UPDATED JULY 2023 When I started the blog, I did not know a lot of articles and studies about consular diplomacy. I have compiled some resources about the subject in the last two years. The focus is on consular activities related to diplomacy and foreign policy, with a Mexican tilt. Below are some of the works I have identified, which I will update every few months. This list is in alphabetical order but incomplete, and I would greatly appreciate any suggestions. Please feel free to send them in the comments section below or via email. I apologize for not using any reference-management software, but I do not know how to integrate it into the blog. July 2023 update: BOOK CHAPTERS. Arredondo, R. (2023). Las Relaciones Consulares. In Ricardo Arredondo, Diplomacia. Teoría y Práctica, (pp. 315-374). Aranzadi. Celorio, M. (2018). El papel de la diplomacia consular en el contexto transfronterizo: el caso de la CaliBaja. In R. Fernández de Castro (coord.), La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, (pp. 271-285). El Colegio de la Frontera Norte & El Colegio de San Luis. (IN SPANISH) Díaz de León, F. J. & Peláez Millán, V. (2018). La gestión consular integral mexicana en Estados Unidos. Su evolución al servicio de la diáspora y sus objetivos estratégicos. In R. Fernández de Castro (coord.), La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, (pp. 125-152). El Colegio de la Frontera Norte & El Colegio de San Luis. (IN SPANISH) González Gutiérrez, C. & Schumacher, M. E. (1998). La cooperación Internacional de México con los mexicano-americanos en Estados Unidos: El caso del Programa para las Comunidades Mexicanas en el Extranjero. In Olga Pellicer & Rafael Fernández de Castro (coords.), México y Estados Unidos: Las rutas de la cooperación, (p- 1-23). Instituto Matías Romero and ITAM. Fernández, A. M. (2011). Consular Affairs in an Integrated Europe. In Jan Melissen and Ana Mar Fernández, Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, (pp. 97-114). Martinus Nijhoff. Fernández Pasarín, A. M. (2015). Towards an EU Consular Policy. In David Spence and Josef Bátora (eds.), The European External Action Service: European Diplomacy Post-Westphalia, (pp. 356-369). Palgrave Macmillan. García y Griego, M. & Verea Campos, M. (1998). Colaboración sin concordancia: La migración en la nueva agenda bilateral México-Estados Unidos. In Mónica Verea Campos, Rafael Fernández de Castro & Sidney Wintraub (coords.), Nueva Agenda Bilateral en la Relación México-Estados Unidos, (pp. 107-134). Fondo de Cultura Económica Hernández Joseph, D. (2018). Lecciones de la protección consular para la diplomacia consular. In R. Fernández de Castro (coord.), La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, (pp. 91-108). El Colegio de la Frontera Norte & El Colegio de San Luis. (IN SPANISH) Mendoza Sánchez, J. C. (2018). La diplomacia consular ante la demografía y la sociedad de Estados Unidos en el siglo XXI. In R. Fernández de Castro (coord.), La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, (pp. 153-183). El Colegio de la Frontera Norte & El Colegio de San Luis. (IN SPANISH) Tripp, J. O. (2018). La diplomacia consular mexicana y los riesgos de la hidrocefalia administrativa. In R. Fernández de Castro (coord.), La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, (pp. 217-229). El Colegio de la Frontera Norte & El Colegio de San Luis. (IN SPANISH) JOURNAL ARTICLES Chabat, J. (1987). Algunas reflexiones en torno al papel de los consulados en la actual coyuntura. Carta de Política Exterior Mexicana, 7(2). Fernández, A. M. (2008). Consular Affairs in the EU: Visa Policy as a Catalyst for Integration? The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 3(1), p. 21-35. https://doi.org/10.1163/187119008X266164 Fernández, A. M. (2009). Local consular cooperation: Administrating EU internal security abroad. European Foreign Affairs Review, 14(4), p. 591-606. Fernández Pasarín, A. M. (2010). La dimension externa del Espacio de Libertad, Seguridad y Justicia: el caso de la cooperación consular local. Revista CIDOB d’Afers Internacionals, núm. 91, p. 87-104. OPEN ACCESS (In Spanish). González Gutiérrez, C. (1998). Mexicans in the United States: An Incipient Diaspora. Voices of Mexico (43). OPEN ACCESS. Maftel, J. (2020). Application of the Principle of Mutual Consent in Consular Relations between States. Acta Universitatis Danubius, 16(2), p. 88-105. OPEN ACCESS. Melissen, J. (2020). Consular diplomacy's first challenge: Communicating assistance to nationals abroad. Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies, 7(2), p. 217-228. https://doi.org/10.1002/app5.298 OPEN ACCESS. Muro Ruiz, E. (2012). La diplomacia federativa de los gobiernos locales y los consulados mexicanos en Estados Unidos de América, en un multiculturalismo latino. Revista de la Facultad de Derecho de México, 60(254), p. 29-56. https://doi.org/10.22201/fder.24488933e.2010.254.30192 Potter, P. (1926). The Future of the Consular Office. American Political Science Review, 20(2), p. 284-298. Puente, J.I. (1930, January). The Nature of the Consular Establishment. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 78, p. 321-345. OPEN ACCESS. Romero Vara, L., Alfaro Muirhead, A.C., Hudson Frías, E., & Aguirre Azócar, D. (2021). Digital Diplomacy and COVID-19: An Exploratory Approximation towards Interaction and Consular Assistance on Twitter. Comunicación y Sociedad, e7960. https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2021.7960. OPEN ACCESS. Saliceti, A. I. (2011). The Protection of EU Citizens Abroad: Accountability, Rule of Law, Role of Consular and Diplomatic Services. European Public Law, 17(1), pp. 91-109. Schiavon, J. (2015). Consular Protection as State Policy to Protect Mexican and Central American Migrants. Central America-North America Migration Dialogue (CANAMID) Policy Brief #7. GOVERNMENT DOCUMENTS Acuerdo Interinstitucional entre los Ministerios de Relaciones Exteriores de los Estados Parte de la Alianza del Pacífico pare el Establecimiento de Medidas de Cooperación Consular en Materia de Asistencia Consular. (2014, February 10). (In Spanish). Agreement on Consular Assistance and Co-Operation between the Government of the Republic of Latvia, the Government of the Republic of Estonia and the Government of the Republic of Lithuania. (2019, December 6). Instituto Matías Romero (2018, October). Mexico and California’s Strategic Relationship: True Solidarity in Times of Adversity. Foreign Policy Brief 15. Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. Mendoza Yescas, J. & Sotres Brito, X. (2022, August). Acceptance of High-Security Consular Identification Card in Arizona: An Example of Consular Diplomacy. Foreign Policy Brief 21. Instituto Matías Romero. Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. BIBLIOGRAPHY LIST (04/23) BOOKS: Bada, X. & Gleeson, S. (eds.). (2019). Accountability Across Borders: Migrant Rights in North America. The University of Texas Press. Bada, X. & Gleeson, S. (2023). Scaling Migrant Worker Rights: How Advocates Collaborate and Contest State Power. The University of California Press. Especially chapter two: The Mexican Consular Network as an Advocacy Institution. OPEN ACCESS. Berridge, G.R. (2022). Diplomacy: Theory and Practice. 6th edition. Palgrave Macmillan and the DiploFoundation. Carrigan, W.D. and Webb, C. (2013). Forgotten Dead: Mob violence against Mexicans in the United States, 1848-1928. Oxford University Press. Casey, C. A. (2020). Nationals Abroad Globalization, Individual Rights, and the Making of Modern International Law. Cambridge University Press Délano Alonso, A. (2018). From here and there: Diaspora Policies, Integration, and Social Rights Beyond Borders. Oxford University Press. De Goey, F. (2014). Consuls and the Institutions of Global Capitalism. Routledge. Fernández de Castro, R, (coord.). (2018). La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump. El Colegio de la Frontera Norte & El Colegio de San Luis. (IN SPANISH) Gómez Arnau, R. (1990). México y la proteccion de sus nacionales en Estados Unidos. Centro de Investigaciones sobre Estados Unidos de América, UNAM. (IN SPANISH) Græger, N. and Leira, H. (eds.). (2020). The Duty of Care in International Relations: Protecting Citizens Beyond the Border. Routledge. Heinsen-Roach, E. (2019). Consuls and Captives: Dutch-North African Diplomacy in the Early Modern Mediterranean. University of Rochester Press. Hernández Joseph, D. (2015). Protección Consular Mexicana. Ford Foundation & Miguel Ángel Porrúa. (IN SPANISH) Herz, M. F. (1983). The Consular Dimension of Diplomacy: A Symposium. Institute of the Study of Diplomacy, Georgetown University. Hofstadter, C. G. (2020). Modern Consuls, Local Communities and Globalization. Palgrave Pivot. Lafleur, J.M. & Vintila, D. (2020). Migration and Social Protection in Europe and Beyond (Volume 2): Comparing Consular Services and Diaspora Policies. IMISCOE Research Series. OPEN ACCESS Melissen, J. (2005). The New Public Diplomacy: Between Theory and Practice. In J. Melissen (ed.), The New Public Diplomacy: Soft Power in International Relations. (pp. 3-27). Palgrave MacMillan. Melissen, J. and Fernandez, A. M., (eds.) (2011). Consular Affairs and Diplomacy. Martinus Nijhoff. Moyano Pahissa, Á. (1989). Antología Protección Consular a Mexicanos en los Estados Unidos 1849-1900.Archivo Histórico Diplomático Mexicano, Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. (IN SPANISH) Muñoz Martinez, M. (2018). The Injustice Never Leaves You: Ant-Mexican Violence in Texas. Harvard University Press. Platt, D. C. M. (1971). The Cinderella Service: British Consuls since 1825. Archon Books. BOOK CHAPTERS Berridge. G. R. (2022). Consulates. In G.R. Berridge, Diplomacy: Theory and Practice, (pp. 141-157). Palgrave and DiploFoundation. Calva Ruíz, V. (2018). Diplomacia Consular y acercamiento con socios estratégicos. In R. Fernández de Castro (coord.), La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, (pp. 205-216). El Colegio de la Frontera Norte & El Colegio de San Luis. (IN SPANISH) De Moya, M. & Bravo, V. (2021). Conclusion: Lessons Learned and Future Research. In V. Bravo & M. De Moya (eds), Latin American Diasporas in Public Diplomacy, (pp. 311-324). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74564-6_13 Fernández de Castro, R. & Hernández Hernández, A. (2018). Introducción. In R. Fernández de Castro(coord.), La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, (pp. 17-25). El Colegio de la Frontera Norte & El Colegio de San Luis. (IN SPANISH) Fernández Pasarin, A. M. (2016). Consulates and Consular Diplomacy. In C. Constantinou, P. Kerr & P. Sharp (eds.), The Sage Handbook of Diplomacy. Sage Publishing. Gómez Zapata, T. (2021). Civil Society as an Advocate of Mexicans and Latinos in the United States: The Chicago Case. In V. Bravo & M. De Moya (eds.), Latin American Diasporas in Public Diplomacy, (pp. 189-213). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74564-6_8 González Gutiérrez, C. (1997). Decentralized Diplomacy: The Role of Consular Offices in Mexico´s Relations with its Diaspora. In Rodolfo O de la Garza and Jesús Velasco (eds.), Bridging the Border: Transforming Mexico-U.S. Relations, (pp. 49-67). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. González Gutiérrez, C. (2006). Del acercamiento a la inclusión institucional: la experiencia del Insittuto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior. In C. Gónzalez Gutiérrez (coord.), Relaciones Estado-diáspora: aproximaciones desde cuatro continentes, Tomo 1, (pp. 181-220). Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. (IN SPANISH) González Gutiérrez, C. (2018). El significado de una relación especial: las relaciones de México con Texas a la luz de su experiencia en California. In R. Fernández de Castro (coord.), La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, (pp. 253-269). El Colegio de la Frontera Norte & El Colegio de San Luis. (IN SPANISH) Heijmans, M. y Melissen, J. (2007). MFAs and the Rising Challenge of Consular Affairs Cinderella in the Limelight. En K.S. Rana y J. Kurbalija (eds.), Foreign Ministries Managing Diplomatic Networks and Optimizing Value (pp. 192-206). Malta: DiploFoundation. Laveaga Rendón, R. (2018). Mantenerse a la Vanguardia: Desafío para los Consulados de México en Estados Unidos. In R. Fernández de Castro (coord.), La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, (pp. 231-251). El Colegio de la Frontera Norte & El Colegio de San Luis. (IN SPANISH) Leira, H. & Græger, N. (2020). Introduction: The Duty of Care in International Relations. In N. Græger & H. Leira (eds.), The Duty of Care in International Relations: Protecting Citizens Beyond the Border, (pp. 1-17). Routledge. Leira, H. & Neumann, I. B. (2011). The Many Past Lives of the Consul. In J. Melissen & A. M. Fernández, (eds.), Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, (pp. 223-246). Martinus Nijhoff. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004188761.i-334.69 Leira, H. & Neumann, I. B. (2017). Consular Diplomacy. In P. Kerr & G. Wiseman (eds.), Diplomacy in a globalizing world: Theories and Practice. 2nd edition. Oxford University Press. Melissen, J. (2011). Introduction The Consular Dimension of Diplomacy. In J. Melissen & A. M. Fernández, (eds.), Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, (pp. 1-17). Martinus Nijhoff. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004188761.i-334.6 Melissen, J. (2022). Consular Diplomacy in the Era of Growing Mobility. In Christian Lequesne (ed.), Ministries of Foreign Affairs in the World. Diplomatic Series, Vol. 18. (pp. 251-262). Brill Nijhoff. Mendoza Sánchez, J. C., & Cespedes Cantú, A. (2021). Innovating through Engagement: Mexico’s Model to Support Its Diaspora. In L. Kennedy (ed.), Routledge International Handbook of Diaspora Diplomacy. Routledge. Neumann, I. and Leira, H. (2020). The evolution of the consular institution. In I. Neumann, Diplomatic Tense,(pp. 8-25). Manchester University Press. Okano-Heijmans, M. (2011). Changes in Consular Assistance and the Emergence of Consular Diplomacy. In J. Melissen & A. M. Fernández, (eds.), Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, (pp. 21-41). Martinus Nijhoff. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004188761.i-334.13 Okano-Heijmans, M. (2013). Consular Affairs. In A. Cooper et al., (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Modern Diplomacy, (pp. 473-492). Oxford University Press. Rana, K. S. (2011). The New Consular Diplomacy. In K. S. Rana, 21st Century Diplomacy. A Practitioner's Guide. Continuum. Schiavon, J. A. & Ordorica R., G. (2018). Las sinergias con otras comunidades: el caso Tricamex. In R.Fernández de Castro (coord.), La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, (pp. 185-203). El Colegio de la Frontera Norte & El Colegio de San Luis. (IN SPANISH) Torres Mendivil, R. (2018). La diplomacia consular: un paradigma de la relación México-Estados Unidos. In R.Fernández de Castro (coord.), La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, (pp. 109-124). El Colegio de la Frontera Norte & El Colegio de San Luis. (IN SPANISH) Ulbert, J. (2011). A History of the French Consular Services. In J. Melissen & A. M. Fernández, (eds.),Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, (pp. 303-324). Martinus Nijhoff. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004188761.i-334.96 Valenzuela-Moreno, K. A. (2021). Transnational Social Protection and the Role of Countries of Origin: The Cases of Mexico, Guatemala, Bolivia, and Ecuador. In V. Bravo & M. De Moya (eds.), Latin American Diasporas in Public Diplomacy, (pp. 27-51). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74564-6_2 JOURNAL ARTICLES Bada, X., & Gleeson, S. (2015). A New Approach to Migrant Labor Rights Enforcement. Labor Studies Journal,40(1), 32-53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160449X14565112. Birka, I., Klavinš D., & Kits, R. (2022). Duty of Care: Consular Diplomacy Response of Baltic and Nordic Countries to COVID-19. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy, 17(2022), 1-32. https://doi.org/10.1163/1871191x-bja10115. Bravo, V., & De Moya, M. (2018). Mexico’s public diplomacy efforts to engage its diaspora across the border: Case study of the programs, messages and strategies employed by the Mexican Embassy in the United States. Rising Powers Quarterly, 3(3), 173-193. Cárdenas Suárez, H. (2019). La política consular en Estados Unidos: protección, documentación y vinculacion con las comunidades mexicanas en el exterior. Foro Internacional, LIX(3-4), 1077-1113. https://doi.org/10.24201/fi.v59i3-4.2652. (IN SPANISH) Crosbie, W. (2018). A Consular Code to Supplement the VCCR. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 13(2), 233-243. https://doi.org/10.1163/1871191X-11302019 Délano, A. (2009). From Limited to Active Engagement: Mexico’s Emigration Policies from a Foreign Policy Perspective. International Migration Review, 43(4), 764-814. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2009.00784.x. Délano, A. (2014). The diffusion of diaspora engagement policies: A Latin American agenda. Political Geography, 41, 90-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2013.11.007. De la Vega Wood, D. A. (2014). Diplomacia consular para el desarrollo humano: una visión desde la agenda democrática. Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior 101, May-August, 167-185. (IN SPANISH) Durand, J., Massey, D. S. & Parrado, E. A. (1999). The New Era of Mexican Migration to the United States. The Journal of American History, 86(2), 518-536. Gómez Maganda, G. and Kerber Palma, A. (2016). Atención con perspectiva de género para las comunidades mexicanas en el exterior. Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior, No. 107, May-August, 185-202. (IN SPANISH) González Gutiérrez, C. (1999). Fostering Identities: México´s Relations with Its Diaspora. The Journal of American History, 86(2), 545-567. https://doi.org/10.2307/2567045 Græger, N. & Lindgren, W. Y. (2018). The Duty of Care for Citizens Abroad: Security and Responsibility in the In Amenas and Fukushima Crises. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 13(2), 188-210. https://doi.org/10.1163/1871191X-11302009 Hernández Joseph, D. (2012). Mexico’s Concentration Consular Services. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy,7(2), 227-236. https://doi.org/10.1163/187119112X625556. Haugevic, K. (2018). Parental Child Abduction and the State: Identity, Diplomacy and the Duty of Care. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 13(2), 167-187. https://doi.org/10.1163/1871191X-11302010 Leira, H. (2018). Caring and Carers: Diplomatic Personnel and the Duty of Care. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 13(2), 147-166. https://doi.org/10.1163/1871191X-11302007 Leira, H. and de Carvalho, B. (2021). The Intercity Origins of Diplomacy: Consuls, Empires, and the Sea. Diplomatica 3 (1), 147-156. https://doi.org/10.1163/25891774-03010008 Lottaz, P. (2020). Going East: Switzerland´s east consular diplomacy toward East and Southeast Asia. Traverse: Zeitschrift für Geschichte = Revue d´historie 27(1), 23-34. Marina Valle, V., Gandoy Vázquez, W. L., and Valenzuela Moreno, K. A. (2020). Ventanillas de Salud: Defeating challenges in healthcare access for Mexican immigrants in the United States. Estudios Fronterizos, 21 (e043). https://doi.org/10.1080/23340460.2020.1714462 Márquez Lartigue, R. (2023). Beyond Traditional Boundaries: The Origins and Features of the Public-Consular Diplomacy of Mexico. Journal of Public Diplomacy 2(2), 48-68. Martínez-Schuldt, R. D. (2020). Mexican Consular Protection Services across the United States: How Local Social, Economic, and Political Conditions Structure the Sociolegal Support of Emigrants. International Migration Review, 54(4), 1016-1044. Melissen, J. (2020). Consular diplomacy's first challenge: Communicating assistance to nationals abroad. Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies, 7(2), 217-228. https://doi.org/10.1002/app5.298 Melissen, J. & Okano-Heijmans, M. (2018). Introduction. Diplomacy and the Duty of Care. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 13(2), 137-145. https://doi.org/10.1163/1871191X-23032072 Navarro Bernachi, A. (2014). La perspectiva transversal y multilateral de la protección consular. Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior (101), May-August, 81-97. (IN SPANISH) Necochea López, R. (2018). Mexico´s health diplomacy and the Ventanilla de Salud program. Latino Studies(16), 482-502. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41276-018-0145-8 Okano-Heijmans, M. & Price, C. (2019). Providing consular services to low-skilled migrant workers: partnerships that care. Global Affairs, 5(4-5) 427-443. https://doi.org/10.1080/23340460.2020.1714462 Rangel Gomez, M. G., Tonda, J., Zapata, G. R., Flynn, M., Gany, F., Lara, J., Shapiro, I, & Ballesteros Rosales, C. (2017). Ventanillas de Salud: A Collaborative and Binational Health Access and Preventive Care Program. Frontiers in Public Health 5. 30 June. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00151. Schiavon, J. A. & Cárdenas Alaminos, N. (2014). La proteccón consular de la diáspora mexicana. Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior (101), May-August, 43-67. (IN SPANISH) Torres Mendivil, R. (2014). Morfología, tradición y futuro de la práctica consular mexicana. Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior 101, May-August, 69-79. (IN SPANISH) Tsinovoi, A. and Adler-Nissen, R. (2018) Inversion of the “Duty of Care”: Diplomacy and the protection of Citizens Abroad, from Pastoral Care to neoliberal Governmentality. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy (13) 2, 211-232. https://doi.org/10.1163/1871191X-11302017 Xia, L. (2021). Consular Protection with Chinese Characteristics: Challenges and Solutions. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 16 (2-3), 253-274. https://doi.org/10.1163/1871191X-BJA10068. Valenzuela-Moreno, K. (2019). Los consulados mexicanos en Estados Unidos: Una aproximación desde la protección social. INTERdisciplina, 7(18), 59-79. https://www.revistas.unam.mx/index.php/inter/article/view/68460/61387. OTHER WORKS Batalova, J. (2008). Mexican Immigrants in the United States. Migration Policy Institute. 23 April. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/mexican-immigrants-united-states-2006. Bruno, A. y Storrs, K. L. (2005). Consular Identification Cards: Domestic and Foreign Policy Implications, the Mexican Case, and Related Legislation. Congressional Research Services. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/RL32094.pdf. Global Consular Forum. (2016). Seoul Consensus Statement on Consular Cooperation, 27 October. González, C., Martínez, A. & Purcell, J. (2015). Report: Global Consular Forum 2015, Wilton Park, July. Global Consular Forum. Haynal, G., et al. (2013). The Consular Function in the 21st Century: A report for Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada. Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto. Israel, E. & Batalova, J. (2020). Mexican Immigrants in the United States. Migration Policy Institute. 5 November. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/mexican-immigrants-united-states-2019. Kunz, R. (2008). Mobilising diasporas: A governmentality analysis of the case of Mexico. Working Paper Series, “Glocal Governance and Democracy” 3. Institute of Political Science, University of Lucerne. https://zenodo.org/record/48764?ln=en#.YyZZyC2xBaR. Laglagaron, L. (2010). Protection through Integration: The Mexican Government’s Efforts to Aid Migrants in the United States. Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/IME_FINAL.pdf Márquez Lartigue, R. (2021). El surgimiento de la Diplomacia Consular: su interpretación desde México. Unpublished essay. (IN SPANISH) Murray, L. (2013). Conference report: Contemporary consular practice trends and challenges, Wilton Park, October. Global Consular Forum. Noe-Bustamante, L., Flores, A. & Shah, S. (2019). Facts on Hispanics of Mexican origin in the United States, 2017. Pew Hispanic Center. 16 September. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/fact-sheet/u-s-hispanics-facts-on-mexican-origin-latinos/. GOVERNMENT DOCUMENTS Global Affairs Canada. (2017). Evaluation of the Consular Affairs Program. Diplomacy, Trade and Corporate Evaluation Division, Global Affairs Canada. https://www.international.gc.ca/gac-amc/assets/pdfs/publications/evaluation/2018/cap-pac-eng.pdf Gradilone, E. (2012). Diplomacia Consular 2007 a 2012. Ministério das Relações Exteriores (Brazil) and Fundação Alexandre de Gusmão. https://funag.gov.br/biblioteca-nova/produto/1-182-diplomacia_consular_2007_a_2012 Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior. (2018). Población Mexicana en el Mundo: Estadística de la población mexicana en el mundo 2017. 23 July.http://www.ime.gob.mx/estadisticas/mundo/estadistica_poblacion_pruebas.html. Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior. (2021). ‘Revista “Casa de México”’. 22 January. https://www.gob.mx/ime/articulos/revista-casa-de-mexico. Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. (2019). Fortalecimiento de la Atención a Mexicanos en el Exterior, Libro Blanco 2012-2018. (IN SPANISH) OTHER BLOG POSTS (BESIDES THIS BLOG) Márquez Lartigue, R. (2021). Public-Consular Diplomacy at its Best: The case of the Mexican Consular ID card program. CPD Blog. 4 February. https://uscpublicdiplomacy.org/blog/public-consular-diplomacy-its-best-case-mexican-consular-id-card-program. Márquez Lartigue, R. (2021). Public-Consular Diplomacy That Works: Mexico’s Labor Rights Week in the U.S. CPD Blog. 6 October. https://uscpublicdiplomacy.org/blog/public-consular-diplomacy-works-mexicos-labor-rights-week-us. Márquez Lartigue, R. (2022). Public-Consular Diplomacy That Heals: Binational Health Week Program. CPD Blog. 8 June. https://uscpublicdiplomacy.org/blog/public-consular-diplomacy-heals-binational-health-week-program. Manor, I. (2022, January 25). Are Consular Tweets a New Form of Crisis Signaling? Exploring Digital Diplomacy blog. https://digdipblog.com/2022/01/25/are-consular-tweets-a-new-form-of-crisis-signaling/ DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer, or company.

0 Comments

This post is dedicated to all individuals and institutions participating in the IME's activities and programs through its 20-year history. On Sunday, April 16, the Institute of Mexicans Abroad (Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior) celebrated its 20th anniversary. On that day in 2003, the government of Mexico published the Decreet that established this new diaspora engagement institution in the Federal Registry. The Institute, also known as the IME (for its acronym in Spanish), revolutionized the relationships between the government of Mexico (especially the executive branch of the federal government) and the Mexican community in the United States and Canada. For the first time in history, Mexican migrants and second-generation and National Hispanic organizations sat at the table by participating in the IME's Advisory Council (known as the Consejo Consultivo del IME or CCIME). The IME also profoundly transmuted the role of the consulates and hometown associations in their host municipalities and states, engaging with a wide variety of actors from businesses and local authorities to civil society organizations and institutions. They developed effective and long-lasting partnerships to cater to the needs of the Mexican community in North America. Their activities can be classified as a successful public diplomacy effort (Márquez Lartigue, 2023). Background Even though migration to the United States has been a constant in some states in Mexico for over a century, significant changes dramatically transformed the situation in the late 1980s and through the 1990s. The combination of several factors metamorphosed Mexican migrants from temporary workers into a permanent diaspora:

Besides, the government of Mexico reformed its consular system, including the establishment of the Program of Mexican Communities Abroad in 1990, expanded its consular network, and granted greater autonomy to consular officers to actively engage with Mexican community leaders, local and state authorities, and civil society organizations (González Gutiérrez, 1997). Government officials encouraged the establishment of Hometown Associations and confederations among migrants and Migrants Care Offices (Oficinas de Atención a Migrantes) by Mexican provincial and even municipal authorities. After the failure to negotiate a migration accord with the U.S. in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, the government of Mexico created the National Council for Mexican Communities Abroad in the summer of 2002. One of the council's tasks was to receive recommendations from consultative mechanisms (Diario Oficial de la Federación, 2002). The establishment of the IME In the autumn of 2002, Mexican consulates across the United States and Canada invited migrant community leaders to participate in the selection process of an advisory board that was going to be established as part of the IME. Ayón (2006) explains that the IME was added to traditional consular programs such as documentary services (passports, notary public, and visas) and assistance to distressed citizens because the Institute could "plan, handle, propose, and pursue national and binational strategic goals and respond to the challenges that transcend the consular district" (p. 132). IME's first Executive Director indicated that the institute had three primary functions: information dissemination, empowerment of the communities, and provision of innovative new services that go beyond regular consular programs (González Gutiérrez, 2009). Regarding information distribution, the IME had three major programs:

The consular network began offering social services through partnerships with non-governmental organizations, authorities, and even businesses. These services centered on non-traditional areas such as education (Plazas Comunitarias -Basic Adult Education- program, scholarships -IME Becas-, and exchange of teachers, among others), health (centered around the Ventanillas de Salud or Health Desks and the Binational Health Week); financial education and investment of remittances (Financial Advisory Desk -Ventanilla de Asesoría Financiera-, the Three-for-one program, and Directo a Mexico. The most important task was the empowerment of the Mexican community through the CCIME and participation in the information and services agendas (Ayón 2006, p. 132). In many ways, the government of Mexico, through its consular network, was already working on most of these programs before the creation of the IME. Notwithstanding, the key innovative aspect of the institute was its advisory council. For the first time, its approximately 120 members from across the U.S. and Canada gathered at least twice a year to prepare recommendations about policies directed at Mexican migrants in North America. The first director of the Institute, Don Cándido Morales, was also a migrant from Oaxaca living In California. Even though the CCIME had limited responsibilities centered on presenting non-binding recommendations, it provided a national platform for migrant leaders. On the one hand, they meet and engage each other, strengthening their advocacy and organization skills. It was an executive leadership training academy (Ayón, 2006, p. 135). On the other hand, it opened the doors to authorities on both sides of the border at all levels. It facilitated their engagement with civil society and, for some, in political activities. Giving Mexican migrants a voice and visibility through the CCIME was helpful as it helped expand many of the IME programs, such as the Health Desks and the creation of IME Becas. Also, many board members advocated enacting the overseas absentee vote implementing law in 2005 and the migrant demonstrations of the Spring of 2006. The IME has evolved thought its 20 years of existence, but most of its core functions continue to this day. In 2022, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs launched the 2022-2024 Action Plan for Mexicans living overseas, which contains nearly 40 activities. IME's successful public diplomacy Without using the term public diplomacy, the IME's activities can be defined as such. Its programs encompass Professor Nicholas Cull's (2019) five elements of public diplomacy listening, advocacy, cultural activities, and educational exchanges. Even there was some international broadcasting in the form of electronic information bulletins. Interestingly, the target audiences were migrants themselves. However, it did not stop there; through its many undertakings, consular offices engaged with all sorts of people and organizations and slowly built long-lasting partnerships. Thus, nowadays, the IME "has about 2,000 partners in Mexico and the USA" (Mendoza Sánchez & Cespedes Cantú, 2021). Another contribution of the IME was that many countries, from Uruguay to Morocco and Türkiye to Colombia, requested meetings and attended some of its activities to learn more about the country's diaspora engagement programs. (Laglagaron, 2010, p. 39; Délano, 2014). The IME generated soft power for Mexico's diplomacy soft power, as it attracted attention around the globe. It has also generated consular partnerships with other Latin American consulates in programs like Binational Health Week and Labor Rights Week that are celebrated across the U.S. every year. With the countries of the Northern Triangle of Central America, several consulates established consular coordination schemes known as Tricamex. One of the most outstanding achievements of the IME was reducing the barriers between the government and the migrants. After years of hard work, little by little, it has gained the community's trust, which was very little. Significant investments in the modernization of documentary services have also resulted in better quality services. The Institute also gave way to the rise of Mexico's public-consular diplomacy. To learn more about its origins and features, read my practitioner's essay in the Journal of Public Diplomacy titled Beyond Traditional Boundaries: The Origins and Features of the Public-Consular Diplomacy of Mexico. References Ayón, D.R. (2006). La política mexicana y la movilización de los migrantes en Estdos Unidos. In Carlos Gónzalez Gutiérrez (coor.), Relaciones Estado-diáspora: La perspectiva de América Latina y el Caribe. Tomo II, (pp. 113-144). Ciudad de México. Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. Cull, N. J. (2019). Public Diplomacy: Foundations for Global Engagement in the Digital Age. (Kindle Edition). Délano, A. (2014). The diffusion of diaspora engagement policies: A Latin American agenda. Political Geography, 41, 90-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2013.11.007. Diario Oficial de la Federación. (2002, August 8). Acuerdo por el que se crea el Consejo Nacional para las Comunidades Mexicanas en el Exterior. https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=721574&fecha=08/08/2002#gsc.tab=0 Diario Oficial de la Federación. (2003, April 16). Decreto por el que se crea el Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior, con el carácter de órgano administrativo desconcentrado de la Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. https://www.gob.mx/ime/documentos/decreto-por-el-que-se-crea-el-ime González Gutiérrez, C. (1997). Decentralized Diplomacy: The Role of Consular Offices in Mexico´s Relations with its Diaspora. In Rodolfo O de la Garza and Jesús Velasco (eds.), Bridging the Border: Transforming Mexico-U.S. Relations, (pp. 49-67). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. González Gutiérrez, C. (2006). Introduccion: El papel de los gobiernos. In Carlos Gónzalez Gutiérrez (coor.), Relaciones Estado-diáspora: La perspectiva de América Latina y el Caribe. Tomo II, (pp. 13-42). Ciudad de México. Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. González Gutiérrez, C. (2009). The Institute of Mexicans Abroad: An Effort to Empower the Diaspora. In Dovelyn Rannverg Agunias (ed.), Closing the Distance: How Governments Strengthen ties with their Diasporas, (pp. 87-98). Washington, DC. Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/closing-distance-how-governments-strengthen-ties-their-diasporas Laglagaron, L. (2010). Protection through Integration: The Mexican Government's Efforts to Aid Migrants in the United States. Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/IME_FINAL.pdf Márquez Lartigue, R. (2023). Engaging migrants in the Mexico-US diplomatic relationship: The Institute of Mexicans Abroad. Working paper presented in the ISA 2023 convention. Unpublished. Mendoza Sánchez, J. C., & Cespedes Cantú, A. (2021). Innovating through Engagement: Mexico’s Model to Support Its Diaspora. In L. Kennedy (ed), Routledge International Handbook of Diaspora Diplomacy (Kindle Edition). Routledge. Terrazas, A. and Papademetriou, D. G. (2010). Reflexiones sobre el compromiso de México con Estados Unidos en materia de migración con énfasis en los programas para la comunidad de mexicanos en el exterior. In Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores, Mexicanos en el Exterior: Trayectorias y Perspectivas (1990-2010), (pp. 107-139). Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores, Instituto Matías Romero. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company.  Following up on my previous post, “Recent studies on consular diplomacy: reevaluating the consular institution,” about recent works on consular diplomacy, I want to share two great articles I just finished reading. But first, I want to share that the Journal of Public Diplomacy recently published my practitioner's essay titled Beyond Traditional Boundaries: The Origins and Features of the Public-Consular Diplomacy of Mexico. It is open access, so I invite you to read it too. The first article I just read is titled “Duty of Care: Consular Diplomacy Response on Baltic and Nordic Countries to COVID-19”, and was published by the Hague Journal of Diplomacy (open source article).[i] The second is “Going East: Switzerland´s east consular diplomacy toward East and Southeast Asia”, written by Pascal Lottaz and focuses on opening Swiss consular offices in the Far East in the 1860s. So, let´s start with the comparative study of the Baltic and Nordic countries´ consular diplomacy in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. “Duty of Care: Consular Diplomacy Response on Baltic and Nordic Countries to COVID-19” The article is a must-read for anybody interested in the latest developments in diplomatic practices. It includes discussions on the evolution from consular services into consular diplomacy through the expansion into foreign policy, digital diplomacy, and citizen-centric initiatives.[ii] There are few comparative studies of consular diplomacy; therefore, this essay is very much welcomed. It also showcases the different responses to the biggest-ever challenge for consular assistance, as the pandemic was once in a millennia occurrence that closed down the entire world. Birka, Klavinš, and Kits explain the concept of “Duty of Care” and the importance of the state–society relationship in implementing consular assistance to citizens abroad in the real world. They classify this responsibility into two categories the “pastoral care concept [in] which citizens are objects to be protected [and the] neoliberal governmentality conception where citizens are expected to take on more responsibility for their own well-being.”[iii] The authors define the concept “as the assistance and protection of citizens through guidance and information provision, enabling citizens to make informed decisions and care for themselves. However, when faced with the pandemic, all states made minor adjustments to this approach and assumed some level of a pastoral DoC role by exceeding normal consular services provision.”[iv] Birka, Klavinš, and Kits also discuss the changes in consular affairs, particularly the refocusing of ministries of foreign affairs into a greater engagement with its citizens and the inclusion of new diplomatic tools such as digital and diaspora diplomacies into their primary functions. The rise of consular diplomacy is part of these transformations and was put to a big test with the COVID-19 pandemic. The evaluation and comparison of the response of the Nordic and Baltic countries to the pandemic is a significant contribution to the field of consular diplomacy studies. Despite their similarities, the eight countries have essential differences in their consular emergency responses. The categorization of the countries' consular responses to the pandemic, reflected in tables 2 ”extent of pastoral care provided”[v] and 3 “aspects of consular diplomacy,”[vi] could be applied in other comparative or single-country case studies. A key highlight of “Duty of Care: Consular Diplomacy Response on Baltic and Nordic Countries to COVID-19”, is the importance of having robust relationships among different MFAs to be able to evolve from consular coordination schemes to full-fledged consular diplomacy, which happened among the Nordic states but not in the Baltic region. Regarding innovative approaches, Lithuania and Denmark stand out. By using their established connections with their diasporas, the two countries were able to mobilize them to assist their nationals in the first months of the pandemic.[viii] Citizens' active participation in helping governments distribute valuable information and their assistance to some people showcases the new role of citizens in diplomacy and consular assistance. The study underscores the significant contributions of information and communications technologies to diplomacy. Having a smartphone application with hundreds of thousands of users and being able to send SMS messages to all citizens abroad underline their vital role in today´s consular diplomacy. Even traditional MFAs webpages were crucial in disseminating information to people stuck overseas and their family members in the home country. Birka, Klavinš, and Kits successfully explain the critical elements of today´s consular diplomacy, and I am sure their comparative study will be highly cited work in the field. It is a must-read for everybody interested in today´s diplomacy, not only consular affairs. Now, let´s move on to the historical essay on Switzerland's consular diplomacy in the late 19th century. “Going East: Switzerland´s east consular diplomacy toward East and Southeast Asia” From the onset, it is hard to imagine why a small land-locked country like Switzerland would be interested in opening consulates in Asia. However, after reading the article, it all makes sense; therefore, this essay is also a valuable contribution to the field of consular diplomacy. It is fascinating to learn about how trade interests pushed the opening of Swiss consulates in Manila (1862), Batavia (now Jakarta) in 1863, and Yokohama and Nagasaki (Japan) a year later. Back then, the Alps´ nation had only three embassies -Paris, Vienna, and Turin (its three big neighbors)- but had 77 honorary consulates; therefore, most of its foreign activities were conducted by non-official consular officers rather than state diplomats.[ix] “Going East: Switzerland´s east consular diplomacy toward East and Southeast Asia” showcases the linkage between colonial powers and small European countries in their trade expansion two centuries ago. Switzerland was able to open two new consulates with the assistance of Spain and the Netherlands. Besides, the U.S. and the Dutch helped Swiss diplomats sign a friendship treaty with Japan in 1864 after a failed attempt.[x] Lottaz identifies the need for new markets for Swiss manufactured goods as the main objective in expanding relations with the Far East, which was driven mainly by a few tycoons, also called “Federal Barons.”[xi] He also ascertains that the expansion resulted from “the opportunity structure of the colonial era.”[xii] Another issue that surfaced in this research was the concern about giving an advantage to a company with the designation of honorary consul abroad, issue that later was overturned, as the Swiss government designated the same person the second time around.[xiii] This subject still matters today, as demonstrated by the recent investigation into honorary consuls´ criminal activities and nefarious behaviors (See below). Here are some topics that came up in the conclusions of the article which could be further studied:

The article reinforces the idea that most of the consular activities in the 19th century were focused on protecting trade interests, which were part of the national interest, rather than individual citizens. This perspective differs in the case of Mexico, which early on focused on protecting citizens in distress in the U.S. that had no trade connections. “Going East: Switzerland´s east consular diplomacy toward East and Southeast Asia” is a worthwhile contribution to understanding the links between trade and diplomacy and the merging of consular and diplomatic functions into what is known today as consular diplomacy. A brief comment on Consuls and Captives: Dutch-North African Diplomacy in the Early Modern Mediterranean Before finishing, I just want to briefly comment on the book Consuls and Captives: Dutch-North African Diplomacy in the Early Modern Mediterranean by Erica Heinsen-Roach. It is not new, but it is fascinating historical research that demonstrates that diplomacy is not a uniquely European creation. The fact is that for nearly 300 hundred years, Maghribi corsairs and rulers in Morocco, Algiers, and Tunis, were able to deal on their own terms with European powers, mainly under the title of consuls, who performed diplomatic duties. The book has a human dimension as it centers on the adventurous lives of Dutch consuls and a couple of non-resident ambassadors stationed on the African shores of the Mediterranean Sea. It provides an excellent example of the role of consuls in diplomacy. One of the defining elements of consular diplomacy is high-visibility consular cases[xiv]; therefore, what is more relevant than the enslavement of Dutch nationals in the Mediterranean and the government’s efforts to release them? As seen in the Swiss expansion to Asia, in this case, consular protection of citizens in distress was mainly related to trade interests, as the corsairs’ seizure of Dutch vessels and citizens in the Mediterranean affected the national interests. However, it seems that there is also a humanitarian responsibility, described as “duty of care” by the Dutch authorities, to look after its nationals abroad, particularly in these situations where the government's action made the difference between freedom and slavery. A final note on the honorary consuls’ global investigation. Recently, ProPublica and the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists launched a global investigation on honorary consuls titled “Shadow diplomats: The Global Threat of Rogue Diplomacy.” This study is unique as consular affairs are typically covered by the media on crises or high-visibility consular cases, not the consular officials´ performance and activities. Sadly, it focuses on the “rogue” side rather than honorary consuls´ substantial contributions, especially in assisting distressed citizens abroad and promoting greater ties between nations. Most of the cases described in the research would still exist, as honorary consular usually are citizens of the host country rather than foreigners. The only, and important difference is their status as consular officers granted by both the receiving and the sending governments´. Of course, any criminal activity should be prosecuted, and abuses should be reported and sanctioned. [i] Birka, I., Klavinš D., & Kits, R. (2022). Duty of Care: Consular Diplomacy Response of Baltic and Nordic Countries to COVID-19. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy, 17(2022), 1-32. [ii] Birka, I., Klavinš D., & Kits, R. (2022). [iii] Tsinovoi A. and Adler-Nissen, R. (2018) Inversion of the “Duty of Care”: Diplomacy and the protection of Citizens Abroad, from Pastoral Care to neoliberal Governmentality. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy (13) 2, cited in Birka, I., Klavinš D., & Kits, R. (2022). p. 7. [iv] Birka, I., Klavinš D., & Kits, R. (2022). p. 26. [v] Birka, I., Klavinš D., & Kits, R. (2022). p. 16. [vi] Birka, I., Klavinš D., & Kits, R. (2022). pp. 23-24. [vii] Birka, I., Klavinš D., & Kits, R. (2022). pp. 22-24. [viii] Birka, I., Klavinš D., & Kits, R. (2022). pp. 22-24. [ix] Lottaz, P. (2020). Going East: Switzerland´s east consular diplomacy toward East and Southeast Asia. Traverse: Zeitschrift für Geschichte = Revue d´historie 27(1), p. 23-24. [x] Lottaz, P. (2020). p. 28. [xi] Lottaz, P. (2020). pp. 25-26. [xii] Lottaz, P. (2020). p. 24. [xiii] Lottaz, P. (2020). pp. 24 and 30. [xiv] See Maaike Okano-Heijmans. (2011). Changes in Consular Assistance and the Emergence of Consular Diplomacy. In Jan Melissen and Ana Mar Fernandez (eds.) Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, pp. 21-41. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed here are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer, or company.  This blog post is dedicated to all the Mexican diplomats and U.S. legal teams that work with death penalty cases involving Mexicans, especially in memoriam of Imanol de la Flor Patiño, an exemplary person. Today, twenty years ago, Mexico sued the United States in the International Court of Justice for violations of the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations (VCCR), specifically Article 36, which provides the right of consular notification to foreign citizens detained abroad. The case concerning Avena and other Mexican nationals against the United States was a milestone in Mexico's assistance to its citizen overseas, particularly in the United States. In March 2004, the Court rendered its judgment against the United States, thus becoming an instrumental decision for the consular protection of the rights of Mexicans arrested north of the border and also for the 52 named cases (Gómez Robledo 2005, p. 183). The Avena case is Mexico's most consequential consular protection case because it overhauled the assistance consulates provide to distressed citizens and raised the relevance of consular affairs inside the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Background In 1976, the United States Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty. In 1993, a Mexican was executed in Texas; he was the first Mexican put to death after the reimposition of capital punishment. His execution was a big issue in Mexico which generated "more than a hundred condemnatory articles in the [Mexican] press, and pronouncements by not only the minister of Foreign Affairs but the President [of Mexico]" (González de Cossío, 1995, p. 102). As a result, Mexico took a series of actions that helped prepare for the presentation of the Avena case in 2003. One immediate step was to interview all Mexicans on death row. As part of the process, consular officials identified a systemic violation of the right to consular notification in capital cases (González Félix, 2009, p. 218-220). In addition, in 1997, Mexico asked the Inter-American Court of Human Rights for an Advisory Opinion (OC-16/99) about the consular notification. It was a multilateral effort and was not bidding; thus, it was not a direct confrontation with the U.S. The Court published its opinion in 1999, stating that foreign individuals have certain rights under the VCCR, such as the rights of information, consular notification, and communications. Besides, it determined that the sending state and its consular officers also have the right to communicate with its detained nationals (Cárdenas Aravena, n.d). In 2000, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Mexico launched a new program to assist Mexicans on death row in the United States. This program complemented the legal training that some Mexican diplomats received as part of the official collaboration with the University of Houston that started in 1989 (see, for example, De la Flor Patiño, 2017 and number 109 of the Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior). Enhancing consular protection With the arrival of President Fox in 2000, Mexico's government stepped up its engagement with the Mexican community in the United States intending to enhance consular protection. Mexico started negotiating a bilateral migration agreement with the recently inaugurated U.S. president, George W. Bush. The government established the Presidential Office for Migrants Abroad, promoted the Mexican Consular ID Card, and created and expanded consular programs such as the Binational Health Week and the Ventanilla de Salud (Health Desk). In early 2002, the country ratified the Optional Protocol concerning the Compulsory Settlement of Disputes of the VCCR, to which the United States was also a party (González Félix, 2009, p. 221-222), thus offering a binding conflict resolution mechanisms. Meanwhile, the number of Mexicans sentenced to death and executed by U.S. authorities increased, creating an uproar in Mexico. In January 1995, there were 23 Mexicans sentenced to death in the U.S. (González de Cossío, 1995, p. 108). The ICJ's Avena Judgment decision of 2004 included 51 cases. From 1997 to 2002, four nationals were put to death in Texas and Virginia (Death Penalty Information Center, n/d). Even President Fox suspended a trip to president's Bush ranch in Texas in August 2002 as a protest of the execution of a Mexican in the same state (Gómez Robledo 2005, p. 178-179). Meanwhile, Paraguay in 1998 and Germany in 1999 requested the intervention of the ICJ regarding the Breard and LaGrand cases related to violations of consular notification rights by U.S. authorities. In Paraguay's case, the proceedings were stopped after the execution of its national in 1998, while the German brother's case continued even after both were put to death in 1999. Both instances were significant for Mexico's consular protection of its nationals on death row. According to Gómez Robledo (2005), after LaGrand's ICJ decision in June 2001, Mexico tried to work with the United States regarding the Mexicans sentenced to death whose rights were violated by local authorities by denying the consular access with no avail (p. 178-179). The Avena Judgment and its repercussions In January of 2003, in a bold action, Mexico presented in the ICJ the Avena case against the United States for violations of Article 36 of the VCCR regarding the death penalty cases of 54 Mexicans in the United States (Covarrubias Velasco, 2010, p. 133-134). The case had significant implications and had very high visibility in Mexico, particularly at a time when the migration to the United States grew very fast, passing from 4.3 million in 1990 to 9.1 million in 2000 (Rosenbloom & Batalova, 2022). After more than a year, which included one provisional measure, on March 31, 2004, the ICJ issued its judgment. In summary, "the ICJ concluded that the United States had violated its obligations under the Vienna Convention [on Consular Relations] by failing to properly notify Mexican nationals of their rights to have Mexican consular officials notified of their arrest, which in turn deprived Mexican consular officers of their right under Article 36 to render assistant to their detained nationals "(Garcia, 2004, p. 14). More significantly, "the Court ordered the United States to provide judicial review to each and every one of the fifty-one Mexicans named in the suit whose Article 36 rights had been violated, and to determine whether the failure to timely advise the consulate of their arrests resulted in "actual prejudice to the defendant." Importantly, the United States judiciary also had to review and reconsider the convictions and sentences as if the procedural default did not exist" (Kuykendall and Knight, 2018, p. 808-809). It was a massive victory for the rights of the Mexicans on death row, as it was mandatory for the U.S. government. The Judgment bound the U.S. to the 51 Mexicans with capital sentences, regardless of the eventual outcome of each case. The Avena case was a milestone for Mexico's consular protection because:

However, not all has been good news. Regarding the demand by the ICJ court that the U.S. review and reconsider the cases of the 51 Mexicans named in the Avena Judgment, the federal government has faced internal challenges. The most important of these was the Supreme Court's decision regarding the case of Medellin vs. Texas (p. 491). In 2008, the Court indicated that the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations is not a self-execution treaty, therefore, the U.S. Congress must legislate so it could become part of the U.S. law (Medellin vs. Texas (p. 491-492). Regardless of U.S. authorities' continuous breach of their international obligations, there have been crucial domestic adjustments. In some cases, State courts decided to review the death penalty cases based on the Avena Judgment and provided relief to Mexicans on death row. In addition, some states "have at least some statutory requirements concerning consular notification…[and] beginning in December 2014, the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedures now provide that at an initial appearance, the judge must inform the defendant" (Kuykendall and Knight, 2018, p. 824) that if they are foreigners, they have the right to contact their consulates. Besides, since the start of the Avena case in 2003, the support for the death penalty in the U.S. has been declining ever so slowly. In conclusion, the Avena case was Mexico's most consequential consular protection case, which enormously influenced the emergence of the country's public-consular diplomacy. References Cárdenas Aravena, C. (n.d). La Opinión Consultiva 16/99 de la Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos y la Convención de Viena de Relaciones Consulares. Covarrubias Velasco, A. (2010). Cambio de siglo: la política exterior de la apertura económica y política. México y el mundo: Historia de sus relaciones exteriores. Tomo IX. El Colegio de México. Death Penalty Information Center, n.d. Execution of Foreign Nationals [in the United States. De la Flor Patiño, I. (2017). Pena de muerte en el condado de Harris, una mirada a través del cristal de la Universidad de Houston. Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior (109), 99-123. Gallardo Negrete, F. (2022, April 27). La pena de muerte en México, una historia constitucional. Este País. Garcia, M. J. (2004, May 17). Vienna Convention on Consular Relations: Overview of U.S. Implementation and International Court of Justice (ICJ) Interpretation of Consular Notification Requirements. Congressional Research Service. Gómez Robledo V., J. M. (2005). El caso Avena y otros nacionales mexicanos (México c. Estados Unidos de América) ante la Corte Internacional de Justicia. Anuario Mexicano de Derecho Internacional Vol. V, 173-220. https://revistas.juridicas.unam.mx/index.php/derecho-internacional/article/view/119/177 González Félix, M. A. (2009). Entrevistas: Pasajes Decisivos de la Diplomacia. El Caso Avena. Interview by C. M. Toro. Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior (86), 215-223. June. González de Cossío, F. (1995). Los mexicanos condenados a la pena de muerte en Estados Unidos: la labor de los consulados de México. Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior (46) 102-125. Spring. Kuykendall, G. & Knight, A. (2018). The Impact of Article 36 Violations on Mexicans in Capital Cases. Saint Louis University Law Journal 62(4), 805-824. Rosenbloom, R. & Batalova, J. (2022, Oct. 13). Mexican Immigrants in the United States. Migration Policy Institute. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company. I am extremely happy to share with you the article Beyond Traditional Boundaries: The Origins and Features of the Public-Consular Diplomacy of Mexico, published in the newest edition of the Journal of Public Diplomacy. You can read it or download it in this link: https://www.journalofpd.com/_files/ugd/75feb6_82201616bab74db6b1f877c8deb734d6.pdf Besides, if you are interested in the origins of Mexico's consular diplomacy, you can read my previous post here. You can also read additional posts about consular diplomacy, such as:

DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company. Maribel (not her real name) went with her family to a Mexican consulate in the U.S. She was there to get a health referral to have a free mammogram at the local health clinic. Besides, her youngest kid, Jaime, needed eyeglasses, so she got a voucher for free prescription glasses from a well-known grocery store. On the same visit, Eduardo, a Guatemalan citizen and Maribel's partner received screenings for blood glucose and blood pressure. All these services were provided by the Ventanilla de Salud program (VDS -Health Desk/Window-)[i], a public-consular diplomacy effort that will celebrate its 20th anniversary next year. Since its creation as a pilot program in Southern California in 2003, the VDS at the Mexican consulates (and mobile units) has provided more than 45.8 million health-related services to 18.3 million people. Its services are not exclusively for Mexicans, so many more people, including U.S. citizens, have benefited from this effort. The VDS does not solve all the health-related barriers and issues faced by the Mexican migrants in the U.S.; however, it certainly alleviates some of their anguish and distress. Background. The primary motivation behind establishing the VDS is the unequal access to health services in the U.S. by Hispanics in general and undocumented migrants in particular, even after the enactment of the Affordable Care Act of 2010. In 2016, 24 million persons did not have health insurance, and the percentage of Hispanics uninsured of the total grew from 29% in 2013 to 40%. In 2019, two out of five Mexican migrants did not have insurance (38%), “compared to 20% of all immigrants and 8% of the U.S. born.”[ii] Two years later, the percentage of uninsured Mexican migrants diminished by 1% to reach 37% in 2021.[iii] In the United States, an uninsured person typically pays full price for medical expenses, while an insured individual will receive negotiated discounts from their insurance, so the cost drops dramatically. The passing of Proposition 187 in California in 1994 significantly impacted the Hispanic community, not only the undocumented Mexican population, although it never came into force.[iv] Most migrants stayed away from medical services due to the fear of being taken away by immigration authorities and the confusion regarding immigration’s public charge, particularly during the Trump Administration.[v] Besides, the creation of the Binational Health Week in 2001 by the government of Mexico and the Health Initiative of the Americas (HIA) gave a big push for establishing a permanent health office at the Mexican consulates that could also provide information year-round (Link to the blog post about the Binational Health Week). However, it was not that easy, as the VDS required having non-official personnel inside the consulate. Raúl Necochea López details the difficulties that had to be overcome to open the Health Desks in the consulates´ offices, as it was “a significant departure from the established restrictive norms about the use of consular resources,”[vi] The biggest issue was the permanent presence of non-consulate personnel at the consular premises. After some time, finally, in February 2002, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Mexico accepted the idea, and a pilot program proposal was developed. In 2003, the Consulates of Mexico in San Diego and Los Angeles opened the first VDS as a pilot project. After their initial success, the Ministry of Health of Mexico has provided funds for the program since 2006. Taking advantage of the hundreds of persons that visit the consulates every day was a determining factor for the health institutions in establishing a permanent health office at the consular premises. It provided access to hard-to-reach populations in a secure and culturally appropriate environment. “A key factor in the [partner organizations’] ability to reach this population is the fact that the consulate is generally considered a trustworthy space in the sense that a person´s migration status will not be at risk.”[vii] What is the Health Window? The VDS is a designed space inside the consulate, generally in the public waiting area, attended by personnel of the local partner. The Health Desk provides health-related information and personalized counseling, makes referrals to a health clinic and other specialized services, and offers the opportunity to receive different types of screening. “The VDS program is a multistrategy approach to providing personalized assistance and outreach to Mexican immigrants unfamiliar with the U.S. health system.”[viii] The Health Desk program is a public-private partnership with the participation of Mexico´s Ministry of Health (providing funding and overseeing the program), the Institute of Mexicans Abroad (IME) through the consular network, and local government and non-government health care organizations, such as community health centers, hospitals, universities, migrant-serving institutions, and pharmacies. The local partners provide human and financial resources and knowledge, while the consulates offer a space for their activities. “The aim of this initiative is to build a network of informational windows [Health Desks] to increase knowledge about health and access to services for Mexican migrants and their families residing in the United States.”[ix] The VDS provides the following general services, which vary depending on several issues, most notably the available local resource and existing partnerships:

As the program evolved, more organizations began offering health-related services, from a wide variety of screenings and immunizations to access to quitting smoking programs and referrals to community health clinics. In 2015, the VDS served 1,525,504 persons who received 415,509 screening and 63,084 vaccinations.[xi] The VDS provided a wide variety of information, including health insurance, domestic violence, hypertension, diabetes, substance abuse, obesity, birth control, and mental and women´s health, among other topics.[xii] The evolution of the Heath Desk. After its initial success, the VDS expanded rapidly like other successful consular programs. Eleven consulates established Health Windows between 2004 and 2007. And, from 2008 to 2011, an “additional 38 VDS opened for a total of 50 affiliated with the Mexican consulates that work closely and in partnership with local health-care organizations.”[xiii] Two circumstances helped in the fast expansion of the program. The first one was the creation of a health commission of the Institute of Mexicans Abroad´s Advisory Council -CCIME- in 2003. The advisory council was the first of its type in the government of Mexico.[xiv] The second situation was the increase in the reunification of women and children in the U.S.,[xv] significantly changing the demographics and needs of the Mexican migrant community. Health care has become increasingly critical for new migrant families. For example, in 2013, women were 63% of the people served by the VDS.[xvi] An additional advantage of the Health Desk was that the IME organized several Jornadas Informativas (specific topic conferences) centered on health issues. It later created a special meeting of all VDS partner organizations, which was unique to the program. In December 2020, the 17th Annual meeting of the Health Desk program took place online due to the pandemic. In 2012, a Health Advisory Board was established with nine members to define the priorities of the VDS and make recommendations to promote the program´s sustainability. The board was one of the first to be established to strengthen the programs implemented by the IME. During the Covid-19 pandemic, the VDS played a crucial role in providing information to the community via social media and other forms of communication. In 2021, Mexico´s consular network in the United States helped provide 80,000 COVID-19 vaccines[xvii] not only to the Mexican community but also to Hispanics and from other countries. Through the years, the VDS has continued to evolve. For example:

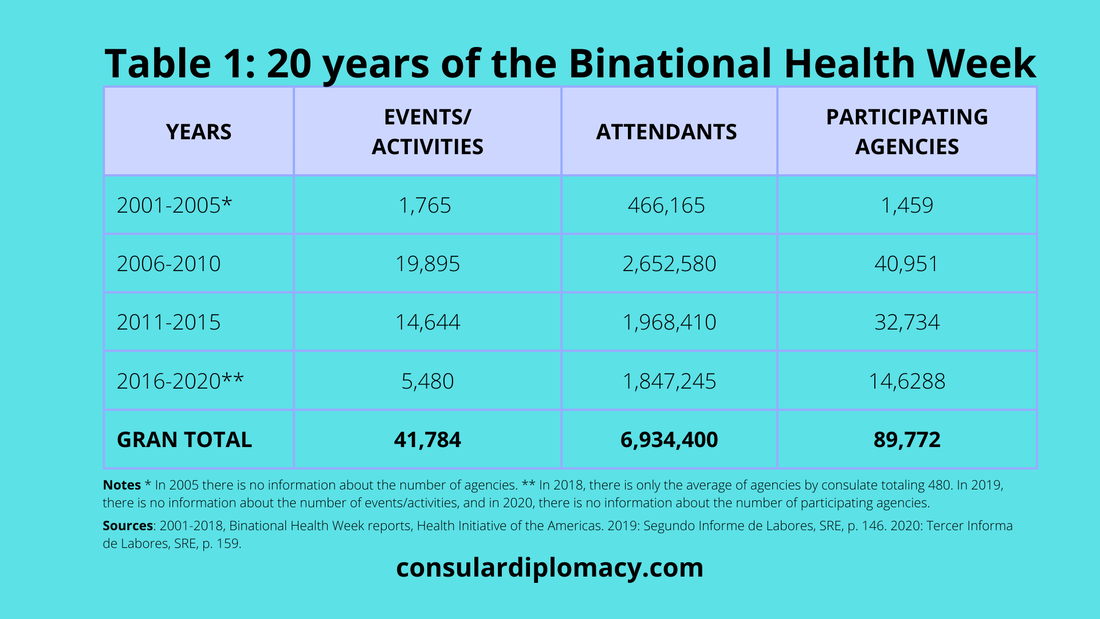

The results of the Heath Desk. From 2003 until August 2022, the VDS served 18.3 million persons and offered 45.8 million health-related services, as described in Table 1, with the collaboration of around 600 local partners. Table 1. Ventanilla de Salud Program: persons serviced, and health-related services provided from 2003 to 2022 Period Persons Services 2003-2017 10 million* 18.4 million** September 2017-August 2018 1.5 million 5.8 million January-July 2019 700,000 1.8 million September 2019-August 2020 2.0 million 6.0 million September 2020-August 2021 3.0 million 8.5 million September 2020-August 2022 1.1 million 5.3 million TOTAL 18.3 million 45.8 million Note: A single person can receive multiple services. According to the Institute of Mexican Abroad, between 2003 and 2019, the VDS served 22 million persons who received 8 million health-related services. Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior (2021). Ventanillas de Salud (VDS). 21 November. Sources: *2003-2017. Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior, 2017. Las Ventanillas de Salud reciben el premio de la OEA a la Innovación para la Gestión Pública. Boletín Especial Lazos. 11 October. **The number of services only includes from 2012 to 2016. Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior, 2018. Resultados Programa VDS. 26 November 2016; updated March 2018. 09/2017-08/2018: Sexto Informe de Labores, SRE. 2018, p. 190; 01-07/2019; Primer Informe de Labores, SRE. 2019, p. 136; 09/2019-08/2020: Segundo Informe de Labores, SRE. 2020, p. 157; 09/2020-8/2021: Tercer Informe de Labores, SRE. 2021, p. 145; 09/2021-08/2022: Cuarto Informe de Labores, SRE. 2022, p. 142. The impact of the VDS is more significant considering that health issues affect the family on both sides of the border, as illnesses and other health problems can result in a reduction of income and an increase in expenses. Besides reaching out to millions of Mexicans in the U.S. through the VDS program, the consulates of Mexico have established long-term alliances with a wide range of health-related organizations, such as the American Cancer Society, the National Institute for Health, Georgia Lighthouse Foundation, and Emery University´s Rollins School of Public Health.[xviii] The program has also strengthened its collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Alliance for Hispanic Health.[xix] Recognizing the great benefits that the VDS provided, in 2017, the Organization of American States granted the “Inter-American Award on Innovation for Effective Public Management” in the Social Inclusion Innovation category.[xx] The opening of the VDS was a defining moment in Mexico´s public-consular diplomacy, as it allowed, for the first time, the permanent presence of community health organizations personnel inside the consular premises. Shortly after, other groupings, such as the banking and financial sectors, assigned people to the local consulate. Various consulates also opened new specific-purpose windows focused on educational opportunities and financial education. More recently, some three consulates have created new desks to provide specialized care to indigenous migrants. Conclusions. The Ventanilla de Salud or Health Desk program is another example of an innovative public-consular diplomacy of Mexico, working as a bridge between the Mexican community living in the U.S. and its network of health partners. Health referrals and screenings are not typical consular assistance programs. However, the VDS was a groundbreaking way for the government of Mexico, together with local partners, to care for the needs of the Mexican community in a country without universal health care. The VDS also initiated the consulates' transformation into community centers. The VDS helps the Mexican community in the U.S. to alleviate their barriers to accessing healthcare and solving health-related issues. A visit to a Health Window in a Mexican consulate can be a life-changing event or at least an opportunity to learn how to navigate the U.S. health system. [i] Other translations of the VDS program are Health Stations or Health Windows. Here it Desk and Window will be used. [ii] Israel, E. and Batalova, J. 2020. Mexican Migrants in the United States. Migration Policy Institute. 5 November. [iii] Rosenbloom, R. and Batalova, J. 2022. Mexican Immigrants in the United States. Migration Policy Institute 13 October. [iv] Márquez Lartigue, R. 2022. Public-consular Diplomacy that heals: The Binational Health Week Program. Blog about Consular and Public Diplomacies. 5 March. [v] Marina Valle, V., Gandoy Vázquez, W. L., and Valenzuela Moreno, K. A. 2020. Ventanillas de Salud: Defeating challenges in healthcare access for Mexican immigrants in the United States. Estudios Fronterizos, 21. July. [vi] Necochea López, R. 2018. Mexico´s health diplomacy and the Ventanilla de Salud program. Latino Studies (16), p. 483. [vii] Délano Alonso, A. 2018. From Here and There: Diaspora Policies, Integration and Social Rights beyond Borders, p. 78. [viii] González Gutiérrez, C. 2009. The Institute of Mexicans Abroad, An Effort to Empower the Diaspora. In D. R. Agunias (Ed.) Closing the Distance. How Governments Strengthen ties with their Diaspora, p. 94. [ix] Dávila Chávez, H. 2014. Comprehensive Health Care Strategy for Migrants. Voices of Mexico. Num. 98, Winter, p. 96. [x] Secretaría de Salud and Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. 2019. Strategy: Ventanillas de Salud, p. 7. [xi] Rangel Gómez, M. G., et. al. 2016. Ventanillas de Salud: A Program Designed to Improve the Health of Mexican Immigrants Living in the United States. Migración y Salud, p. 100. [xii] Rangel Gómez, M. G., et al. 2017. Ventanillas de Salud: A Collaborative and Binational Health Access and Preventive Care Program. Frontier in Public Health. 30 June. [xiii] Rangel Gómez, M. G., et al. 2017. Ventanillas de Salud: A Collaborative and Binational Health Access and Preventive Care Program. Frontier in Public Health. p. 3. 30 June.[xiv] Délano, A. 2009. From Limited to Active Engagement: Mexico’s Emigration Policies from a Foreign Policy Perspective. International Migration Review, 43(4), p. 791. [xv] Durand, J., Massey, D. S. & Parrado, E. A. 1999. The New Era of Mexican Migration to the United States. The Journal of American History, 86(2), p. 525-527. [xvi] Rangel Gómez, M. G., et al. 2017. Ventanillas de Salud: A Collaborative and Binational Health Access and Preventive Care Program. Frontier in Public Health, p. 2. 30 June. [xvii] Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. 2021. Tercer Informe de Labores, SRE, p. 146. [xviii] Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior 2018. Alianzas Estratégicas. Published 24 November 2016; updated March 2018. [xix] Dávila Chávez, H. 2014. Comprehensive Health Care Strategy for Migrants. Voices of Mexico. Num. 98, Winter, p. 98. [xx] Organización de Estados Americanos. 2017. V Premio Interamericano a la Innovación para la Gestión Pública Efectiva 2017. Acta Final de Evaluaciones. Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior. 2017. Las Ventanillas de Salud reciben el premio de la OEA a la Innovación para la Gestión Pública. Boletín Especial Lazos. 11 October. Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior. 2017. La OEA hace entrega de Premio Interamericano a las Ventanillas de Salud. Press Bulletin. 19 December. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company.  I have great news for those interested in consular diplomacy. Recently, there have been a few new and fascinating publications on the subject. The evolution of the consular institution. Let´s start with the work of Iver B. Neumann and Halvard Leira, two prominent consular affairs scholars. The chapter “The evolution of the consular institution” of the book Diplomatic Tense (2020) analyzes the development of the consular institution from an evolutionary perspective. This book chapter broadens the authors' previous studies, such as “Consular Representation in an Emerging State: The case of Norway” (2008), “The many past lives of the Consul” (2011), and “Judges, Merchants and Envoys: The Growth and Development of the Consular Institution” (2013). In “the evolution of the consular institution”, Neumann and Leira examine the evolution of the consular functions, using as a reference “tipping points, understood as the culmination of long-term trends.”[i] They evaluate the process based on the concepts of variation, stabilization, and institutionalization of the consular function.[ii] The three tipping points of the consular institution identified are: