In the last couple of days, I have been reading the spectacular book Antología Protección Consular a Mexicanos en los Estados Unidos 1849-1900, written by Ángela Moyano Pahissa. After the author reviewed what I think must have been thousands of official documents and correspondence written by consuls of Mexico, the Mexican delegation in Washington, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, she divided the book into five chapters that deal with specific problems:

In each, Moyano Pahissa included a selection of official documents that reflect the ideas, challenges, and solutions regarding these specific problems that resulted from the Mexico - U.S. War of 1846-1848 and the loss of half of its territory. It is incredible to read that some of them have not changed since then. After reading the book, I now better understand the colossal influence that the annexation to the U.S. of the former Mexican territory had on the Mexicans living in those lands and the development of Mexico’s Consular Diplomacy. From having to ratify their land ownership through a complicated and unfair process, to the need to decide in a year the nationality they wanted to have, Mexicans suffered greatly in the United States after 1848. Besides, there was a direct attack not only against their culture but themselves. “Some historians state that in the decade from 1850 to 1860, Anglo-Americans lynched between three to four thousand Mexicans of a total population of ten thousand.”[i] The systematic loss of property rights, in violation of Article VIII of the Guadalupe Hidalgo Treaty, had significant consequences for Mexicans. Even though property requirements to be able to vote were almost eliminated by then, payment of taxes was still a common requirement to vote, thus limiting their possibility to participate in politics and influence policies. Therefore, Mexico’s government had to enhance the defense of its nationals’ rights north of the border, including the establishment of consular offices in places that before was its own country. Back then, Consuls of Mexico had to respond to information requests by the President’s office about high profile cases reported in the press, when they involved Mexicans, either as victims or as perpetrators. They also presented complaints to U.S. authorities for the delay in court cases, the imposition of high cash bail amounts, or extended detention periods. Mexican consular agents also had to be in constant communications with local and state authorities and the Mexican community, creating cooperation networks. Border consulates had additional challenges like smuggling and attacks on Mexican communities by outlaws, and tribes. If all this sounds similar to what Maaike Okano-Heijmans, a scholar of the Clingendael Institute, described as Consular Diplomacy in “Change in Consular Assistance and the Emergence of Consular Diplomacy,” is because it is! The loss of property rights, the problem of questionable citizenship, the attack on Mexican culture and people, combined with widespread discrimination that Mexicans faced after 1848 in the lost territories, catapulted the government of Mexico to develop an incipient Consular Diplomacy, way before it was the norm across the world.[i] Some of the characteristics of today´s Mexican Consular Diplomacy developed during this period, such as:

[i] Moyano, Pahissa, Ángela, Antología Protección Consular a Mexicanos en los Estados Unidos 1849-1900, México, 1989, p. 113. [i] Heijmans, Maaike and Melissen, Jan in Foreign Ministries and the Rising Challenge of Consular Affairs: Cinderella in the Limelight, Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael, June 7, 2006, p. 4. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer, or company.

0 Comments

In the chapter “Consular Diplomacy in the face of U.S. demography and society in the 21st Century,” of the book La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempo de Trump, Ambassador Juan Carlos Mendoza Sánchez explains that demography changes in the United States have resulted in the expansion of nativist movements and anti-immigrant sentiments amongst the white population. He also details Trump´s changes to immigration policies and Mexico´s response to these challenges thru the implantation of an active and innovative Consular Diplomacy. In the section titled “A new demography face that scares the WASP sector,” the Ambassador pinpoints June 18, 2003, as a milestone because it was the day when the Latino community in the U.S. reached 38.8 million turning into the first minority, overpassing the Afro-American population.[i] As a result, alarms rang amongst the conservative white people, and their response to this “invasion” was the creation and expansion of nativist and anti-immigrant policies. Mendoza Sánchez details the history of anti-immigrant regulations in the U.S., starting from infamous California´s Proposition 187 of 1994 to Samuel Huntington´s book Who are we?[ii] Latino population's fast growth in the U.S. resulted in being the majority group in 30 cities, so the Ambassador states that “it is not unfounded the white-population fears of becoming a minority in their own country [and that fear] have slowly developed into anti-immigrant sentiments, and policies to make the U.S. unattractive to those who live there.”[iii] Donald Trump`s presidency is just a new and more radical chapter in the U.S. immigration policy. In the second part of the chapter, Ambassador Mendoza Sánchez explains that it was a radical change in the designation of undocumented migrants as threats to national security and public safety in two Executive Orders signed by the President. He also details some of the multiple changes to immigration policies, guidelines, and enforcement operations to criminalize undocumented immigration, with a particular focus on Mexico´s border and the Latino population.[iv] Another significant change was the end of enforcement priorities; thus, turning every single undocumented immigrant a target. Considering the existence of three million of mixed households meant the possibility of massive deportation that would have tremendous social consequences in the U.S. consequences of the new enforcement guidelines.[v] In the section “New challenges for Mexican Consular Diplomacy,” Mendoza Sánchez emphasizes that immigration policy changes have a direct impact on Mexicans in the U.S. It presents one of the biggest challenges to Mexico´s Consular Diplomacy. He identifies ten of them, but here I only include six:

The Ambassador highlights that there are more Mexican with immigration status than undocumented ones, for the first time in ages.[vii] This fact is unknown in the U.S. and contradicts the current anti-immigrant rhetoric that most Mexicans are undocumented. He explains that undocumented persons tend to live in sanctuary cities, and the implementation of policies to limit resources to those authorities will affect them.[viii] Fortunately, it has not been occurred yet, mostly thru lawsuits. Mendoza Sánchez writes that the Mexican community's geographical dispersion across the U.S. is one of the biggest challenges for consulates that cover large territories. The Mexican government's response was the establishment of the Mobile Consulate program that in the 21st century expanded into the Consulado sobre Ruedas (Consulate on Wheels) initiative.[ix] These activities were crucial for assisting vulnerable Mexicans after Trump´s inauguration.[x] Additionally, he identifies that “developing synergies with pro-immigrant organizations, authorities, other countries’ consulates, and minority groups is one of the most effective activities for consulates under the current circumstances.”[xi] Consular Diplomacy in action. In response to the enhanced anti-immigrant context, the government of Mexico designed a Consular Diplomacy strategy that contained three main activities:

He briefly explains the FAMEU program implemented in 2017 that had a 50 million dollar extraordinary budget. He briefly mentions Local Repatriation Arrangements[xiii] that help Border consulates in the orderly and humanly repatriation of Mexican nationals.[xiv] These arrangements are a clear example of Maaike Okano-Heijmans´ Consular Diplomacy definition because they are “diplomatic” in nature but are negotiated, signed, and implemented locally. Then the Ambassador explains five different programs part of Mexico`s Consular Diplomacy: a)Protection to Mexicans Abroad Innovations (Innovaciones en la proteccion a mexicanos).

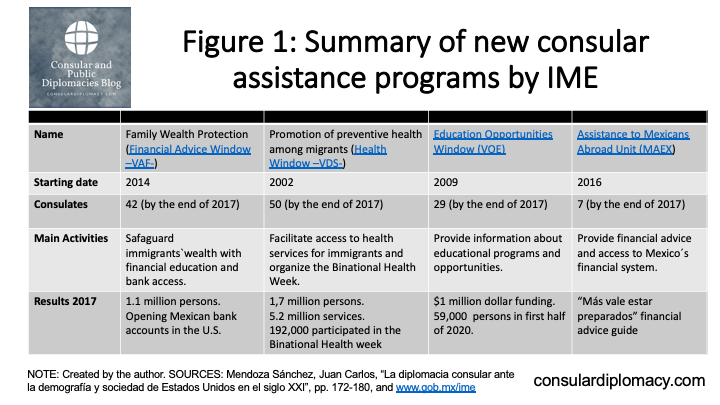

d)Education Opportunities Window (Ventanilla de Oportunidades Educativas). e)Promotion of preventive health among migrants (Promoción de la salud preventiva de los migrantes). Even though Mendoza Sánchez briefly describes each program, I do not include them here. In Figure 1, located at the end of the post, you can find a summary. All of them are innovative consular undertakings of Mexico`s Consular Diplomacy, which some countries are replicating. Most of them are unique and lay outside the traditional consular services offered by most ministries of foreign affairs to their citizens abroad. Four of the five programs highlighted by Ambassador Mendoza Sánchez are under the responsibilities of the Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior (Institute of Mexicans Abroad).[xv] I would like to share an extraordinary achievement of one of them: la Ventanilla de Salud or Health Window. In 2017, the American States Organization granted the “Inter-American Award on Innovation for Effective Public Management” to the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Health of Mexico for the Health Window program in the Social Inclusion category. That year the Health Windows at the consular network provided 5.2 million services to 1.7 million people.[xvi] Conclusion. The chapter is interesting to read as the Ambassador summarizes the origins of the Anglo-American population's growing resentment against immigrants and minorities. He explains that “for the WASP community, the country´s demographic change is a challenge to their way of life, values, and identity; therefore, the hardening of U.S. immigration policies.”[xvii] Mendoza Sánchez states that “to face this new reality, the Mexican Consular Diplomacy has engaged in the largest mobilization of its history with extraordinary programs… [with] the objectives of defending undocumented Mexican migrants´ rights and interests, and supporting them for better integration into their host communities.”[xviii] He also describes some of Consular Diplomacy´s most-forward-looking programs developed to take care of the Mexican community's needs during difficult times. The Ambassador recommends the following:

In this chapter, Ambassador Mendoza Sánchez implicitly highlights one of the essential features of Mexico´s Consular Diplomacy: its adaptability and scalability. As seen in Figure 1, most of the programs described in the chapter started in one or two consulates. After having good results, they were slowly expanded into a country-wide operation at all 50 consulates, and sometimes in other countries with large Mexican populations. [i] Mendoza Sánchez, Juan Carlos, “La diplomacia consular ante la demografía y la sociedad de Estados Unidos en el siglo XXI” in La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, Rafael Fernández de Castro (coord.), Mexico, 2018, p. 154. [ii] Ibid. p. 154-155. [iii] Ibid. p. 157-158. [iv] Ibid. p. 159. [v] Ibid. p. 161. [vi] Ibid. 163. [vii] Ibid. p. 164. [viii] Ibid. p. 165. [ix] Ibid. p. 165-166 [x] Ibid. p. 165 [xi] Ibid. p. 167. [xii] Ibid. p. 168. [xiii] The LRAs are signed by the Consulates of Mexico and DHS agencies. Border LRAs also include the participation of the National Migration Institute of Mexico. Find a public version of the 9 border LRAs here. [xiv] Ibid. p. 169-170. [xv] To learn more about Mexico`s government engagement with its diaspora, read the multiple publications of Alexandra Delano included in Google Scholar. See also Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior # 107 Comunidades Mexicanas en el Exterior, May-August 2016; de Cossío Díaz, Roger, et al., Mexicanos en el Exterior: Trayectoria y perspectivas 1990-2010, Instituto Matías Romero, 2010; Laglagaron, Laura, Protection through Integration: The Mexican Government Efforts to Aid Migrants in the United States, Migration Policy Institute, January 2010; and Rannveig Mendoza, Dovelyn and Kathleen Newland, Developing a Road Map for Engaging Diasporas in Development: A Handbook for Policymakers and Practitioners in Home and Host Countries, International Organization for Migration and Migration Policy Institute, 2012. [xvi] Ibid. p. 179. [xvii] Ibid. p. 180. [xviii] Ibid. p. 180. [xix] Ibid. p. 181. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company.  In this post I analyze the chapter “Mexico´s Integral Consular Management in the United States” written by Francisco Javier Díaz de León and Víctor Peláez Millán of the book La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump (Mexican Consular Diplomacy in Trump´s era). In this chapter, Díaz de León and Peláez Millán evaluate Mexico’s comprehensive consular administration in the United States. They conclude that even though it has been able to face challenges and adapt to new circumstances, it lacks a long-term strategic vision. The chapter is divided into three sections:

In the first section, Díaz de León and Peláez Millán analyze the political context and the Mexican community’s conditions during Donald Trump’s presidency. They highlight the permanent fear experienced by Mexicans, particularly those undocumented, as a result of the aggressive Anti-immigrant and Anti-Mexican rhetoric and policies, at all levels, including some segments of U.S. society. The authors identify the “legitimacy of bullying” against Mexicans across the nation, starting from the White House. Following the President’s lead, many local, county, and state authorities and politicians presented anti-immigrant actions to curb immigration. Simultaneously, the authors indicate that “the Mexican diaspora is not alone; it has the support of a wide range of organizations and collaboration networks of civil rights and pro-immigration groups, legal representation, community development, [and] educational, health and financial services providers…”[i] This support is the result of the work of the 50 Mexican consulates that, since 1990, included community affairs activities to the traditional protection and documentation services.[ii] Recognizing this new situation, in early 2017, the government of Mexico authorized more than 50 million dollars to implement the new strategy entitled Fortalecimiento para la Atención a Mexicanos en Estados Unidos (Strengthened Assistance to Mexicans in the United States), also referred to as FAMEU. Its objective was to support the Mexican community in the United States during these trying times.[iii] Some of the strategy results in 2017 were the establishment of the Centros de Defensoría (Legal Defense Centers) that provided advice to more than 580,000 people and offered legal assistance and representation to 29,000 Mexicans.[iv] Besides, the Centro de Información y Asistencia a Mexicanos (CIAM), Mexico’s 24 hours consular assistance calling center, received nearly 300,000 phone calls, and the Ventanilla de Asesoría Financiera (Financial Advice Desk) benefitted more than 124,000 Mexicans.[v] 2. Integral Consular Diplomacy Management. In the chapter’s second part, Díaz de León and Peláez Millán explain that the consulates of Mexico have a comprehensive work that includes three areas: protection, documentation services, and community affairs, also know as the consular tripod. The authors incorporate to the concept of Mexico’s Consular Diplomacy additional objectives: improve the Mexican community’s well-being and promote their empowerment and inclusion to the host society.[vi] This is an extra element to the Consular Diplomacy ideas that Daniel Hernández Joseph and Reyna Torres Mendivil present in their book’s respective chapters. Díaz de León and Peláez Millán explain that in recent years, the consular network executed an innovation process to improve the quality of its services.[vii] Some of the results were:

Nevertheless, the authors recognize lagging areas, such as training, budget planning, computing equipment, and administrative systems’ reengineering.[ix] Díaz de León and Peláez Millán state that it is indispensable to identify ways to improve and maximize the use of available resources in addition to work with new partners. It will allow the consulates to respond to the immediate needs of the Mexican community while focusing on the strategic goal of promoting their empowerment and integration.[x] 3. Areas of opportunities: Strategic Vision of Mexico’s comprehensive consular management. Regarding areas of opportunities, the authors of the chapter distinguish the following three: a) Assuming a proactive role in the construction of a favorable ecosystem for the Mexican Diaspora. b) Establishing a systematic outreach mechanism towards the 23 million Mexican-American. c) Strengthening the consulate’s political activities that will add value to Mexico’s Consular Diplomacy. The critical element is to incorporate these prospects and the consular services improvement process into a long-term strategic vision that will allow the consulate to achieve the overall foreign policy objectives proactively. Díaz de León and Peláez Millán conclude that the Mexican community appreciates and trusts the Mexican consular network.[xi] Also, Mexico’s Consular Diplomacy enjoys “the legitimacy and credibility to confront the current challenges and take advantage of the opportunities, regardless of U.S. immigration policies and activities.”[xii] Its most significant challenge is to develop a far-reaching plan to benefit the Mexican community north of the border. This reading is a valuable contribution to the concept of the Consular Diplomacy of Mexico as the authors incorporate the Mexican Community’s empowerment as one of its goals. It also poses two crucial questions: a) How to maximize available resources assigned to its consular network? b) How to attract other relevant actors to collaborate in these efforts? Their answer could be the path for the much needed long-term strategic vision. Besides, it is also significant because Díaz de León and Peláez Millán identify three areas of opportunity which could be implemented to continue the transformation of the consular services and programs offered by Mexican consulates in the U.S. [i] Díaz de León, Francisco Javier and Peláez Millán, Victor, “Mexico´s Integral Consular Management in the United States” in La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, Rafael Fernández de Castro (coord.), Mexico, 2018, p. 131. [ii] Ibid. p. 131. [iii] Ibid. [iv] Ibid. p. 132. [v] Ibid. p. 133. [vi] Ibid. [vii] This is similar to other country´s consular services modernization initiatives, as referred by Heijmans, Maaike and Melissen, Jan, in Foreign Ministries and the Rising Challenge of Consular Affairs: Cinderella in the Limelight, Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael, June 7, 2006, p. 7. [viii] Ibid. p. 136. [ix] Ibid. p. 137. [x] Ibid. p. 137-138. [xi] Ibid. p. 148. [xii] Ibid. p. 147. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company.  Today, I will take a break from reviewing the chapters of the book La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en los tiempos de Trump (Mexican Consular Diplomacy in Trump's Era), coordinated by Rafael Fernández de Castro. Instead, I will present Mexico's Cultural Diplomacy towards South America, focusing on Argentina, during the intra-wars years. This is an idea that I had for at least four years, and I am happy that finally, I got the chance to research and write about it. After reading several publications, I realized that this issue and the context when it took place were much more complicated than anticipated. Therefore, I decided that the Cultural Diplomacy strategy of Mexico needs to be visualized as multiple layers. The three perspectives that I propose are the foreign policy goals of enhancing bilateral relationships with South America thru: a) Reciprocal establishment of Embassies; b) cultural exchanges and presentation of Mexico's points of view; and c) traditional diplomatic duties. I believe this will help understand this incredibly complex situation better. The Cultural Diplomacy strategy implemented by the different Mexican administrations during the 1920s and 1930s was not a slam-dunk, nor was it a total failure. However, it established intellectual networks between thinkers and writers from across Latin-America that continued to develop for the rest of the century. 1. International Background. The 1920s and 1930s were turbulent times because there were so many things going on worldwide all at once. The aftermath of World War I resulted in the weakening of European powers and the surge of a still-reluctant United States. The Great Depression broke the international trade system and affected economies across the globe. Besides, the clash of ideas sows the ground for conflicts everywhere. Fascist, Communist, and Capitalist ideologies, combined with nationalism, fought an all-out war, many times in real battlegrounds. The confrontation eventually led to World War II. In Latin America, there were political conflicts and social turmoil after the centennial celebrations of independence. It also saw the rise of dictatorships after coups d 'état against elected governments. 2. Situation in Mexico. At the beginning of the 1920s, Mexico's Revolution was entering a new, less-violent stage, with the "Sonora group" consolidation, but it was still a precarious situation. Álvaro Obregón was elected president in 1920, after the "Agua Prieta" uprising and the assassination of President Venustiano Carranza. The country finally enjoyed some tranquility, but essential issues were still pending, including its relations with the outside world. 2.1 Cultural and Educational renaissance in Mexico. José Vasconcelos, a member of the Ateneo de la Juventud,[i] was the headmaster of the cultural and educational renaissance that Mexico experienced after the Revolution. In the early 1920s, he promoted a cultural explosion spearheaded by the muralist painters Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco. The muralist movement later became an international phenomenon.[ii] Less well-known, but still very influential, was the big boom in literature and political thinkers, that were also members of the Ateneo. Some of them actively worked for the new governments and were the intelligentsia behind the new regime. Some, like Amado Nervo and Alfonso Reyes, were career diplomats. This cultural renaissance is vital to understand the activities that different Mexican administrations during the 1920s and 1930s implemented towards South America. During that time, Mexico City was a magnet for all types of artists and thinkers, as well as political exiles from all over Latin America. 2.2 Mexico's Foreign Policy. "The foreign policy of the governments of the Revolution from Carranza, and with more emphasis from Álvaro Obregón forward, had one major goal: stop the threat to the national sovereignty that represented the U.S. government and business interests. Besides the direct negotiations with Washington, the priority was to fully restore the relations with the major countries of South America, to try, once more, to establish a continental network against U.S. imperialism".[iii] For Mexico, the issue of recognition of the government by other countries, particularly the United States, was of great relevance for several reasons. The first and foremost, it meant that rival groups were not going to get either arms, money, trade, or support from the mighty neighbor to the north, thus weakening them. It also signified the acceptance of the new regime that embraced forward-looking concepts in its Constitution of 1917. Additionally, it meant opening the door for much needed foreign loans and investment to restart the country's economy, devastated during the Revolution. At that time, there was a lot of pressure from abroad, particularly from the United States and the United Kingdom, regarding the implementation of Article 27 of the new Constitution,[iv] especially regarding oil, mining, and haciendas. Additionally, Mexico had to combat the bad image that the U.S. media portraited about the country, the government, and its Revolution. Therefore, the Mexican administrations had to roll out a propaganda operation to present its own view and counter the U.S. perspective.[v] According to Pablo Yankelevich, Mexico's foreign policy actions were a defense mechanism to counter U.S. actions against the Revolution, its ideas, and the new regime. However, the United States government and the business community saw Mexico's internal policies as almost communist actions.[vi] 3. Cultural Diplomacy strategy towards South America. As mentioned, South American countries, particularly Argentina, Brazil, and Chile, represented a crucial diplomatic avenue for Mexico's foreign policy. Therefore, the Revolution's different governments sought a rapprochement with them to counter the U.S. aggressive policies. The overarching goal was to have the support of the region as a buffer to U.S. policies. There were three specific objectives: the establishment of reciprocal embassies, boost exchanges of ideas and the formation of groups supportive of Mexico, and more traditional diplomatic goals such as the creation of direct transportation and communication links, trade promotion, and hosting international conferences.[vii] To achieve these targets, Mexico implemented an ambitious Cultural Diplomacy strategy in South America. Among other activities, these were the most relevant: a) Launch of "Cultural Embassies" and donations of books and other publications. b) Appointment of Mexican intellectuals and writers as the country's representatives. Here are these activities in more detail with a particular focus on Argentina: a) Launch of "Cultural Embassies" and donations of books and other publications. In the early 1920s, José Vasconcelos "promoted the culture and the arts associated with the Revolution thru Cultural Embassies (Embajadas Culturales)."[viii] As part of this activity, in 1921, Antonio Caso toured several South American countries where he "gave conferences and lectures…[and] through the academia Caso sought to bring closer the Mexican culture to those of the host countries."[ix] Later on, as representative of Mexico in Argentina from 1922 to 1924, Enrique González Martínez signed an agreement with the Buenos Aires Popular Libraries to distribute Mexico's publications thru its network, as well as to cultural and literary personalities.[x] "As the conflict with the U.S. worsened during the [Plutarco Elias] Calles regime, there was an extra effort to gain spaces in the Latin American press, so [Mexico] increased the shipment of books, bulletins, and leaflets. Only during the first year of Calles administration, the government sent 230,000 packages of books and periodicals to other countries."[xi] b) Appointment of Mexican intellectuals and writers as the country's representatives. One way to achieve Mexico's foreign policy goals was the designation of renowned thinkers and famous writers as representatives to those countries. The idea was to send cultural Ambassadors, so they support, with their own prestige, the efforts of promoting the bilateral relations.[xii] Also, their status as cultural creators conveyed an image of Mexico as a civilized and pacified nation.[xiii] From early on, Mexican revolutionary governments sent prominent cultural personalities as representatives to South America, particularly to Argentina. In Figure 1, located at the bottom of the post, you can see that most of the Mexican representatives to Argentina in those times were well-known writers, philosophers, and intellectuals, that were an essential part of the renaissance of the arts and education of the new regime.[xiv] Even though Mexican representatives have difficulties obtaining concrete results, "the literature diplomacy (diplomacia de las letras) had the great advantage of giving credibility to most of the Mexican information regarding the Revolution and its national projects."[xv] When Vasconcelos traveled to Argentina in 1922 as representative of president Álvaro Obregón, he and other Mexican delegates "were responsible for establishing a solid network of sympathy towards the revolutionary [regime]."[xvi] Meanwhile, Enrique González Martínez "disseminated the rich Mexican culture, in general, and thru his poetry"[xvii] during his tenure from 1922 to 1924. One of the greatest Mexican writers, Alfonso Reyes,[xviii] was named the first Ambassador to Argentina in 1927 and departed to Brazil in 1930. He later returned to Argentina from 1937 and 1938 before going back to Mexico. As a two-time Ambassador in Argentina, Reyes managed to establish a close relationship with the different vanguard literature groups of Buenos Aires, participating in various initiatives such as the magazine Sur[xix] and Cuadernos del Plata.[xx] As a result of these activities, in January 1928, Ambassador Reyes successfully signed a treaty regarding Literary and Artistic Property, the first of its type signed by two Latin American countries.[xxi] The intellectual networks created during the years when Alfonso Reyes was Ambassador in Argentina produced a continental-wide discussion and began the evolution of the Latin-American identity.[xxii] 4. Evaluation of Mexico's Cultural Diplomacy strategy towards South America. As I mentioned at the beginning of this post, to better understand and evaluate Mexico's diplomatic efforts in South America, these have to been seen from three different perspectives. As the reader will see, Mexico's foreign policy goals in the region were not all failure or success but a mix of both. However, on the cultural side, most were a success in the long run. I) Establishment of reciprocal Embassies with South American countries. It was a highly desired goal by Mexican authorities, even before the Revolution. It finally succeeded during this period. So, in 1922, Brazil and Mexico designated their first Ambassadors. Later, in 1926, the same happened with Guatemala and a year later with Argentina, Chile, and Cuba. With Peru and Bolivia, the opening of embassies occurred in the late 1930s and in the early 1940s with Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Venezuela. Latin American governments were interested in seeing first-hand the changes that were occurring in Mexico. Additionally, some like Brazil disregarded U.S. opposition and opened its embassy before the recognition of the Mexican government by Washington.[xxiii] Besides, during this time, U.S. influence and intervention in the region intensified, so these countries too began to experience some of the pressures and policies as Mexico bore for a long time as its closest neighbor. For Mexico, having embassies meant direct contact with the political elite and other relevant actors. It also opened new opportunities in different fields such as trade, cultural exchanges, and direct transport and communications links. But most importantly, it was a way to balance U.S. influence in the country. So, regarding this foreign policy goal, Mexico was effective in finally achieving a highly-regarded objective. Therefore, its Cultural Diplomacy strategy worked. Of course, it was a mix of different situations that lead to this outcome. II. Cultural exchanges and presentation of Mexico's points of view. Sending highly regarded thinkers as Ambassadors to the Southern Cone, also known as the Diplomacia de las letras (literature diplomacy), allowed the Mexican government to have instant access to many groups, some of whom were closer to the ideals and policies of the Revolution. As the reader saw, besides performing traditional diplomatic duties, Mexico's representatives engaged in multiple cultural endeavors. This resulted in the formation of significant relationships between South American and Mexican intellectuals that lasted for many years. "..Mexican diplomacy had more success in cultural exchanges, built upon political coincidences, cultural affinities, and literary curiosity. And the shadow of that Cultural Diplomacy is still projecting over the bilateral relationship between the two nations [Mexico and Argentina]."[xxiv] So, this effort can be regarded as successful in the long run. And if it is combined with the power of the film industry first and later with TV, most of the people in South America "knew" Mexico from its movies, TV shows, and soap operas as well as artists, musicians, and writers. This helped promote Mexico's positive image across the region for a very long time. While Mexico's representatives worked in establishing great networks of like-minded South Americans, their official diplomatic duties were very tough considering the situation, as the reader will see in the next section. "The great effort to present the Revolution, awaken enthusiasm in universities circles, in segments of the labor movement, in the masonic lodges and in political and intellectuals spaces of the Latin American progressivism, but in the foreign policy arena there were no visible concrete actions toward defending Mexican sovereignty."[xxv] III. Traditional diplomatic duties. I refer to traditional diplomatic duties as the regular activities that a diplomat has to perform, including obtaining the desired support from the host government, promoting trade and investment, and, at that time, having direct transport and communication links between Mexico and the Southern cone. But before presenting the results of this activity, the actual situation has to be considered to appreciate the difficulties that Mexico's representatives faced at that time. In most countries, conservatives regimes were the norm, and little by little military dictatorships controlled most of the continent by the beginning of World War II. These regimes were very close to the Catholic church. When the Cristero conflict (Guerra Cristera) [xxvi] erupted in Mexico's rural parts in 1926, Mexican diplomats had difficulty containing the situation. For example, when Alfonso Reyes arrived in Buenos Aires as Mexico's first resident Ambassador, Argentina's internal situation helped enhance the relationship with Mexico.[xxvii] However, his arrival coincided with the height of the Cristero conflict, which was not well received by Catholics in Argentina and other Latin American countries and the Vatican. As seen, Mexico's most important aim in South America was to balance U.S. intervention in its internal affairs. However, Mexico's "Revolution was able to awaken solidarities, but the Mexican strategy could not generate concrete actions from the Latin American governments.[xxviii] The increasing turmoil and rise of dictatorships also presented an obstacle for Mexico's foreign policy objectives. For instance, "after the coup d 'état in 1930, Argentina's authoritarianism and its foreign policy reduced the space of political coincidences with Mexico. A relationship based on the intellectual field had little possibilities for growth with an Argentinean government that was on the opposite side of Mexico in important issues such as the Spanish Civil War and World War II."[xxix] Besides the lack of concrete support towards Mexico's regime vis a vis the United States, other diplomatic activities did not come to fruition, such as establishing direct transportation and communication links, which affected the possibility of enhancing direct trade exchanges. Multiple obstacles, including economic structural issues, and the changing international situation, prevented the realization of a much-desired outcome.[xxx] One bright spot was the 1923 Pan American Conference, that took place in Chile, "where Mexico could not participate directly. But the country's presence was felt, as they agreed then that a country could not be excluded from attending these conferences, because of its lack of diplomatic relations with the United States."[xxxi] Overall, the Cultural Diplomacy strategy of Mexico towards South America during the 1920s and 1930s had mixed results, but it was positive as a whole. However, I believe it was the foundation for the Latin American intellectual movement that continued developing and mature during the rest of the century. As Guillermo Palacios indicates, "culture was one of the avenues to maintain international contact, when other alternatives such as trade or political alliances were impossible or useless."[xxxii] For Mexico at that time, the Cultural Diplomacy effort to engage with the region seems to be the best option, particularly considering that most South American governments were conservative, and bilateral trade was almost nil. 5. Additional Mexican Cultural Diplomacy activities in other regions. During the same time, some international cultural activities were promoted in the United States, such as the Mexican Arts exhibition of 1930-1931 that circulated in several North American cities, as part of the overall Cultural Diplomacy strategy of Mexico. This should be another blog post as it has its own characteristics. Besides, some Cultural Diplomacy undertakings were geared towards Europe, as can be seen in chapter 4 of the dissertation The Dilemma of Revolution and Stabilisation: Mexico and the European Powers in the Obregón-Calles Era, 1920-1928 written by Itzel Toledo García in November 2016. [i] The Ateneo de la Juventud was an organization founded in 1909 to promote the culture and the arts. Some of its members promoted changes in Mexico before the Revolution and were the intellectual basis for the changes in the education and cultural systems post-revolution. [ii] Alfonso Nieto states that the muralist movement was the only artistic movement outside Europe that had an international reach . Nieto, Alfonso, México y Argentina: Dos Países Unidos por la Cultura: Diplomacia Pública en acción, México, 2011, p. 82. [iii] Palacios, Guillermo, Historia de las Relaciones Internacionales de México 1810-2010, America del Sur, Vol. 4, México, 2011, p. 183. [iv] It changed the property rights of the land and the resources underneath it. Lajous Vargas, Roberta, Las relaciones exteriores de México (1821-2000), México, 2012, p. 174. [v] Yankelevich, Pablo, “Diplomáticos, periodistas, espías y publicistas: la cruzada mexicana-bolchevique en América Latina” in História (Sao Paulo) Vol. 28, No. 2, 2009, p. 497. [vi] Ibid, p. 509. [vii] Palacios, Guillermo, 2011, p. 183-185. [viii] Lajous Vargas, Roberta, 2012, p. 182. [ix] Nieto, Alfonso, 2011, p. 30. [x] Yankelevich, Pablo, “México-Argentina: Itineario de una relación 1910-1930” in TzinTzun, Revista de Estudios Históricos, No. 45, January-June 2007, p. 95. [xi] Yankelevich, Pablo, 2009, p. 498. [xii] Yankelevich, Pablo, 2007, p. 92. [xiii] Neubauer, Celia Guadalupe, “Pedro Henríquez Ureña y Alfonso Reyes en Argentina (1924-1930): una presencia de México en el Río de la Plata” in Secuencia, No. 101, May-August 2018, p. 142. [xiv] Some of the same representatives were assigned to Chile, Brazil, and other South American countries, as well as Europe during these times. [xv] Yankelevich, Pablo, 2007, p. 93. [xvi] Ibid, p. 96. [xvii] Nieto, Alfonso, 2011, p. 30. [xviii] Alfonso Reyes … “Throughout his entire life, during his years in France and Spain, as well as Mexican Ambassador to Argentina and Brazil, and upon his return to Mexico in 1939, Reyes no only facilitated the circulation of his ideas on both sides of the Atlantic, but also propagated this program [to form a Pan-American Intelligentsia], becoming a cultural agent and acting as an interface among various intellectual elites.” Friedman, Federico, “Tightening the Circle: Alfonso Reyes´ Project to form a Pan-American Intelligentsia” in Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos, Vol. 34, No. 1, Winter 2018, p. 90-91. [xix] Victoria Ocampo was the publisher of Sur, which started in 1931. Several Mexican writers and poets wrote articles for the magazine. Alfonso Reyes participated in the Foreign Council or Consejo Extranjero. See Revista Sur. (In Spanish) [xx] Yankelevich, Pablo, 2007, p. 101.. [xxi] Ibid. [xxii] Neubauer, Celia Guadalupe, 2018, p. 137. [xxiii] Palacios, Guillermo, 2011, p. 199. [xxiv] Yankelevich, Pablo, 2007, p. 103. [xxv] Yankelevich, Pablo, 2009, p. 510. [xxvi] The Cristero conflict was an armed combat between Catholics and the government that took place from 1926 and 1929 in the rural areas of the center of the country. The government passed a law that regulated the exercise of the religious services and put the Church under the control of the State. In July 1928 a Catholic killed the then president elected Álvaro Obregón. Many conservative countries frowned upon Mexico´s stand against the Church, as well as other progressive policies such as the agrarian reform. [xxvii] Lajous Vargas, Roberta, 2012, p. 175. [xxviii] Yankelevich, Pablo, 2009, p. 510. [xxix] Yankelevich, Pablo, 2007, p. 103. [xxx] For a brief but complete analysis of the direct transport links and trade efforts between Mexico and Argentina see Zuleta Miranda, María Cecilia, “Alfonso Reyes y las Relaciones México-Argentina: Proyectos y Realidades, 1926-1936” in Historia Mexicana, Vol. 45, No. 4, April-June 1996, pp. 867-905. [xxxi] Yankelevich, Pablo, 2007, p. 97. [xxxii] Palacios, Guillermo, 2011, p. 288. Figure 1. Representatives of Mexico to Argentina 1916-1937

Sources: Mexico y Argentina: Dos Países Unidos por la Cultura: Diplomacia Pública en acción pp. 27-35, Historia de la Relación Bilateral, SRE, and Embajadores de México en Argentina, Acervo Histórico, SRE.

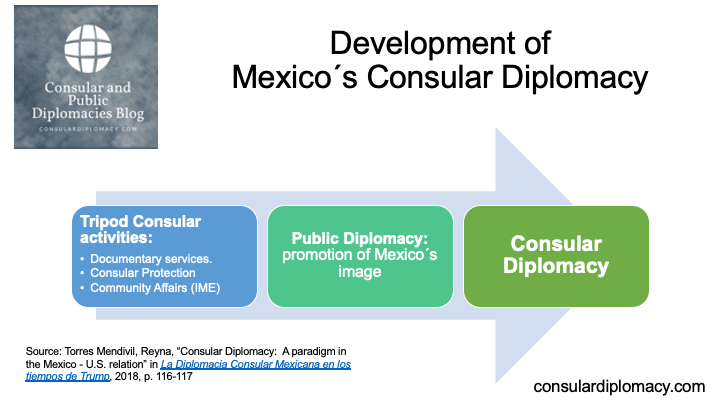

Note: *Information gathered by the author of the blog and from the sources. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company.  This post is the review of chapter five of the book La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en los tiempos de Trump (Mexican Consular Diplomacy in Trump´s Era). In the chapter "Consular Diplomacy: A paradigm in the Mexico - U.S. relation" Ambassador Reyna Torres Mendivil writes that in recent years there has being a change in Mexico´s public discourse that recognizes consular activities as one of the critical elements of the country´s foreign policy.[i] She explains that consular services form part of Mexico´s Ministry of Foreign Affairs' main activities. Also gives examples such as the multiple bilateral consular groups that Mexico has and its active participation in multilateral fora like the Global Consular Forum or the Regional Conference on Migration. By distinguishing the unique characteristics of Mexico´s Consular Diplomacy, Torres Mendivil aims to contribute to the evolution of the definition of the term. She explains that the dividing lines between the diplomatic and consular activities have almost erased. The Ambassador revised the diplomatic functions of the Vienna Conventions on Diplomatic and Consular Relations and found out that of the 13 activities described for a consulate, three are similar to the ones of an Embassy.[ii] Then presents examples of the Mexican consulates´ diplomatic functions.[iii] Torres Mendivil determines that Mexico´s Consular Diplomacy replicates, supports, and compliments at the local level the Embassy´s activities in Washington. And in some cases, these local collaborations later on become formal bilateral agreements.[iv] The Ambassador explains that the need for protection and empowerment of the community pushed the consulates to build bridges with local authorities and even U.S. citizens and other non-traditional actors.[v] In addition to the tripod or regular consular activities,[vi] Torres Mendivil includes a fourth element of the consular action plan: Public Diplomacy. Its objective is the promotion of the image of Mexico. This new dimension is what explains the development from traditional consular assistance into a full-swing Consular Diplomacy.[vii] Here is a diagram of this evolution: The Ambassador explains how Mexico´s consular network implements the country´s Public Diplomacy. She gives different examples of foreign policy activities via Consular Diplomacy, including the collaboration with non-traditional actors such “as shelters for domestic violence victims, financial and credit organizations and religious institutions of all denominations.”[i].

Every week, there is consular presence in one or more media outlets, including scheduled radio and TV programs, where consular officers share relevant information to the Mexican community and the general public. She explains that Mexico has exchange programs similar to those offered by the U.S. (International Visitor Leadership Program), Australia (International Media Visits), and Spain (Programa Internacional de Visitantes). The country developed the “Jornadas Informativas”[ii] , also knowns as IME´s conferences and organized the firsts visits to Mexico for Dreamers in 2014 and 2015. [iii] Additionally, Torres Mendivil explains that the consular network makes enormous efforts to keep alive and visible traditional cultural celebrations. Even though it is hard to measure, she states that there was some influence by Mexico´s consular offices in the popularity of the Day of the Death in the U.S., that end up in the creation of the Disney movie “Coco”.[iv] The political use of anti-immigrant sentiments is not new. It has compelled the consulates to be more strategic and resourceful to protect and empower the Mexican community in the U.S. Ironically, the current administration heavy-handed anti-immigration actions have resulted in greater sympathies and a better understanding of the migrant community reality in the country. At the end of the chapter, Ambassador Torres Mendivil proposes developing the consular network 2.0, which has to be visualized as a bilateral relationship at the local level (relación bilateral al nivel de cancha).[v] It will have to include outreach to multiple actors and local networks. In the end, this will result in a more positive image for Mexico and its diaspora. In the end, a solid consular diplomacy shields Mexico during challenging times, like the one we are living during the Trump administration. The chapter details Mexico´s Consular Diplomacy, adding new characteristics. More importantly, it proposes some ideas for developing a definition of the term, considering the country´s experience and practice. Torres Mendivil briefly mentioned a topic that has developed thru time, which is the popularity of the Day of the Dead in the United States and its implications for Public Diplomacy. I think should be analyzed further. What do you think? If we summarize the previous chapter by Ambassador Hernández Joseph together with the one written by Ambassador Torres Mendivil, three elements of Mexico´s Consular Diplomacy stand out:

These elements could be used to further elaborate a definition of Consular Diplomacy, from the perspective of Mexico´s practice. In the next post, I will review chapter 6 of the book La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en los tiempos de Trump titled “Mexican Comprehensive Consular Management in the United States. Its evolution for the service of the diaspora and its strategic objectives.” [i] Torres Mendivil, Reyna, “Consular Diplomacy: A paradigm in the Mexico - U.S. relation” in La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, 2018, p. 109. [ii] Torres Mendivil, “Consular Diplomacy: A paradigm in the Mexico - U.S. relation”, p. 111. [iii] Torres Mendivil, p. 113-115. [iv] Torres Mendivil, p. 115. [v] Ibid. p. 116. [vi] For Mexico´s consular affairs, tripod or regular consular activities includes documentary services and consular protection for nationals, as well as community affairs activities organized under the umbrella of the Institute of Mexicans Abroad (IME). [vii] Ibid. p. 117. [i] Ibid. p. 119-120. [ii] For a brief description in English of the Jornadas Informativas see ´Migrant-Focus Conferences` on page 19 of the paper Protection through Integration: The Mexican Government's Efforts to Aid Migrants in the United States. [iii] Ibid. p. 119. [iv] Ibid. p. 120. [v] Ibid. p. 123. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company  In this chapter of the book La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump (Mexican Consular Diplomacy in Trump´s Era), Ambassador Daniel Hernández Joseph makes an excellent overview of Mexico’s diplomacy confronting the ever-changing immigration issue in the United States. He identifies elements, as he calls them, that worked well in the past, and some that they did not, that could be used in responding to the challenge that Trump´s administration presents. Hernández Joseph does a brilliant job of synthesizing the most critical periods in the history of Mexico-U.S. migration, which includes Mexico´s most relevant actions. He divides the phases as follow:

By focusing on Mexico’s consular protection of its nationals in the U.S., Ambassador Hernández Joseph highlights the attributes of the rising Consular Diplomacy: its relevance to the country´s overall foreign policy goals and its increase visibility. Therefore, this chapter is valuable as it presents the evolution of the concept of Mexico´s Consular Diplomacy. He explains some of Mexico´s challenges regarding immigration policies and attitudes in the United States, such as the 1930s massive deportation of Mexicans, and the period of bilateral agreements like the Bracero program, that ran from 1942 until 1964. The Ambassador acknowledges the value of the two-way dialogue and the importance of agreements, even if there is no full compliance. Hernández Joseph also recognizes the government of Mexico´s efforts to promote the empowerment of the Mexican community north of the border, indicating that it is one of the critical elements of its Consular Diplomacy. Ambassador Hernández Joseph also acknowledges that an area where Mexico has not succeeded is in improving its image in the United States; notably, it has failed in attaining the recognition by the U.S. society of the contributions made by the Mexican community to the country´s wellbeing.[ii] From Mexico´s previous experiences, the Ambassador identifies four elements that helped the country defend its interests in the United States:

I agree that these four lessons are essential tools that could be displayed to confront the current anti-immigrant movement in the United States, as part of Mexico´s Consular Diplomacy. To conclude, Ambassador Hernández Joseph states that in “…today´s environment, the biggest challenge is to make that the bilateral dialogue effectively results in benefits and protection of the interests of the migrants.”[iv] As we can see, Mexico´s practice of Consular Diplomacy is broader and deeper than the recognized definition of the term described by Maaike Okano-Heijmans.[v] In this case, as a country that has a large population living overseas, migration bilateral negotiations and issues are the core of its Consular Diplomacy efforts. And it is essential to remember that the agreements and actions have to be brought to the operational level by each consulate. It is remarkable to realize that some of these activities that are now considered Consular Diplomacy were already being implemented by the consulates of Mexico in the United States a century ago. So we need a reevaluation of these activities in light of this new academic framework. An exciting twist about Consular Diplomacy that needs to be further explored is that while the center of the actions is to assist and protect its own citizens abroad, most of the consular activities are undertaken via partnerships with local organizations, authorities, and citizens of the host country. So here we have a case of Public Diplomacy with the foreign policy objective of helping its nationals overseas, with the support of local actors. I recommend this chapter because it presents a summary of Mexico´s consular protection activities in the United States and identifies lessons for today´s Consular Diplomacy challenges. [i] Hernández Joseph, Daniel, “Lecciones de la protección consular para la diplomacia consular” in La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, 2018 p. 92-95. [ii] Hernández Joseph, Daniel, “Lecciones”, 2018 p. 103. [iii] Hernández Joseph, Daniel, Ibid. p. 103-105. [iv] Hernández Joseph, Daniel, Ibid. p. 105. [v] See previous post on Consular Diplomacy LINK and Okano-Heijmans, Maaike, “Change in Consular Assistance and the Emergence of Consular Diplomacy”, Netherlands Institute of International Relations ´Clingendael´, February 2010, p.1. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer, or company.

|

Rodrigo Márquez LartigueDiplomat interested in the development of Consular and Public Diplomacies. Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|