-consular diplomacy. References Cárdenas Aravena, C. (n.d). La Opinión Consultiva 16/99 de la Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos y la Convención de Viena de Relaciones Consulares. Covarrubias Velasco, A. (2010). Cambio de siglo: la política exterior de la apertura económica y política. México y el mundo: Historia de sus relaciones exteriores. Tomo IX. El Colegio de México. Death Penalty Information Center, n.d. Execution of Foreign Nationals [in the United States. De la Flor Patiño, I. (2017). Pena de muerte en el condado de Harris, una mirada a través del cristal de la Universidad de Houston. Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior (109), 99-123. Gallardo Negrete, F. (2022, April 27). La pena de muerte en México, una historia constitucional. Este País. Garcia, M. J. (2004, May 17). Vienna Convention on Consular Relations: Overview of U.S. Implementation and International Court of Justice (ICJ) Interpretation of Consular Notification Requirements. Congressional Research Service. Gómez Robledo V., J. M. (2005). El caso Avena y otros nacionales mexicanos (México c. Estados Unidos de América) ante la Corte Internacional de Justicia. Anuario Mexicano de Derecho Internacional Vol. V, 173-220. https://revistas.juridicas.unam.mx/index.php/derecho-internacional/article/view/119/177 González Félix, M. A. (2009). Entrevistas: Pasajes Decisivos de la Diplomacia. El Caso Avena. Interview by C. M. Toro. Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior (86), 215-223. June. González de Cossío, F. (1995). Los mexicanos condenados a la pena de muerte en Estados Unidos: la labor de los consulados de México. Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior (46) 102-125. Spring. Kuykendall, G. & Knight, A. (2018). The Impact of Article 36 Violations on Mexicans in Capital Cases. Saint Louis University Law Journal 62(4), 805-824. Rosenbloom, R. & Batalova, J. (2022, Oct. 13). Mexican Immigrants in the United States. Migration Policy Institute. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company. I am extremely happy to share with you the article Beyond Traditional Boundaries: The Origins and Features of the Public-Consular Diplomacy of Mexico, published in the newest edition of the Journal of Public Diplomacy. You can read it or download it in this link: https://www.journalofpd.com/_files/ugd/75feb6_82201616bab74db6b1f877c8deb734d6.pdf Besides, if you are interested in the origins of Mexico's consular diplomacy, you can read my previous post here. You can also read additional posts about consular diplomacy, such as:

DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company.  1. Introduction Recently, I had the opportunity to finally read the seminal book on Consular Diplomacy titled Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, edited by Jan Melissen and Ana Mar Fernández. This work allowed me to rethink what is Consular Diplomacy. Ten years have passed since its publication in 2011. Since then, there has been more changes to diplomacy in general and the consular institution in particular. An example of the relevance of Consular Diplomacy today is the response of all ministries of foreign affairs to the COVID-19 pandemic that required a massive effort to repatriate and assist nationals stranded overseas as the world closed in March 2020. The book is divided into three sections:

It includes articles about the history and recent developments of consular affairs of Spain, France, the Netherlands, China, Russia, and the United States, as well as consular experiences of the European Union. The order of the book is a little bit odd because it starts with consular affairs´ contemporary issues and ends with the consular history of three European nations. However, it is a great read that has tons of fascinating information and ideas. If you can only read a few chapters, I suggest checking out the following:

In the introduction, Jan Melissen identifies four conceptual or empirical observations about the development of the consular institution:

These four observations are beneficial for the reader, as they help navigate through the book´s twelve chapters and explore the concept of Consular Diplomacy. 2. Reconsidering Consular Diplomacy After reading the book, one of the first things that hit me was that each country has a unique consular affairs history, from China´s recent interest in assisting its citizens overseas to the Netherland´s reliance on honorary consuls. Learning the consular history of six countries gave me a different perspective of Consular Diplomacy in general, and specifically about the development and characteristics of Mexico´s Consular Diplomacy. I think this is one of the reasons that comparative studies in International Relations are so critical. For example, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, millions of Russian citizens suddenly lived in foreign countries, which happened to Mexicans after the 1846-1848 Mexico-U.S. War. In both cases, the two countries' governments had to step up their consular work to assist and protect their nationals, now living abroad. Another example is the problems raised from the extraterritoriality clauses of international treaties with Western powers. In Mexico´s history, foreign government´s interventions on behalf of their citizens were critical in shaping its foreign policy principles. Therefore, learning a bit about the origins of the Capitulations treaties signed between the Ottoman Empire and European powers was enlighten. Halvard Leira and Iver B. Neumann´s explanation about why the Ottoman Empire granted European nations extraterritorial jurisdiction of their own citizens is excellent for understanding a different perspective from the traditional view of European imposition of those terms.[ii] The book clearly demonstrates that the Capitulations had a significant impact on the development of the consular institution, particularly its judicial attributions. Before, I thought that Mexico´s consular institution was distinctive. However, after reading the book, now I realize that each country´s consular affairs had a specific evolution that is different from all others. Of course, there are common patterns and trends, but each nation experiences them in unique ways. The themes are similar, but the differences are in the details. This new perspective is helping me to have a deeper understanding of the differences between the consular services offered by each country, such as the distinction of providing funds for the repatriations of human remains offered by Mexico to only assisting in the paperwork done by the U.S., Canada, and others. This new understanding is making me rethink the concept of Consular Diplomacy, which is closely related to the history of the country´s consular institution. Another realization is that every country, in general, has the same diplomatic objectives, but in consular affairs, it varies depending on its specific evolution and the relationship between the government and its citizens. Therefore, I believe that Consular Diplomacy is hard to generalize. There is a need to look deeper into what Melissen states as “the long-time neglect of the societal dimension of world politics and diplomacy”[iii] to grasp the idea of diplomatic activities in the consular realm. 3. The division between diplomacy and consular affairs persists but is narrowing The second impression of the book is that the link between diplomacy and consular affairs has always been there, but it has changed as societies and the international arena evolved. Even today, after the rise of the Consular Diplomacy, the division between the two still exists. There is not a single path for the relationship between the two. Each country has its own. However, the incorporation of consular responsibilities to the ministries of foreign affairs from the 17th Century onward is a common feature in most nations. The consular history of the six countries demonstrates the highly complex interaction of the two services. To me, their amalgamation in the early 20th Century did not diminish the perception of consular affairs as a Cinderella´s service. It is not till the end of the 20th Century, as Maaike Okano-Heijmans explains in “Change in Consular Assistance and the Emergence of Consular Diplomacy”, that consular affairs become a true priority not only for the foreign ministries but the government as a whole.[iv] It is then, when globalization speeded up, together with the digital revolution and the democratization of diplomacy, when Consular Diplomacy was able to break through its `glass ceiling´ and become an openly acknowledged core activity of foreign ministries. The modernization and standardization processes that consular affairs have endured in the last 20 years to meet the ever-higher expectation of the public is a clear example of the new status of consular services. Even after the unification of the diplomatic and consular services, most countries still see them as separate entities. The existence of two Vienna Conventions (one for each) is the perfect example of this division. By the early 1960s, when the conventions were discussed, the fusion of the two services was widespread. Why was it so difficult to merge both in just one convention? 4. A greater understanding of the evolution of the consular institution. The book allows the reader to understand better the multiple responsibilities that consuls had, from being judges, tax collectors, trade promoters, and sometimes even chaplains.[v] No wonder there is still a lot of misconceptions about what consuls do nowadays. Even the word `Consul´, is still mixed up with `Counsel´ (law-related) and `Councilor´ (city authority), which in the past were some of the main attributions of the position. Through centuries, and as the Westphalia state-system developed, the consular institution experienced a gradual process of specialization of its functions. Consuls slowly were stripped of some of their core responsibilities[vi] and focused on two critical issues of today´s consular affairs: documentary services and assistance to citizens in distress abroad. At the same time, it seems that a process of homogenization took place in international relations that affected the consular institution. As the articles about the six countries exhibit, consular affairs worldwide suffered the same transformations and are now mostly limited to documentary services and the protection of their nationals. Maybe the concentration on these two activities helped in its rise to the top of the foreign policy agenda? In contrast, there is not such massive evolution of the functions of diplomats. Since the early days, their fundamental responsibilities of representation, negotiation, and communication, including information gathering, have changed little, even with drastic advances in communications and transportation. 5. The connection between public and consular diplomacies It is stimulating to see that Melissen links Public and Consular Diplomacies. “In spite of all their differences, consular work and public diplomacy are somehow kindred activities. To all intents and purposes, both are evidence of new priorities and changing working practices in foreign ministries.”[vii] I think the association between public and consular diplomacies is particularly relevant in the visa policies that directly affect the country´s image among the other nation´s citizens, as the article about the EU´s visa policy clearly showcases.[viii] I consider that, in some cases, both go hand-in-hand and are closer than we usually think. In the case of Mexico´s it may be one and the same, as I wrote in my blog post titled “Public-Consular Diplomacy at its Best: The case of the Mexican Consular ID program”. Besides, Diaspora Diplomacy is also related to Public and Consular foreign policy efforts. The idea of the connection between Public and Consular Diplomacies needs to be looked at in a deeper perspective. Hopefully, I can do this in the not-so-distant future. 6. Conclusion Jan Melissen wanted the book to “hopefully break some new ground”[ix], which I think it definitely did. Since its release, there have not been works of such dimensions;[x] therefore, it is still the standard-bearer of Consular Diplomacy and a must-read for anybody interested in the consular institution. Consular Affairs and Diplomacy is an excellent contribution to the field of study, as it associates the history and development of the consular functions with contemporary tendencies of consular affairs. It also demonstrates the always present interrelation of diplomacy and consular services, regardless of its priority ranking. In a time of a drastic reduction of the State in the international arena, consular affairs are an area that has experienced the opposite. This is partly because of the ever-growing demand and expectations of citizens abroad (and their families at home). Also, since the consular function was never part of the great division between foreign and domestic policies.[xi] For me, the work made me think again about Consular Diplomacy, mainly as a result of the relationship between the government and its citizens, not just part of foreign policy and diplomacy. There is definitely a need for more works like Consular Affairs and Diplomacy. Hopefully, there will be more coming as Consular Diplomacy continues to rise in the field of International Relations and Diplomacy studies. You can also read additional posts about consular diplomacy, such as:

[i] Melissen, Jan, “Introduction The Consular Dimension of Diplomacy” in Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, Jan Melissen and Ana Mar Fernández (Ed), 2011, pp. 1-4. [ii] Leira, Halvard and Neumann, Iver B., “The Many Past Lives of the Consul” in Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, 2011, pp. 225-245. [iii] Melissen, Jan, “Introduction” in Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, Jan Melissen and Ana Mar Fernández (Ed), 2011, p. 2. [iv] Okano-Heijmans, Maaike, “Change in Consular Assistance and the Emergence of Consular Diplomacy” in Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, 2011, pp. 21-42. [v] See, for example the consular responsibilities of French consuls in Ulbert, Jörg, “A history of the French Consular Services” in Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, 2011, pp. 307-313. [vi] For example, in France, with the creation of trade attachés in 1919, consulates were stripped from one of their original responsibilities: trade. [vii] Melissen, Jan, “Introduction” in Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, 2011, p. 2. [viii] Wesseling Mara, and Boniface, Jérôme, “New Trends in European Consular Services: Visa Policy in the EU Neighbourhood” in Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, 2011, pp. 115-144. [ix] Melissen, Jan, “Introduction” in Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, 2011, p. 1. [x] Since the book´s publication, there are some very interesting works released, like the The Hague Journal of Diplomacy´s special volume dedicated to `The Duty of Care´, published in 2018, and Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior volume on Consular Diplomacy (2014), and the books La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en Tiempos de Trump (2018), The Duty of Care in International Relations: Protecting Citizens Beyond Borders (2019), and Modern Consuls, Local Communities and Globalization (2020). [xi] Melissen, Jan, “Introduction” in Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, 2011, p. 2. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company.  Following up on my previous blog post about the surge of “new” diplomacies and the discussion of whether these initiatives a real diplomatic instruments or just imposters, today I will analyze the case of Consular Diplomacy. The conclusion is that while Consular Diplomacy meets all the qualifications to be considered a real diplomatic tool to attain a foreign policy goal, the lack of studies seriously hinders its development. Therefore, it is finally leaving Cinderella's status but is not yet considered a princess, like Public or Cultural Diplomacies. Note: The reference to consular affairs as “Cinderella” was made by D.C.M. Platt in his book The Cinderella Service: British Consuls since 1825. Maaike Okano-Heijmans and Jan Melissen used the term in their paper Foreign Ministries and the Rising Challenge of Consular Affairs: Cinderella in the Limelight. 1. Previous post summary “New” Diplomatic Tools: Imposter Diplomacy or the Real Deal? Shaun Riordan and Katharina E. Höne have expressed their concern about the tendency to incorporate into the diplomatic realm all sorts of activities, which carries the risk of losing the meaning of Diplomacy.[i] To uncover Imposter Diplomacy and confirm the realness of new diplomatic tools, Höne proposes that “rather than a categorical rejection [of the new diplomacies], the proper response is to sharpen our intellectual tools and get to work [and] to tell the imposter from the innovator, we need to look closely at diplomacy as a practice, its relation to the state, and the purposes of these new diplomacies.”[ii] In the previous post, I already analyzed Public and Gastronomic Diplomacies. I conclude that the former could be categorized as a new diplomatic tool, while the latter is still too early, despite investments made by various governments.[iii] 2. Consular Diplomacy rising Despite being older than traditional Diplomacy and at one point much more widespread, the consular function has always been relegated. Only now, in the 21st Century, consular services have received greater attention by not only public officials, including diplomats, but also by politicians, regular citizens, and the media. In the paper, Foreign Ministries and the Rising Challenge of Consular Affairs: Cinderella in the Limelight, Maaike Okano-Heijmans and Jan Melissen explain why consular affairs changed from being the Cinderella of diplomacy to be a high priority for the ministries of foreign affairs (MFAs), the general public, the media, and politicians worldwide. However critical the increasing number of terrorist attacks, the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami, the 2010-11 Arab Spring, and, more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic, Okano-Heijmans and Melissen indicate that the greater interest in consular issues did not develop with the arrival of the internet or social media. It arose during the intra-war years and resulted in the integration of diplomatic and consular services.[iv] and later, with the changes in communications, technology, and transportation. One reason why consular issues are just now rising into prominence in the diplomatic world is that the amalgamation of the consular and diplomatic services is relatively recent, from a historical perspective. In 2022 and 2024 will be the 100th anniversary of the two branches' fusion in Norway and the US, respectively. However, it is a lot more recently for other countries like Great Britain (1943) and Italy (1952).[v] I think that the merging of both services has not been totally completed. The view from inside and outside the Foreign Ministries about the two divisions remains separated. For example, there are two different Vienna Conventions, one specific for Diplomatic Relations and the other regarding Consular Relations. This came about when the combination of the two services already happened in many countries. All this is a bit ironic because, as Jan Melissen states in “Introduction The Consular Dimension of Diplomacy” for most ordinary people, the Ministry's face is not a diplomat seating in an embassy, but a consular official either providing documentary services or consular assistance or promoting trade and better relationships with local and state authorities and civil societies.[vi] It is relevant to know that consular services are more in-tuned with the new realities of 21st Century Diplomacy, such as its focus on strengthening performance thru a service-oriented perspective, the familiarity of intermestic issues, and greater collaboration with new partners.[vii] The consular function's qualities help consular affairs be more visible inside and outside the MFA, ascending to a new level. 3. Is Consular Diplomacy a new diplomatic tool? I will now follow Höne´s recommendation of evaluating the new tools by looking at Diplomacy as a practice, its relation to the state, and its purpose. 3.1 The practice of Consular Diplomacy As mentioned before, consular posts predate permanent embassies in Europe for a couple of hundred years. While in the beginning, consuls were not public officials, sometimes performed duties as authorities. In the hey-days of consular affairs, during the 19th Century, consular officials were also involved in diplomatic activities, even if they were not recognized.[viii] From a comparative standpoint, consular affairs is a lot older than almost all diplomatic tools, such as Public, Cultural, and Multilateral Diplomacies. Its problem is that it is considered a technical function, not as crucial as any diplomatic activity. The countries´ little interest in consular affairs is demonstrated by the fact that the first and only international convention on the subject was negotiated in the 1960s. From a practical perspective, I can understand the different visions between diplomats and consuls. The question of representation and what it entails in terms of protocol, image, and status is enormous among the two. It is totally dissimilar to work in the halls of palaces, presidential offices, and the MFAs than in ports, jails, and other local venues. The distinction is a heavy-weight on consuls' images, and even today, when they are no longer seen as Cinderellas, consular officials have not yet arrived at palaces, presidential offices, or foreign ministers´ desks. Consular affairs is an established responsibility of MFAs that date back centuries, and it has developed into a profession and a practice. There are no doubts about Consular Diplomacy's existence and heritage; however, it has not yet reached a point to be recognized as a useful foreign policy instrument, with a few exceptions. The fact that almost none country utilizes the term regularly is a perfect example that still is underrecognized, even if MFAs undertake actions that could fall into its category. 3.2 Relation to the state Despite the growing outsourcing of certain consular functions and the greater collaboration between consulates and authorities, civil society, and their diaspora, it is evident that it is a government´s responsibility to provide consular services to its citizens abroad and other groups. Consular officials in their corresponding districts are the only ones to execute activities such as visiting prisons and jails, issuing passports and birth certificates, and promoting the country´s image in the host nation. It is a non-delegable function restricted to government officials. Therefore, I can attest that Consular Diplomacy fulfills the requirement to be considered a diplomatic tool rather than an imposter. It can only be performed by the government and its representatives. 3.3 Pursuing Foreign Policy goals There is no doubt that consular affairs are a vital function of the ministry of foreign affairs. However, it is a bit more challenging to attest whether these activities help achieve its Foreign Policy (FP) goals. For countries with relatively low immigration and limited travel opportunities for their citizens, consular affairs might be just a public policy that happens to be offered overseas. In contrast, states with significant diaspora communities and extensive traveling communities might incorporate some FP goals into the management of their consular affairs, such as providing efficient consular services to their nationals and foreign citizens or enhancing consular collaboration with other countries. In many cases, the MFA´s primary concern is the domestic dimension rather than an actual foreign policy objective; however, consular cases' reputational impact is quite high and is the main reason for its recent upgrade.[ix] For both types of countries, a high visibility consular case can turn into a diplomatic situation affecting bilateral relations, even making decisions against their national interests.[x] 3.4 Consular Diplomacy´s missing dimension: studies As I did in the Public and Gastronomic Diplomacies cases, I am also reviewing the Consular Diplomacy´s study field. Sadly, in this area, this new diplomatic tool is still in its infancy. The only known course about the topic “Consular and Diaspora Diplomacy” is offered by the DiploFoundation. However, it has not being offered for the last few years, perhaps demonstrating the lack of interest in the subject. As Okano-Heijmans and Melissen indicate, “consular affairs [do not] appeal sufficiently to students of diplomacy to merit much study and reflection;”[xi] therefore, there is a severe absence of studies about this matter. Regarding scholarly work, the only book about the issue is the 2011 Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, edited by Jan Melissen and Ana Mar Fernández. Astonishingly, the book is ten years old, and since then, no new scholarly book about the subject has appeared. There is the book The Duty of Care in International Relations: Protecting Citizens Beyond the Border published in June 2019. Also, The Hague Journal of Diplomacy dedicated the issue #2, Vol. 13, March 2018, to the topic and was titled “Diplomacy and the Duty of Care.” I am not sure if both discuss Consular Diplomacy, as I have not read them yet. In Mexico, a special issue (#101) of the Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior about the subject was published in 2014. Additionally, the book La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en Tiempos de Trump, written from a practitioner's perspective, came out in 2018. I just learned that Brazil´s MFA issued in 2012 a report titled Diplomacia Consular 2007 a 2012. A few countries, like Canada, Australia, and the Netherlands, have sponsor studies about consular affairs, but none of them use the term Consular Diplomacy often. I don´t understand why there is minimal production of scholarly works and practitioners' essays about this matter. Around the world, there are more consular officers than diplomats performing other duties. As mentioned above, consular agents are the faces of the MFAs to citizens overseas and domestic audiences. One reason might be that consular officials are always too busy solving the newest crisis and a high-level consular assistance case or issuing consular documents to write about their experiences. Privacy limitations are also an obstacle for more research, but I am sure they can be overcome to have more studies about consular affairs. Another cause might be the scarcity of funding, if there is money at all, for research in the field; thus, there are no incentives for up-and-coming scholars, universities, and think tanks to tackle the issue. As the Global Consular Forum[xii] has demonstrated, many countries are interested in expanding the collaboration in consular affairs and are willing to exchange best practices; thus, there is no lack of interest in many MFAs about the subject. With consular services’ new visibility and the need to improve them, I believe that Consular Diplomacy research will grow, but it needs a boost. 4. Conclusions: Does Consular Diplomacy is an imposter or the real deal? For a citizen, the consular function does not carry the significance of the “glamour” of diplomatic life, negotiating a world-changing agreement in New York or Geneva's halls. However, in time of need, very few public officials have the preparation, ability, and ingenuity to solve their problems. Consuls are like the police or the fire department; you just call them in an emergency, but they can change your life. There is an enormous need for more consular studies, but not just to evaluate its performance but to contribute to the surge of a real Consular Diplomacy one day. Ironically, Consular Diplomacy fulfills all the qualifications of a “new” diplomatic tool; however, there is such a tiny body of work that it is hard to confirm its realness. Consular Diplomacy as a “new” diplomatic tool is finally out of its Cinderella´s reference; however, there is still a long way to reach the status of a princess. You can also read additional posts about consular diplomacy, such as:

[i] Riordan, Shaun, “Stop Inventing New Diplomacies”, Center on Public Diplomacy Blog, June 21, 2017 and Höne, Katharina E., “Would the Real Diplomacy Please Stand Up!”, DiploFoundation Blog, June 30, 2017. [ii] Höne, Katharina E., 2017. [iii] Márquez Lartigue, Rodrigo, ““New” Diplomatic Tools: Imposter Diplomacy or the Real Deal?” In Consular and Public Diplomacies Blog, February 22, 2021. [iv] Heijmans, Maaike and Melissen, Jan, in Foreign Ministries and the Rising Challenge of Consular Affairs: Cinderella in the Limelight, Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael, June 7, 2006, p. 5. [v] Berrigde, G.R., Diplomacy: Theory and Practice, 5th ed., 2015, p. 136. [vi] Melissen, Jan, “Introduction The Consular Dimension of Diplomacy” in Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, 2011, p. 3. [vii] Melissen, Jan, 2011, pp. 4-6. [viii] Heijmans, Maaike and Melissen, Jan, in Foreign Ministries and the Rising Challenge of Consular Affairs: Cinderella in the Limelight, Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael, June 7, 2006, pp. 3-4. [ix] Heijmans, Maaike and Melissen, Jan, 2006, pp. 6-7. [x] Okano-Heijmans, Maaike, “Changes in Consular Assistance and the emergence of Consular Diplomacy” in in Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, 2011, pp. 24-26. [xi] Heijmans, Maaike and Melissen, Jan, 2006, p. 1. [xii] The Global Consular Forum is “an informal, grouping of countries, from all regions of the world fostering international dialogue and cooperation on the common challenges and opportunities that all countries face today in delivery of consular services.” Wilton Park, “Global Consular Forum 2015 (WP1381)”. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer, or company.  A. Introduction. For most people, there is always confusion about what a Consulate/Consul does and what are the differences with an Embassy/Ambassador. I believe there are several reasons why this mix-up:

However, consular affairs have increased in their relevance in the international arena, and Consular Diplomacy has risen accordingly. As I mentioned in the post about the concept of Consular Diplomacy, a significant development was the creation of the Global Consular Forum (GCF), “an informal, grouping of countries, from all regions of the world fostering international dialogue and cooperation on the common challenges and opportunities that all countries face today in delivery of consular services.”[ii] In this post, I will analyze the GCF and the reports of the three meetings that have taken place. But before, let´s talk a bit about the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations of 1963. The convention was the first and only multilateral agreement on consular relations. It codified into law many practices that were already part of the customary law regulating consular affairs. Previously all the arrangements were bilateral with a few regional ones. The GCF is a way for countries to discuss the changes in consular relations since the convention almost 60 years ago and topics not covered by it, such as dual nationality. So, let´s start with the meeting where the GCF was created. B. The first meeting and establishment of the Global Consular Forum. The first meeting took place in Wilton Park, United Kingdom, in September 2013 with the participation of 22 countries, a representative of the European Commission, and selected academics from around the world.[iii] The Forum´s report is a trove of information for people interested in Consular Diplomacy. It covers a wide variety of topics, from dual nationality issues to surrogacy challenges and assisting citizen with mental health issues to ever-growing expectations of personalized consular services and interest from politicians, I strongly recommend reading the report because it is an excellent summary of consular services' current most critical challenges. The report has six sections which have additional subthemes:

At the meeting, the participants agreed to formalize its Steering Committee that has the responsibility “…to develop an action plan, expand the membership…and improve upon the Forum´s model following this first experience.”[v] The meeting was very valuable due to the following reasons:

Some of the proposals included in the section “Ideas for the future” are essential, so it is worth highlighting them. The “exchange of lessons-learned, best practices and policies on common issued faced by governments will help countries to maximise their resources, avoid ´reinventing the wheel´ when responding to the changing face of consular affairs and to facilitate collaboration.“[vii] Many countries exchange information on consular affairs, but they usually do it bilaterally, with no outside participation. Therefore, the Forum is an excellent addition because, besides government officials, academics were invited. And the meeting reports underline the need to better engage with stakeholders to improve the provision of certain consular services. Another proposal of the first meeting was that “countries could consider jointly engaging academics to translate policy dilemmas into research themes on issues such as global trends affecting the consular function, technological innovation; politically complex legal issues; expectation management; the limits of state-v-individual responsibility; how to leverage private sector influence in consular work; compiling n inventory of lessons learn from past crises, or assistance in drafting a consular agreement template.”[viii] It is a magnificent idea, which would help expand the limited scholarly work available today on Consular Diplomacy. For example, an exciting development afterward was done by the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs by sponsoring a project around the idea of the “duty of care” from 2014 to 2018.[ix] Two of the outcomes of the research was the publication of a special issue of The Hague Journal of Diplomacy titled “Diplomacy and the Duty of Care” in March 2018 (Vol 13, Iss. 2) and the book The Duty of Care in International Relations: Protecting Citizens Beyond the Border in June 2019. Another proposal presented by the GCF was the need to have a “more structured dialogue with external partners involved in consular affairs, such as the travel industry, legal officials, NGOs, technology companies and academia.”[x] I think this is quite necessary, as we saw it at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic; however, it is not being implemented strategically and comprehensively. One idea that could be more difficult to achieve, proposed at the Forum, is to evaluate the possibility of the “co-location, co-protection and co-representation of countries in both crises and also more routine consular representation.”[xi] These ideas present many challenges for MFAs. C) 2nd meeting of the Global Consular Forum (Mexico 2015) The second meeting of the GCF was organized in Cuernavaca, Mexico, in May 2015. As the previous one, a report was published afterward titled “Report: Global Consular Forum 2015.” This time, representatives of 25 countries and the European Union attended the event. However, the report does not mention any scholar's participation in the meeting, So they might not have attended, at least officially, as the previous one. In preparation for the meeting, some Working Groups, with the assistance of the Steering Committee and the Secretariat, developed discussion papers on the six key themes of the conference:

Additionally, improving consular services was an additional key theme discussed during the session. In the section “International legal and policy framework”, the report describes a research paper's results about 57 bi and plurilateral consular agreements. It highlights “common needs and identified areas whereby the VCCR could be supplemented, including the prospect of developing agreed guidelines to facilitate the sharing of good practice.”[xiii] This research demonstrated the commitment of the forum members to promote further studies about consular affairs and diplomacy. The concrete proposal could also streamline the exchange of information regarding consular issues, which could boost the government´s responses. I enjoyed reading some of the lessons-learned of the consular crisis management in the aftermath of the big earthquake that devasted Nepal in April 2015. It reflected the complexity of the situation and the fast-thinking and creative ways consular officials responded. Again, the issues of dual citizenship and consular assistance to persons with mental illness were highlighted in the report, which means are some of the situations that are still on top of the list for consular officials across the world. The inclusion of “migrant workers” as one of the key themes reflects the priority of this issue for Mexico and other members of the Forum. In the article “Providing consular services to low-skilled migrant workers: Partnerships that care,” Maaike Okano-Heijmans and Caspar Price identify the GCF as a “facilitators of [the] efforts …to address the plight of [low-skilled] migrant workers, aiming to protect their rights…”[xiv] The report contains the agreements reached during the second summit of the Global Consular Forum, including:

The second meeting was deemed a success and included some topics previously discussed while also adding new themes relevant to consular affairs. It was agreed to hold the third meeting in 18-months, so preparations began for that. D) 3rd meeting of the Global Consular Forum (South Korea 2016) Seoul, South Korea, was the host city of the third meeting of the GCF in October 2016. Thirty-two countries and the European External Action Service attended. Again, in this gathering, there is no mention of the participation of other than government officials. While reading the “Seoul Consensus Statement on Consular Cooperation,” the first thing I realized was that it has a very different format, compared to the summaries of the previous two meetings, which were published under the Wilton Park seal. The consensus has the traditional format of a statement of an agreement of a multilateral meeting, not a summary of the discussions. This implies that a certain amount of negotiations took place before and/or during the proceedings to agree on the consensus statement's terms. A positive innovation was to mention the Forum's interest to cooperate with small and developing states, so they can also benefit from the mechanisms' efforts.[xvi] As in previous reports, it highlights the key themes discussed: