1. Introduction Recently, I had the opportunity to finally read the seminal book on Consular Diplomacy titled Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, edited by Jan Melissen and Ana Mar Fernández. This work allowed me to rethink what is Consular Diplomacy. Ten years have passed since its publication in 2011. Since then, there has been more changes to diplomacy in general and the consular institution in particular. An example of the relevance of Consular Diplomacy today is the response of all ministries of foreign affairs to the COVID-19 pandemic that required a massive effort to repatriate and assist nationals stranded overseas as the world closed in March 2020. The book is divided into three sections:

It includes articles about the history and recent developments of consular affairs of Spain, France, the Netherlands, China, Russia, and the United States, as well as consular experiences of the European Union. The order of the book is a little bit odd because it starts with consular affairs´ contemporary issues and ends with the consular history of three European nations. However, it is a great read that has tons of fascinating information and ideas. If you can only read a few chapters, I suggest checking out the following:

In the introduction, Jan Melissen identifies four conceptual or empirical observations about the development of the consular institution:

These four observations are beneficial for the reader, as they help navigate through the book´s twelve chapters and explore the concept of Consular Diplomacy. 2. Reconsidering Consular Diplomacy After reading the book, one of the first things that hit me was that each country has a unique consular affairs history, from China´s recent interest in assisting its citizens overseas to the Netherland´s reliance on honorary consuls. Learning the consular history of six countries gave me a different perspective of Consular Diplomacy in general, and specifically about the development and characteristics of Mexico´s Consular Diplomacy. I think this is one of the reasons that comparative studies in International Relations are so critical. For example, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, millions of Russian citizens suddenly lived in foreign countries, which happened to Mexicans after the 1846-1848 Mexico-U.S. War. In both cases, the two countries' governments had to step up their consular work to assist and protect their nationals, now living abroad. Another example is the problems raised from the extraterritoriality clauses of international treaties with Western powers. In Mexico´s history, foreign government´s interventions on behalf of their citizens were critical in shaping its foreign policy principles. Therefore, learning a bit about the origins of the Capitulations treaties signed between the Ottoman Empire and European powers was enlighten. Halvard Leira and Iver B. Neumann´s explanation about why the Ottoman Empire granted European nations extraterritorial jurisdiction of their own citizens is excellent for understanding a different perspective from the traditional view of European imposition of those terms.[ii] The book clearly demonstrates that the Capitulations had a significant impact on the development of the consular institution, particularly its judicial attributions. Before, I thought that Mexico´s consular institution was distinctive. However, after reading the book, now I realize that each country´s consular affairs had a specific evolution that is different from all others. Of course, there are common patterns and trends, but each nation experiences them in unique ways. The themes are similar, but the differences are in the details. This new perspective is helping me to have a deeper understanding of the differences between the consular services offered by each country, such as the distinction of providing funds for the repatriations of human remains offered by Mexico to only assisting in the paperwork done by the U.S., Canada, and others. This new understanding is making me rethink the concept of Consular Diplomacy, which is closely related to the history of the country´s consular institution. Another realization is that every country, in general, has the same diplomatic objectives, but in consular affairs, it varies depending on its specific evolution and the relationship between the government and its citizens. Therefore, I believe that Consular Diplomacy is hard to generalize. There is a need to look deeper into what Melissen states as “the long-time neglect of the societal dimension of world politics and diplomacy”[iii] to grasp the idea of diplomatic activities in the consular realm. 3. The division between diplomacy and consular affairs persists but is narrowing The second impression of the book is that the link between diplomacy and consular affairs has always been there, but it has changed as societies and the international arena evolved. Even today, after the rise of the Consular Diplomacy, the division between the two still exists. There is not a single path for the relationship between the two. Each country has its own. However, the incorporation of consular responsibilities to the ministries of foreign affairs from the 17th Century onward is a common feature in most nations. The consular history of the six countries demonstrates the highly complex interaction of the two services. To me, their amalgamation in the early 20th Century did not diminish the perception of consular affairs as a Cinderella´s service. It is not till the end of the 20th Century, as Maaike Okano-Heijmans explains in “Change in Consular Assistance and the Emergence of Consular Diplomacy”, that consular affairs become a true priority not only for the foreign ministries but the government as a whole.[iv] It is then, when globalization speeded up, together with the digital revolution and the democratization of diplomacy, when Consular Diplomacy was able to break through its `glass ceiling´ and become an openly acknowledged core activity of foreign ministries. The modernization and standardization processes that consular affairs have endured in the last 20 years to meet the ever-higher expectation of the public is a clear example of the new status of consular services. Even after the unification of the diplomatic and consular services, most countries still see them as separate entities. The existence of two Vienna Conventions (one for each) is the perfect example of this division. By the early 1960s, when the conventions were discussed, the fusion of the two services was widespread. Why was it so difficult to merge both in just one convention? 4. A greater understanding of the evolution of the consular institution. The book allows the reader to understand better the multiple responsibilities that consuls had, from being judges, tax collectors, trade promoters, and sometimes even chaplains.[v] No wonder there is still a lot of misconceptions about what consuls do nowadays. Even the word `Consul´, is still mixed up with `Counsel´ (law-related) and `Councilor´ (city authority), which in the past were some of the main attributions of the position. Through centuries, and as the Westphalia state-system developed, the consular institution experienced a gradual process of specialization of its functions. Consuls slowly were stripped of some of their core responsibilities[vi] and focused on two critical issues of today´s consular affairs: documentary services and assistance to citizens in distress abroad. At the same time, it seems that a process of homogenization took place in international relations that affected the consular institution. As the articles about the six countries exhibit, consular affairs worldwide suffered the same transformations and are now mostly limited to documentary services and the protection of their nationals. Maybe the concentration on these two activities helped in its rise to the top of the foreign policy agenda? In contrast, there is not such massive evolution of the functions of diplomats. Since the early days, their fundamental responsibilities of representation, negotiation, and communication, including information gathering, have changed little, even with drastic advances in communications and transportation. 5. The connection between public and consular diplomacies It is stimulating to see that Melissen links Public and Consular Diplomacies. “In spite of all their differences, consular work and public diplomacy are somehow kindred activities. To all intents and purposes, both are evidence of new priorities and changing working practices in foreign ministries.”[vii] I think the association between public and consular diplomacies is particularly relevant in the visa policies that directly affect the country´s image among the other nation´s citizens, as the article about the EU´s visa policy clearly showcases.[viii] I consider that, in some cases, both go hand-in-hand and are closer than we usually think. In the case of Mexico´s it may be one and the same, as I wrote in my blog post titled “Public-Consular Diplomacy at its Best: The case of the Mexican Consular ID program”. Besides, Diaspora Diplomacy is also related to Public and Consular foreign policy efforts. The idea of the connection between Public and Consular Diplomacies needs to be looked at in a deeper perspective. Hopefully, I can do this in the not-so-distant future. 6. Conclusion Jan Melissen wanted the book to “hopefully break some new ground”[ix], which I think it definitely did. Since its release, there have not been works of such dimensions;[x] therefore, it is still the standard-bearer of Consular Diplomacy and a must-read for anybody interested in the consular institution. Consular Affairs and Diplomacy is an excellent contribution to the field of study, as it associates the history and development of the consular functions with contemporary tendencies of consular affairs. It also demonstrates the always present interrelation of diplomacy and consular services, regardless of its priority ranking. In a time of a drastic reduction of the State in the international arena, consular affairs are an area that has experienced the opposite. This is partly because of the ever-growing demand and expectations of citizens abroad (and their families at home). Also, since the consular function was never part of the great division between foreign and domestic policies.[xi] For me, the work made me think again about Consular Diplomacy, mainly as a result of the relationship between the government and its citizens, not just part of foreign policy and diplomacy. There is definitely a need for more works like Consular Affairs and Diplomacy. Hopefully, there will be more coming as Consular Diplomacy continues to rise in the field of International Relations and Diplomacy studies. You can also read additional posts about consular diplomacy, such as:

[i] Melissen, Jan, “Introduction The Consular Dimension of Diplomacy” in Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, Jan Melissen and Ana Mar Fernández (Ed), 2011, pp. 1-4. [ii] Leira, Halvard and Neumann, Iver B., “The Many Past Lives of the Consul” in Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, 2011, pp. 225-245. [iii] Melissen, Jan, “Introduction” in Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, Jan Melissen and Ana Mar Fernández (Ed), 2011, p. 2. [iv] Okano-Heijmans, Maaike, “Change in Consular Assistance and the Emergence of Consular Diplomacy” in Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, 2011, pp. 21-42. [v] See, for example the consular responsibilities of French consuls in Ulbert, Jörg, “A history of the French Consular Services” in Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, 2011, pp. 307-313. [vi] For example, in France, with the creation of trade attachés in 1919, consulates were stripped from one of their original responsibilities: trade. [vii] Melissen, Jan, “Introduction” in Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, 2011, p. 2. [viii] Wesseling Mara, and Boniface, Jérôme, “New Trends in European Consular Services: Visa Policy in the EU Neighbourhood” in Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, 2011, pp. 115-144. [ix] Melissen, Jan, “Introduction” in Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, 2011, p. 1. [x] Since the book´s publication, there are some very interesting works released, like the The Hague Journal of Diplomacy´s special volume dedicated to `The Duty of Care´, published in 2018, and Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior volume on Consular Diplomacy (2014), and the books La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en Tiempos de Trump (2018), The Duty of Care in International Relations: Protecting Citizens Beyond Borders (2019), and Modern Consuls, Local Communities and Globalization (2020). [xi] Melissen, Jan, “Introduction” in Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, 2011, p. 2. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company.

0 Comments

1. Introduction As I mentioned in my previous post, “Focus on Women: Specialized Consular Assistance in the United States”, today I am writing about another example of a successful public-consular diplomacy effort implemented by Mexico in the United States: The development of specialized consular care protocols. This initiative resulted in the publication of three protocols that provide detailed information to consular officials to offer specialized consular assistance to victims of human trafficking and gender-based violence, as well as migrant unaccompanied children and teens. These three issues usually have a more significant impact on women than men, so they focus on them. The effort is quite interesting from different perspectives:

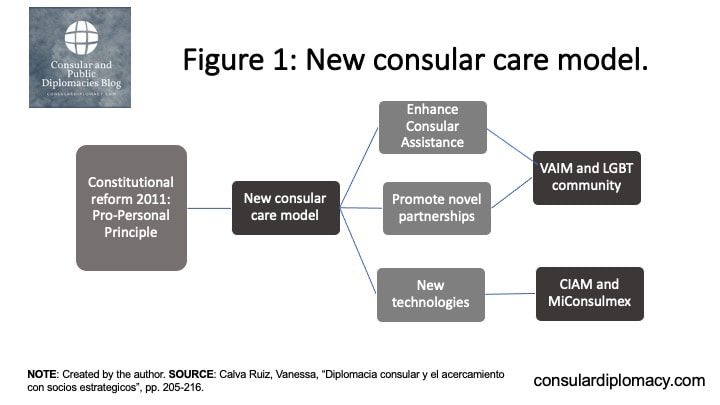

This post will cover the origins of specialized consular care and the three protocols created as part of this initiative. 2. Origins of specialized consular care In the late part of the first decade of the new millennium, Mexico’s Congress assigned funding to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (SRE) to provide consular assistance to victims of mistreatment (maltrato) with particular emphasis on women, children, and senior citizens, and victims of human trafficking.[ii] As part of the effort, the Department of Consular Assistance to Mexicans Abroad (DGPME, in Spanish) included in its regulations two new subprograms: Gender equality and Consular assistance to Mexican victims of human trafficking in 2012.[iii] The congressional funding helped consulates to support consular cases and the establishment of new partnerships. All these activities promoted a better understanding of these vulnerable groups’ particularities and the need to have better tools to assist them, including training of consular officials and the community at large. Therefore, there was a need to work on new instruments to provide specialized assistance to vulnerable groups. Besides, Mexico’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs established a new consular care model using the “pro-persona” principle as a result of the Human Rights Constitutional amendment of 2011.[iv] Since then, Consulates started cooperation pilot projects with different stakeholders, including the Ventanilla de Atención Integral para la Mujer or the “Initiative for the Comprehensive Care of Women” (VAIM) in Kansas City Missouri, in 2015. See post here. Meanwhile, in Mexico, the DGPME began working on the creation of a protocol to attend unaccompanied children and adolescents (UCA) detained at the border by U.S. immigration officials. 3. Protocol for the consular care of unaccompanied migrant children and adolescents In 2014, the DGPME agreed with UNICEF Mexico´s office to develop a consular assistance protocol focusing on unaccompanied children and adolescents. This happened as the number of the detention of Central American unaccompanied minors soared in the Mexico-U.S. border due to a non-repatriation policy of non-Mexican UCA implemented by the Department of Homeland Security. The protocol was a milestone in consular care, as it radically changed the way consular officials approached and interviewed Mexican unaccompanied children and adolescents. It was very revealing that the protocol investigators identify the consular interview as a critical moment for the children.[v] The Minister of Foreign Affairs announced the Protocol in May 2015, together with the President of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and UNICEF’s Chief of Child Protection.[vi] As part of its implementation, the Ministry undertook the broadest training program ever conducted. All personnel of the department of protection of 27 consulates participated in one of the six seminars that took place in three cities in the U.S.[vii] In total, 200 consular officials participated in this effort.[viii] The training included children and adolescents’ psychology, so consular officials were better prepared to obtain as much information as possible in a friendly, non-threatening way. This, in turn, was very useful for their future family reunification, either in Mexico or the U.S. “The Protocol has been structured based on the “inquire by informing” technique, which looks at building trust between the interviewer and the interviewed children and adolescents, so as not to depersonalize them. The Toolbox takes the same approach and is an instrument to apply the Protocol.”[ix] Thus, the Protocol’s toolkit (Caja de Herramientas) includes different items that assist the consul in interacting with UCA, such as playing cards with various images, colored pencils, and some toys. Because the idea behind the protocol’s development was also to share it with other countries, an effort was made to translate it into English. For example, as part of the Regional Conference on Migration, Mexico shared the Protocol and its implementation experience.[x] The launching of the protocol coincided with the negotiation of the renewal of the Mexico-U.S. Local Repatriation Agreements; therefore, there was an opportunity to agree with the DHS agencies on the facilitation of implementation of the protocol at the border.[xi] An essential part of the protocol development, several specialized organizations reviewed it, so it was as comprehensive as possible.[xii] It was an innovative approach as it was the first time it was done. Besides the initial training, UNICEF and the SRE agreed to do a “Train the trainer” program, so new consular officials were instructed as needed. Together with the Instituto Matías Romero (Mexico´s diplomatic academy), UNICEF created an online course about the Protocol to expand training capabilities further.[xiii] Nowadays, it is usually offered twice a year. In 2015, “there were about 13,000 cases of consular protection for migrant children and the protocol and its innovative electronic registration platform helped improve monitoring and coordination with Mexican authorities such as the National Migration Institute and the National DIF.”[xiv] 4. Protocol for the Consular Care of Victims of Gender-Based Violence While the first protocol was being rollout, the SRE started to work on the second specialized consular care protocol focused on victims of gender-based violence.[xv] In November 2015, the Minister signed an agreement with Mexico’s UN Women Office to develop the Protocol for the Consular Care of Victims of Gender-Based Violence. The first draft was presented in July 2016.[xvi] The protocol was finished in 2016 and published in 2017. The training was provided to officials in charge of the consular assistance departments in consulates across the U.S. As in the previous protocol, a group of specialized organizations reviewed the protocol before its publication.[xvii] The VAIM incorporated the Protocol’s practices and recommendations into the assistance to women, or men, who suffered from domestic violence to provide better consular care and offer all the consulate’s programs and initiative to take care of their needs. The protocol helped consular officials identify local allies that could provide services to the victims, including housing, clothing, and assistance to find a job. 5. Protocol for the Consular Care of Mexican Victims of Human Trafficking Abroad After overcoming some obstacles, in 2018, the SRE was finally able to create its third specialized protocol, which focused on Mexican victims of human trafficking abroad. On March 6, 2018, the Undersecretary for North America and the Director of the International Organization for Migration Mexico’s Office signed an agreement to develop this protocol jointly.[xviii] The International Organization for Migration was a perfect partner for its creation. Its Mexico office previously worked in the elaboration of at least two protocols regarding human trafficking victims. Besides, it was working on the subject in the framework of the Regional Conference on Migration. One difference from the two previous protocols was that as part of the Mexico-U.S. collaboration, the Embassy of the United States in Mexico partially funded the protocol’s development.[xix] It is an example of working together to tackle a crime that is not limited by borders and where migrants are particularly vulnerable. As in the previous two protocols, several specialized organizations participated in the review process.[xx] The SRE officially launched the protocol on November 22, 2018.[xxi] Following the best practice of elaborating an online course to have a permanent training tool for new consular officials, in 2019, the DGPME and the Instituto Matías Romero put together a virtual module about the subject. It is now offered regularly. Human trafficking, like gender-based violence, are topics that are a significant concern for law enforcement offices; therefore, they were gateways for collaboration, sometimes with authorities that did not like or care about migrants. Consulates participated in different ways, like becoming members of local task forces, establishing strategic alliances, and even signing MOUs.[xxii] A great example of the collaboration that resulted from the greater emphasis on assisting human trafficking victims is the one developed with Polaris. This organization manages the national human trafficking hotline in the U.S. It has trained consular officials for several years now. Also, the consulates have participated in some Polaris outreach activities.[xxiii] Most importantly, they work together when they identify a Mexican victim of human trafficking. In recognition of the assistance provided to Mexicans in the U.S., the Embassy of Mexico in Washington bestowed Polaris the Ohtli Award in September 2020. 6. Conclusions The combination of better knowledge about the needs of the Mexican migrants in the U.S. and the new focus on the person propelled the consular network to provide specialized consular care to vulnerable groups. To achieve this goal, the SRE enlisted three international partners' assistance to develop the protocols of consular care of UAC and victims of human trafficking and gender-based violence. The development and implementation of the consular care protocols changed the mindset of consular officials. Besides, the Mexican consulates actively searched for and expanded partnerships to elevate the services provided to these vulnerable groups. An important reason behind the collaboration with UN specialized organisms in elaborating the three protocols was their expertise and the opportunity to incorporate international standards, not only to the document but also to its implementation. By focusing on issues that heavily affect migrant women, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is moving forward to gender equality in the consular services it provides to the Mexican community in the United States. And by doing these has significantly expanded the reach of its public-consular diplomacy. [i] Okano-Heijmans, Maaike, “Change in Consular Assistance and the Emergence of Consular Diplomacy”, Netherlands Institute of International Relations ´Clingendael´, February 2010. [ii] Márquez Lartigue, Rodrigo, “Focus on Women: Specialized Consular Assistance in the United States”, Consular and Public Diplomacies Blog, March 8, 2021. [iii] In 2017, the program and subprograms were updated to its current name: Normas para la Ejecución del Programa de Protección Consular a Personas Mexicanas en el Exterior, SRE, May 2017. [iv] Calva Ruiz, Vanessa, “Diplomacia Consular y acercamiento con socios estratégicos” of the book La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, 2018, p. 206. [v] Gallo, Karla, “En el camino hacia la protección integral de la niñez migrante”, UNICEF México Blog, August 21, 2019. [vi] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Mexico, 3er Informe de Labores de la SRE 2014-2015, 2015, p. 195. [vii] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Mexico, 3er Informe de Labores de la SRE 2014-2015, 2015, p. 191. [viii] Gallo, Karla, 2019. [ix] SRE-UNICEF, Toolbox Pedagogical Basis, 2015, p. 3. [x] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Mexico, “The Foreign Ministry enhances its consular diplomacy and protection for Mexicans abroad”, Press Bulletin, December 29, 2015. [xi] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Mexico, 4o Informe de Labores de la SRE 2015-2016, 2016, p. 191 [xii] To see the list of organizations that participated in the review process, view page 64 of the Protocol. [xiii] Gallo, Karla, 2019. [xiv] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Mexico, “The Foreign Ministry enhances its consular diplomacy and protection for Mexicans abroad”, Press Bulletin, December 29, 2015. [xv] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Mexico, “The Foreign Ministry enhances its consular diplomacy and protection for Mexicans abroad”, Press Bulletin, December 29, 2015. [xvi] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Mexico, 4o Informe de Labores de la SRE 2015-2016, 2016, p. 200. [xvii] To see the list of organizations that participated in the review process, view page 96 of the Protocol. [xviii] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Desarrollaran la SRE y la Organizacion Internacional para las Migraciones un protocolo de atención a víctimas de trata”, Press Bulletin, March 6, 2018. [xix] Protocolo p. 101 [xx] To see the list of organizations that participated in the review process, view page 101 of the Protocol. [xxi] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “La Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores presenta el ´Protocolo de Atención Consular para Víctimas Mexicanas de Trata de Personas´”, Press Bulletin, November 22, 2018. [xxii] See for example the collaboration mechanism described in the Protocol, pp. 87-88. [xxiii] Polaris Organization, “Engaging Consulates in the Fight Against Sex Trafficking from Mexico”, Polaris Blog, May 22, 2017. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company.  As part of the celebration of International Women´s Day, I will write about a topic that is not well known but very relevant: specialized consular assistance for Mexican women in the United States. It is one of the many examples of the successful implementation of public consular diplomacy by Mexico. The conclusion is that this initiative forced the Mexican Consular network in the U.S. to seek new partnerships with local organizations that further expanded the reach of Mexico´s public consular diplomacy. 1. Origins of a specialized consular care In the late part of the first decade of the new millennium, Mexico’s Congress assigned funding to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (SRE) to provide consular assistance to victims of mistreatment (maltrato) with particular emphasis on women, children, and senior citizens. Later on, in 2011, due to the Human Rights Constitutional amendment that adopted the “pro-persona” principle, the SRE established a new consular care model emphasizing specialized assistance to vulnerable groups.[i] Mexico´s consulate began engaging with local and state authorities, NGOs, and the Mexican community to enhance the consular assistance to these groups. As part of these efforts, they strengthened their collaboration with traditional partners and expanded cooperation with new organizations. Some consulates established strategic alliances and designed new initiatives. An example of these partnerships was promoting the “Violentrometro” or the violence against women measuring ruler. As part of these collaborations, the Consulate of Mexico in Kansas began a pilot program offering comprehensive services for Mexican women that visited its office or participated in their events. Besides, at the Ministry´s headquarters, the Department of Consular Assistance to Mexicans Abroad (DGPME, in Spanish) spearheaded with UNICEF Mexico an effort to create a tool to improve consular assistance to unaccompanied Mexican children detained at the border. In the next section, I will detail one of the most important specialized consular assistance programs that focus on women: the Initiative for Comprehensive Care of Women (Ventanilla de Atención Integral para la Mujer -VAIM-). In a different post, I will write about the other program: the consular care protocols focused on unaccompanied children, gender-based violence, and human trafficking. 2. Initiative for Comprehensive Care of Women (Ventanilla de Atención Integral para la Mujer -VAIM-) As mentioned, the Ventanilla de Atención Integral para la Mujer or the “Initiative for the Comprehensive Care of Women” (VAIM) began as a pilot program in Kansas City in May 2015.[ii] Its objective is to interconnect all areas of the consulate to offer specialized assistant to Mexican women. Besides, it promotes training and sensibilization about their challenges and creating a resources and a services directory.[iii] Its ultimate goal is to empower women in all aspects of their lives.[iv] “In the framework of Consular Diplomacy, the VAIM boosted actions to provide consular assistance [to women] through the establishment of an important network of strategic alliances. [The Consulate in Kansas] signed 18 memoranda of understanding that resulted in a wide range of benefits to the women that requested assistance.”[v] Besides, there was a great effort to train law enforcement officers about the consular functions, collaboration mechanisms, and consular notification.[vi] As part of the 2016 International Women´s Day celebration, the SRE announced the expansion of the VAIM to all the consulates in the United States.[vii] It was an important milestone as it was a whole-of-consulate approach. Mexico´s consulate had to be proactive in developing and strengthening alliances with new and old stakeholders. “The creation of a strategic support structure allows increasing resources, early detection of potential cases, providing better consular care and expanding additional outreach channels.”[viii] From March 2016 to June 2018, the Mexican consular network organized 5,088 VAIM outreach events with a total participation of 387,980 persons and consular assistance provided to 10,627 cases.[ix] 3. Conclusions. The establishment of VIAM highlights the versatility of Mexico´s public consular diplomacy. As many Mexican women and children migrated north, the community's needs changed; therefore, the consular care offered by the consular network had to change too. There were efforts focus on assisting women, but the VAIM was a milestone as it was comprehensive consular care, not focused on one issue, but searching to offer as many consular services as needed. I believe that the most important result of the VAIM was a change in the mindset of not only consular officials but also the Mexican community at large and local allies about the need to provide specialized consular care to Mexican women. It was a significant change as in the past, most consular assistance was provided to men, as they were the majority of migrants to the U.S. Besides, it opened the door for a whole new set of allies and strategic partnerships that enhance the consular care given to Mexican women, which opened the doors for empowering them. Vanessa Calva Ruiz explains that “the establishment of partnerships not only takes care of urgent needs of the Mexican community but also assist them in integrating to the host society by linking them with local actors that offer resources.”[x] [i] Calva Ruiz, Vanessa, “Diplomacia Consular y acercamiento con socios estratégicos” of the book La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, 2018, p. 206. [ii] Gómez Maganda, Guadalupe and Kerber Palma, Alicia, “Atención con perspectiva de género para las comunidades mexicanas en el exterior” in Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior, No. 107, May-August 2016, p. 197. [iii] Calva Ruiz, Vanessa, 2018, pp. 208-209. [iv] Gómez Maganda, Guadalupe and Kerber Palma, Alicia, 2016, p. 197. [v] Ibid. [vi] Gómez Maganda, Guadalupe and Kerber Palma, Alicia, 2016., pp. 197-198 [vii] Government of México, 4º Informe de Labores SRE· 2015-2016, 2016, pp. 189, 201. [viii] Calva Ruiz, Vanessa, 2018, pp. 209-210. [ix] Government of México, 6º Informe de Gobierno 2017-2018, 2018, p. 681. [x] Calva Ruiz, Vanessa, 2018, pp.213-214. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer, or company.  Following up on my previous blog post about the surge of “new” diplomacies and the discussion of whether these initiatives a real diplomatic instruments or just imposters, today I will analyze the case of Consular Diplomacy. The conclusion is that while Consular Diplomacy meets all the qualifications to be considered a real diplomatic tool to attain a foreign policy goal, the lack of studies seriously hinders its development. Therefore, it is finally leaving Cinderella's status but is not yet considered a princess, like Public or Cultural Diplomacies. Note: The reference to consular affairs as “Cinderella” was made by D.C.M. Platt in his book The Cinderella Service: British Consuls since 1825. Maaike Okano-Heijmans and Jan Melissen used the term in their paper Foreign Ministries and the Rising Challenge of Consular Affairs: Cinderella in the Limelight. 1. Previous post summary “New” Diplomatic Tools: Imposter Diplomacy or the Real Deal? Shaun Riordan and Katharina E. Höne have expressed their concern about the tendency to incorporate into the diplomatic realm all sorts of activities, which carries the risk of losing the meaning of Diplomacy.[i] To uncover Imposter Diplomacy and confirm the realness of new diplomatic tools, Höne proposes that “rather than a categorical rejection [of the new diplomacies], the proper response is to sharpen our intellectual tools and get to work [and] to tell the imposter from the innovator, we need to look closely at diplomacy as a practice, its relation to the state, and the purposes of these new diplomacies.”[ii] In the previous post, I already analyzed Public and Gastronomic Diplomacies. I conclude that the former could be categorized as a new diplomatic tool, while the latter is still too early, despite investments made by various governments.[iii] 2. Consular Diplomacy rising Despite being older than traditional Diplomacy and at one point much more widespread, the consular function has always been relegated. Only now, in the 21st Century, consular services have received greater attention by not only public officials, including diplomats, but also by politicians, regular citizens, and the media. In the paper, Foreign Ministries and the Rising Challenge of Consular Affairs: Cinderella in the Limelight, Maaike Okano-Heijmans and Jan Melissen explain why consular affairs changed from being the Cinderella of diplomacy to be a high priority for the ministries of foreign affairs (MFAs), the general public, the media, and politicians worldwide. However critical the increasing number of terrorist attacks, the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami, the 2010-11 Arab Spring, and, more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic, Okano-Heijmans and Melissen indicate that the greater interest in consular issues did not develop with the arrival of the internet or social media. It arose during the intra-war years and resulted in the integration of diplomatic and consular services.[iv] and later, with the changes in communications, technology, and transportation. One reason why consular issues are just now rising into prominence in the diplomatic world is that the amalgamation of the consular and diplomatic services is relatively recent, from a historical perspective. In 2022 and 2024 will be the 100th anniversary of the two branches' fusion in Norway and the US, respectively. However, it is a lot more recently for other countries like Great Britain (1943) and Italy (1952).[v] I think that the merging of both services has not been totally completed. The view from inside and outside the Foreign Ministries about the two divisions remains separated. For example, there are two different Vienna Conventions, one specific for Diplomatic Relations and the other regarding Consular Relations. This came about when the combination of the two services already happened in many countries. All this is a bit ironic because, as Jan Melissen states in “Introduction The Consular Dimension of Diplomacy” for most ordinary people, the Ministry's face is not a diplomat seating in an embassy, but a consular official either providing documentary services or consular assistance or promoting trade and better relationships with local and state authorities and civil societies.[vi] It is relevant to know that consular services are more in-tuned with the new realities of 21st Century Diplomacy, such as its focus on strengthening performance thru a service-oriented perspective, the familiarity of intermestic issues, and greater collaboration with new partners.[vii] The consular function's qualities help consular affairs be more visible inside and outside the MFA, ascending to a new level. 3. Is Consular Diplomacy a new diplomatic tool? I will now follow Höne´s recommendation of evaluating the new tools by looking at Diplomacy as a practice, its relation to the state, and its purpose. 3.1 The practice of Consular Diplomacy As mentioned before, consular posts predate permanent embassies in Europe for a couple of hundred years. While in the beginning, consuls were not public officials, sometimes performed duties as authorities. In the hey-days of consular affairs, during the 19th Century, consular officials were also involved in diplomatic activities, even if they were not recognized.[viii] From a comparative standpoint, consular affairs is a lot older than almost all diplomatic tools, such as Public, Cultural, and Multilateral Diplomacies. Its problem is that it is considered a technical function, not as crucial as any diplomatic activity. The countries´ little interest in consular affairs is demonstrated by the fact that the first and only international convention on the subject was negotiated in the 1960s. From a practical perspective, I can understand the different visions between diplomats and consuls. The question of representation and what it entails in terms of protocol, image, and status is enormous among the two. It is totally dissimilar to work in the halls of palaces, presidential offices, and the MFAs than in ports, jails, and other local venues. The distinction is a heavy-weight on consuls' images, and even today, when they are no longer seen as Cinderellas, consular officials have not yet arrived at palaces, presidential offices, or foreign ministers´ desks. Consular affairs is an established responsibility of MFAs that date back centuries, and it has developed into a profession and a practice. There are no doubts about Consular Diplomacy's existence and heritage; however, it has not yet reached a point to be recognized as a useful foreign policy instrument, with a few exceptions. The fact that almost none country utilizes the term regularly is a perfect example that still is underrecognized, even if MFAs undertake actions that could fall into its category. 3.2 Relation to the state Despite the growing outsourcing of certain consular functions and the greater collaboration between consulates and authorities, civil society, and their diaspora, it is evident that it is a government´s responsibility to provide consular services to its citizens abroad and other groups. Consular officials in their corresponding districts are the only ones to execute activities such as visiting prisons and jails, issuing passports and birth certificates, and promoting the country´s image in the host nation. It is a non-delegable function restricted to government officials. Therefore, I can attest that Consular Diplomacy fulfills the requirement to be considered a diplomatic tool rather than an imposter. It can only be performed by the government and its representatives. 3.3 Pursuing Foreign Policy goals There is no doubt that consular affairs are a vital function of the ministry of foreign affairs. However, it is a bit more challenging to attest whether these activities help achieve its Foreign Policy (FP) goals. For countries with relatively low immigration and limited travel opportunities for their citizens, consular affairs might be just a public policy that happens to be offered overseas. In contrast, states with significant diaspora communities and extensive traveling communities might incorporate some FP goals into the management of their consular affairs, such as providing efficient consular services to their nationals and foreign citizens or enhancing consular collaboration with other countries. In many cases, the MFA´s primary concern is the domestic dimension rather than an actual foreign policy objective; however, consular cases' reputational impact is quite high and is the main reason for its recent upgrade.[ix] For both types of countries, a high visibility consular case can turn into a diplomatic situation affecting bilateral relations, even making decisions against their national interests.[x] 3.4 Consular Diplomacy´s missing dimension: studies As I did in the Public and Gastronomic Diplomacies cases, I am also reviewing the Consular Diplomacy´s study field. Sadly, in this area, this new diplomatic tool is still in its infancy. The only known course about the topic “Consular and Diaspora Diplomacy” is offered by the DiploFoundation. However, it has not being offered for the last few years, perhaps demonstrating the lack of interest in the subject. As Okano-Heijmans and Melissen indicate, “consular affairs [do not] appeal sufficiently to students of diplomacy to merit much study and reflection;”[xi] therefore, there is a severe absence of studies about this matter. Regarding scholarly work, the only book about the issue is the 2011 Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, edited by Jan Melissen and Ana Mar Fernández. Astonishingly, the book is ten years old, and since then, no new scholarly book about the subject has appeared. There is the book The Duty of Care in International Relations: Protecting Citizens Beyond the Border published in June 2019. Also, The Hague Journal of Diplomacy dedicated the issue #2, Vol. 13, March 2018, to the topic and was titled “Diplomacy and the Duty of Care.” I am not sure if both discuss Consular Diplomacy, as I have not read them yet. In Mexico, a special issue (#101) of the Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior about the subject was published in 2014. Additionally, the book La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en Tiempos de Trump, written from a practitioner's perspective, came out in 2018. I just learned that Brazil´s MFA issued in 2012 a report titled Diplomacia Consular 2007 a 2012. A few countries, like Canada, Australia, and the Netherlands, have sponsor studies about consular affairs, but none of them use the term Consular Diplomacy often. I don´t understand why there is minimal production of scholarly works and practitioners' essays about this matter. Around the world, there are more consular officers than diplomats performing other duties. As mentioned above, consular agents are the faces of the MFAs to citizens overseas and domestic audiences. One reason might be that consular officials are always too busy solving the newest crisis and a high-level consular assistance case or issuing consular documents to write about their experiences. Privacy limitations are also an obstacle for more research, but I am sure they can be overcome to have more studies about consular affairs. Another cause might be the scarcity of funding, if there is money at all, for research in the field; thus, there are no incentives for up-and-coming scholars, universities, and think tanks to tackle the issue. As the Global Consular Forum[xii] has demonstrated, many countries are interested in expanding the collaboration in consular affairs and are willing to exchange best practices; thus, there is no lack of interest in many MFAs about the subject. With consular services’ new visibility and the need to improve them, I believe that Consular Diplomacy research will grow, but it needs a boost. 4. Conclusions: Does Consular Diplomacy is an imposter or the real deal? For a citizen, the consular function does not carry the significance of the “glamour” of diplomatic life, negotiating a world-changing agreement in New York or Geneva's halls. However, in time of need, very few public officials have the preparation, ability, and ingenuity to solve their problems. Consuls are like the police or the fire department; you just call them in an emergency, but they can change your life. There is an enormous need for more consular studies, but not just to evaluate its performance but to contribute to the surge of a real Consular Diplomacy one day. Ironically, Consular Diplomacy fulfills all the qualifications of a “new” diplomatic tool; however, there is such a tiny body of work that it is hard to confirm its realness. Consular Diplomacy as a “new” diplomatic tool is finally out of its Cinderella´s reference; however, there is still a long way to reach the status of a princess. You can also read additional posts about consular diplomacy, such as:

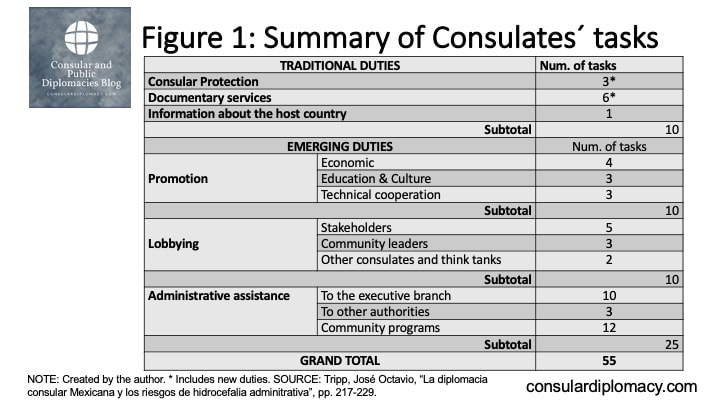

[i] Riordan, Shaun, “Stop Inventing New Diplomacies”, Center on Public Diplomacy Blog, June 21, 2017 and Höne, Katharina E., “Would the Real Diplomacy Please Stand Up!”, DiploFoundation Blog, June 30, 2017. [ii] Höne, Katharina E., 2017. [iii] Márquez Lartigue, Rodrigo, ““New” Diplomatic Tools: Imposter Diplomacy or the Real Deal?” In Consular and Public Diplomacies Blog, February 22, 2021. [iv] Heijmans, Maaike and Melissen, Jan, in Foreign Ministries and the Rising Challenge of Consular Affairs: Cinderella in the Limelight, Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael, June 7, 2006, p. 5. [v] Berrigde, G.R., Diplomacy: Theory and Practice, 5th ed., 2015, p. 136. [vi] Melissen, Jan, “Introduction The Consular Dimension of Diplomacy” in Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, 2011, p. 3. [vii] Melissen, Jan, 2011, pp. 4-6. [viii] Heijmans, Maaike and Melissen, Jan, in Foreign Ministries and the Rising Challenge of Consular Affairs: Cinderella in the Limelight, Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael, June 7, 2006, pp. 3-4. [ix] Heijmans, Maaike and Melissen, Jan, 2006, pp. 6-7. [x] Okano-Heijmans, Maaike, “Changes in Consular Assistance and the emergence of Consular Diplomacy” in in Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, 2011, pp. 24-26. [xi] Heijmans, Maaike and Melissen, Jan, 2006, p. 1. [xii] The Global Consular Forum is “an informal, grouping of countries, from all regions of the world fostering international dialogue and cooperation on the common challenges and opportunities that all countries face today in delivery of consular services.” Wilton Park, “Global Consular Forum 2015 (WP1381)”. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer, or company.  This post was originally published February 4, 2021, by the CPD Blog at the USC Center on Public Diplomacy here uscpublicdiplomacy.org/blog/public-consular-diplomacy-its-best-case-mexican-consular-id-card-program. We look forward to sharing widely and hope you´ll do the same. The Mexican Consular ID card (MCID or Matrícula Consular) program is considered a successful public-consular diplomacy initiative. It resulted in significant benefits for the Mexican community living in the United States, creating long-lasting partnerships between Mexican consulates and local authorities, and financial institutions. With the focus on security in the U.S. after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, Mexico's government decided to increase the security features of the MCID, which has been produced by the consulates since 1871. Consular offices started issuing the new high-security consular IDs cards in March 2002 while there were changes in banking regulations due to the USA Patriot Act of 2001. Besides the new security features, the Matrícula included additional information useful for local authorities and banks, such as the bearer's U.S. address. These added characteristics allowed banks, police departments and sheriffs' offices across the United States to appreciate it as a valuable tool and begin to recognize it as a form of ID. Despite pressure from anti-immigrant groups, the Treasury Department reaffirmed banks' possibility of accepting foreign government-issued identification documents, including the MCID, in September 2003. Wells Fargo was the first bank to accepted it and opened 400,000 bank accounts using the Matrícula from November 2001 to May 2004. Other financial institutions quickly followed. Therefore, by 2010, 400 financial institutions did the same, and 17 consulates signed 45 agreements with banks and credit unions. The Mexican Consular ID card was also seen as a step toward the financial inclusion of Latinos and immigrants; hence, the Federal Deposits Insurance Corporation (FDIC) promoted the collaboration with Mexico's consular network across the United States through the New Alliance Task Force. The benefit for the Mexican community was dramatic and very concrete. Having a bank account opened the door of financial inclusion. The Matrícula acceptance jumped dramatically in a short time. Consequently, as of July 2004, the Mexican Consular ID card “was accepted as valid identification in 377 cities, 163 counties, and 33 states…as well as…1,180 police departments…and 12 states recognize the card as one of the acceptable proofs of identity to obtain a driver's license.” After a hard pushback against issuing driver's licenses to undocumented migrants, some states reconsidered their position. “As of July 2015, 12 states…issued cards that give driving privileges...[to them]. Seven of these came on board in 2013.” Some states recognize the Matrícula as a form of identification for obtaining a driver's license, even as the implementation of the REAL ID Act of 2005 is finally moving forward. The search for the acceptance of the consular ID cards pushed consulates, for the first time as a large-scale operation, to reach out to potential partners, including banks, credit unions, city mayors, country supervisors, chiefs of police and sheriffs' officers across the U.S. They also met with local institutions such as libraries and utility companies to promote the benefits of the Matrícula Consular. It was a massive public-consular diplomacy initiative undertaken by the Mexican consular network across the United States. The focus was on advocacy, explaining the advantages of recognizing the MCIC as a form of identification for their institutions. It resulted in establishing a direct dialogue with thousands of authorities and financial institution officers, which in many cases developed into strategic alliances or at least meaningful collaborations. The benefit for the Mexican community was dramatic and very concrete. Having a bank account opened the door of financial inclusion, which includes being eligible for certain credits and loans, facilitating and reducing the cost of wiring money home, increasing the possibility to save and invest, and bypassing the usage of money lenders and wiring services to cash paychecks and sending money. Besides, having a form of identification also allowed them to come forward as witnesses of crimes, identify themselves to the police, access medical care, have greater participation in PTA meetings, and in some states, access to driver's licenses. For Mexico´s consulates, the Matrícula Consular opened the door for the collaboration with the Federal Reserve in the Directo a Mexico program, reduced the costs of remittances, and promoted its investment in their home communities, mainly through the 3x1 matching fund's program. As an outcome of the MCIC program's tremendous success, other countries followed with their own consular ID card programs. The Matrícula program experienced significant updates in 2006 and 2014. Today it continues to be a valuable resource for the Mexican community living in the United States. In 2019, 811,951 consular ID cards were issued by consular offices north of the border, with a monthly average of 67,663. The Mexican Consular ID card program is an excellent example of public-consular diplomacy, where Mexican consulates work toward establishing partnerships with local, county and state authorities to benefit the Mexican community. The program also showcases Mexico's successful consular diplomacy and the value of engaging with local and state stakeholders in its overall foreign policy. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company.  There are only two more chapters to review of the book Mexican Consular Diplomacy in Trump´s Era, so today, I will comment on the essay written by Ambassador José Octavio Tripp titled “Mexican Consular Diplomacy and the risks of administrative hydrocephalus.” The chapter´s main point is that Mexico´s Consular Diplomacy's success in the United States has the risk of demanding too much from the consular network, developing hydrocephalus. He describes how, through the years, the consulates ´responsibilities have nearly fourth-fold, without the same amount of additional resources. As the reader will learn, this essay is the perfect description of the consular affairs modernization process that most countries have undertaken in the second part of the 20th century referred to in the work of Maaike Okano-Heijmans and Jan Melissen titled Foreign Ministries and the Rising Challenge of Consular Affairs: Cinderella in the Limelight. Additionally, it closely follows the definition of Consular Diplomacy presented by Maaike Okano-Heijmans, a scholar of the Clingendael Institute, in the paper “Change in Consular Assistance and the Emergence of Consular Diplomacy”. In his essay, Ambassador Tripp explains that the consulates could suffer from abnormal and harmful growth, similar to a brains´ hydrocephalus if they continue to expand their obligations.[i] He proposes developing a plan that evaluates what works and what does not, focusing on Mexico's foreign policy goals. In the section titled “Genesis”, Tripp explains that September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks are the origin of Mexico's Consular Diplomacy. It resulted from the end of the circular migration of Mexican due to growing immigration enforcement at the border and in the interior of the U.S.[ii] He discusses the efforts taken by the government of Mexico in its Consular ID card program, indicating that was the iconic activity of Mexico´s Consular Diplomacy at that time.[iii] Interestingly, Tripp includes a definition of Consular Diplomacy from the then Undersecretary for North America, Sergio M. Alcocer Martínez de Castro, in the introduction to the volume dedicated to Consular Diplomacy of the Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior: “public policy, that besides dealing with the traditional tasks of documentation services and protection to citizens, explores new action areas, such as the promotion of Mexico´s economic and technological interest, with the double purpose to empower Mexicans abroad and promote the national interest.”[iv] However, the Ambassador indicates that this definition is insufficient because it did not include some of its elements, such as communitarian activism and consular political-administrative management.[v] In the second part of the chapter, Tripp describes the growing consular responsibilities from the 1990s onward, indicating that they have jumped from seven traditional duties to nearly 50 overall.[vi] The Ambassador explains the development of new consular responsibilities in three major areas:

Tripp emphasizes that this list did not include all the administrative responsibilities that, even though they are not classified as services, they utilize the consulates´ limited time and resources.[viii] Afterward, he briefly describes some of the new tasks that the consulates have to perform, as seen in Figure 1 at the bottom of the post. As the consulates' duties grew, the Ambassador explains, so the media's attention to Consular Affairs. So, in a high visibility case, the consul has to deal not only with local authorities but also with multiple Mexican actors.[ix] The Ambassador identifies two essential characteristics of Mexico´s Consular Diplomacy:

Tripp identifies positive and negative consequences of the transformation of the Mexican Consular Diplomacy:

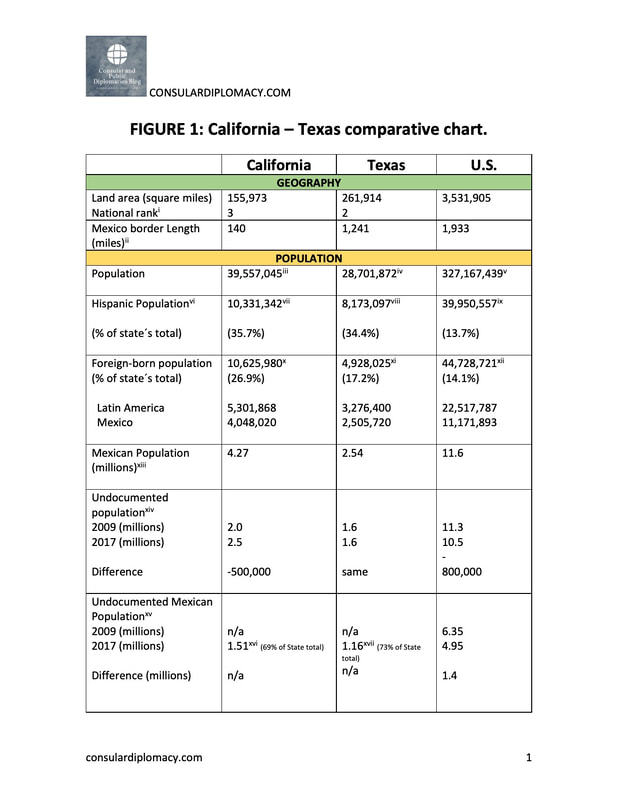

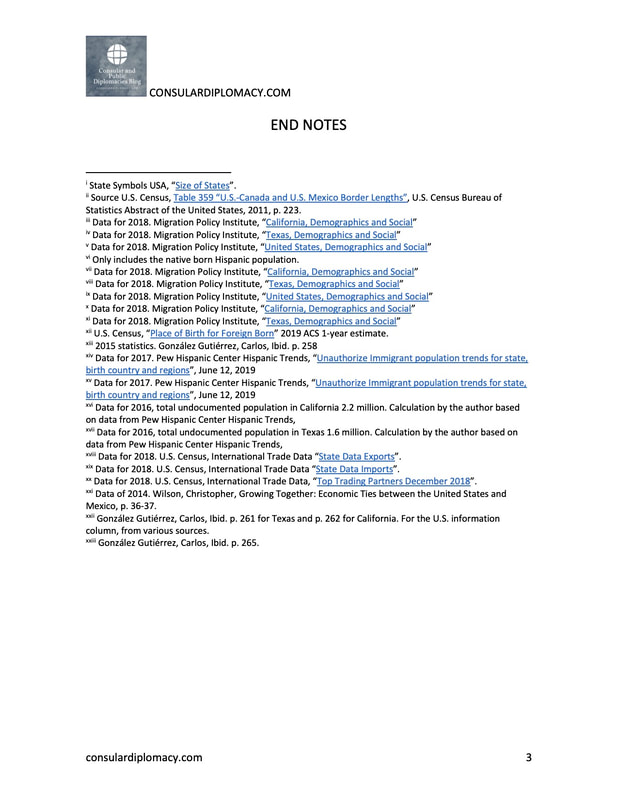

The expansion of Mexico´s international reputation, together with offering unique services to its Diaspora, indicates that Consular Diplomacy will continue to develop in the future. However, the Ambassador warns about the risks of excessively burdensome consular work.[xiii] Tripp states that it is imperative to develop a comprehensive plan that establishes the priorities and delineates its limits, so Mexico´s Consular Diplomacy can be sustainable in the long run. It is essential to limit its growth and eliminate no-priority tasks.[xiv] As part of the planning process, the Ambassador includes the need to define the consulate´s vocation or niche. For example, he distinguishes a border consulate's priorities from one located in a high tech or research region. Furthermore, he indicates the necessity of having a flexible evaluation process that focuses on the consulate's efficiencies of its main tasks.[xv] The chapter is a valuable contribution because it shows the impressive growth of consular duties and its risks. It also describes the greater weight of consular affairs in Mexico´s foreign policy and the growing interests of the media and politicians. Besides, Tripp proposes developing a plan that eliminates non-fundamental tasks and seeks to limit citizen´s expectations of consular protection and services. The Ambassador indicates that Mexico increased its reputation, not only amongst Mexicans but internationally, so he found a new source of soft power and a tool for nation-branding. Additionally, implicitly, he states other Mexican authorities' interest to have an international presence or expand its programs to cater to Mexicans abroad. Interestingly enough, the consulates have responded to the augmentation of its responsibilities successfully, although, as the Ambassador commented, it might distract resources from their fundamental obligations. I believe that they have done that efficaciously by expanding the partnerships with local and state allies. [i] Tripp, José Octavio, “La diplomacia consular mexicana y los riesgos de la hidrocefalia administrativa” en La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en Tiempos de Trump, 2018, p. 217. [ii] Ibid. p. 218. [iii] Ibid. p. 219. [iv] Ibid. p. 219. [v] Ibid. p. 219. [vi] Ibid. p. 220. [vii] Ibid. p. 220. [viii] Ibid. p. 220. [ix] Ibid. p. 226. [x] Ibid. p. 226-227. [xi] Ibid. p. 227. [xii] Ibid. p. 228. [xiii] Ibid. p. 227. [xiv] Ibid. p. 228. [xv] Ibid. p. 228-229. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company.  In this chapter of the book, Vanessa Calva Ruiz explains one of Mexico´s Public Diplomacy strategies implemented in the United States: Developing partnerships with allies and its community based on shared ideas and interactive dialogue. However, she does not use the term “Public Diplomacy” explicitly in her text. Calva Ruiz identifies the establishment of a new model of consular care as a catalysis for the expansion of networks with non-traditional groups and organizations, such as the Jewish community and LGBT associations.[i] She also indicates that the consular care new model derives from the Human Rights Constitutional amendment of 2011 that adopted the “pro-persona” principle. The new model is grounded on dialogue and trust between the Mexican community and the consular network.[ii] This new consular care model has resulted in identifying additional needs of the Mexican community, thus pushing forward the development of new partnerships, including novel allies. Calva Ruiz explains that Mexico has a reliable consular administration in the U.S. However, each of the 51 Mexican consulates operates in a unique form, considering the specific circumstances of its location and the Mexican community's characteristics.[iii] I believe this characteristic is essential due to the size and complexity of the United States' political landscape. Additionally, she describes the trípode consular or consular tripod, which comprises of the activities and programs of the three areas of consular assistance: protection to citizens, documentary services, and community affairs. The three interact to provide better services and also empower the Mexican community.[iv] As an example of the trípode consular, she presents the Ventanilla de Atención Integral para la Mujer or the “Initiative for the Comprehensive Care of Women” (VAIM) that interconnects all areas of the consulates to offer specialized assistant to Mexican women. Besides, it promotes training and sensibilization about their challenges and created a resources and services directory.[v] The expansion of the VAIM in 2016 pushed the consulates to be proactive in developing alliances with new stakeholders. Traditionally, consular offices have extended collaboration with Latino organizations, civil rights groups, and Hometown Association.[vi] But in recent years, the search for new partners. She offers as an example the activities that were developed with LGBT national associations, such as Human Rights Campaign, GLAAD, and GLSEN in the United States together with Mexico´s Consejo Nacional para la Prevención de la Discriminación (CONAPRED) and Supreme Court of Justice.[vii] As a result, consulates created “safe zones”, participated in training sessions, information campaigns, Pride and Spirit days celebrations,[viii] not only in the U.S. but also in embassies and consulates worldwide. Check out the excellent video produce by the Ministry for Spirit Day 2017 at the bottom of this post. As part of the new consular care model, Calva Ruiz also includes the use of new technologies, and describes the creation of the Centro de Información y Atención a Mexicanos (consular protection calling center) and the MiConsulmex smartphone app.[ix] I think that another example of specialized consular assistance to specific vulnerable groups is the development of three consular care protocols: -Unaccompanied migrant children and adolescents, created with the support of UNICEF Mexico.[x] -Victims of gender-based violence, with UN Women. -Victims of human trafficking, with the International Organization for Migration. Vanessa Calva Ruiz concludes that “the establishment of partnerships not only takes care of urgent needs of the Mexican community but also assist them in integrating to the host society by linking them with local actors that offer resources.”[xi] In her chapter, Calva Ruiz cites an article that she wrote and was published in The Hill newspaper, highlighting Consular Diplomacy activities in favor of the Mexican LGBT communities. You can read the articles here. “Consular Diplomacy and LGBT rights, lessons from Mexico.” This paper is worth reading because it highlights how Mexico´s Consular Diplomacy has expanded with the establishment of non-traditional allies, such as LGBT national organizations, that provide services to the Mexican community and help them integrate. To see some of inclusive flyers visit https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/475074/Infograf_as_Incluyentes_-_INGL_S_-2019.pdf [i] Calva Ruiz, Vanessa, “Diplomacia Consular y acercamiento con socios estratégicos” in La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, 2018, p. 210. [ii] Ibid. p. 206. [iii] Ibid. p. 205. [iv] Ibid. p. 208. [v] Ibid. p. 208-209. [vi] Hometown Associations or Clubes de Oriundos are community-based organizations that bring together persons from the same location. Normally, they support the organization of traditional festivities in their hometowns. [vii] Ibid. p. 211. [viii] See for example Arelis Quezada, Janet, “Consulados y embajada de México participan en #SpiritDay Mexican Consulates and Embassy participates in #SpiritDay”, GLAAD website, October 16, 2017. [ix] Ibid. p. 213-214. [x] For a brief description of the protocol´s origins and its benefits, see Gallo, Karla, “En el camino hacia la protección integral de la niñez migrante, UNICEF México Blog, August 21, 2019. [xi] Ibid. p. 215. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company.  After reviewing the TRICAMEX consular coordination program developed in South Texas, and discussing the Transborder Consular Diplomacy experience of CaliBaja between Southern California and Baja California, I think is advisable to examine the chapter written by Ambassador Carlos González Gutiérrez titled “The meaning of a special relation: Mexico´s relationship with Texas in the light of California´s experience”. Ambassador González Gutiérrez had a first-hand experience of the differences between the two giants. He was the Consul General of Mexico in Sacramento, California, and later in Austin, Texas, the two States' capitals. It is not an exaggeration to say that what happens in the Golden State and the Lone Star State has a similar impact on Mexico and its community in the U.S. as the bilateral relationship in Washington and Mexico City. These two heavy-weights were once part of Mexico, as I mentioned in my post about the Origins of Mexico´s Consular Diplomacy. For most of history, they had comparable approaches to Mexico and the Mexican community living there. However, in the 1990s, while Texas had a pragmatical approach, California´s electorate approved the ballot initiative Proposition 187 in 1994. Both States coincided in 2001, as the two enacted legislation to offer in-state tuition to undocumented persons who graduated from local high schools. But, as the reader will see in the chapter´s review, from there, their positions about immigration issues have significantly diverged. While the Golden State has promoted welcoming immigration policies, the Lone Star State has become the spearhead of the anti-immigrant movement in the U.S. Before moving forward, there is an important caveat that applies across the United States. Even though each State´s policies and the society´s attitudes towards immigrants are very different, not all is black or white, but many shades of gray, or I should say red and blue. Rural and ex-suburbs areas of the Golden State have the same negative sentiments towards immigrants as in any part of the Lone Star State. However, Texan cities such as Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio, and even border towns as El Paso and Brownsville are as welcoming to foreigners, particularly Mexicans, as California as a whole. You just have to see a county electoral map in both states to understand this situation. Figure 1 includes a comparative chart of some of the differences between the two States mentioned by Ambassador González Gutiérrez in his chapter, which will help comprehend better the situation in both States. So, let´s start with the review.

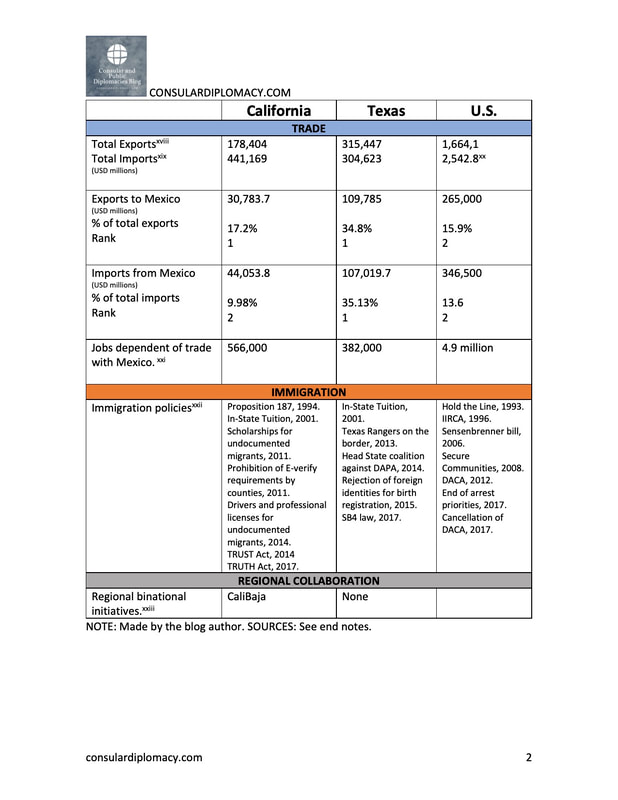

The Ambassador declares that his essay's objective is to explore the relationship between Mexico and Texas in trade and migration while comparing it with California´s links with Mexico. He also analyzes the short and long-term perspectives of the Mexican Consular Diplomacy in Texas.[i] While describing the similarities and differences of Mexico's relationships and the Golden and the Lone Star States, González Gutiérrez pinpoints the origins of the very different roads that both states have taken regarding immigration. The Ambassador indicates that “if the Latino electorate in Texas were as relevant as is in California, it is less likely that Texas would promote with the same vigor a restrictive agenda regarding immigration.”[ii] As the reader will learn, the chapter is a vital contribution to understanding different paths that both States have taken concerning their immigrant communities. The Ambassador uncovers Texas´ disassociation between the reality of the migrants' relevance to the States´ prosperity and its anti-immigrant discourse and policies.[iii] González Gutiérrez substantiates comparing Mexico´s relationship with California and Texas because they are the two largest States, and both have the closest links to our country. Besides, the two represent the opposites of the U.S. ideological spectrum and reveal very different political cultures.[iv] The Ambassador implies that California and Texas´s different immigration paths resulted from a significant increase of Hispanics in Texas (60.4%), compared to California (38.9%) from 2000 to 2015.[v] The changes in foreign-born were also dissimilar. From 1990 to 2000, the foreign-born population grew by 37.2% in the Golden State, while from 2000 to 2018, only 19.9%. The numbers are superior in the Lone Star State, so from 1990 to 2000, it increased by 90% and 2000-2018 by 70%.[vi] I think there was a similar growth of anti-immigrant attitudes in places where new immigrants arrived recently. Additionally, from 2009 to 2014, as a result of the economic crisis, the number of undocumented Mexicans fell 190,000 in the Golden State while the numbers remained the same in the Lone Star State.[vii] Afterward, González Gutiérrez describes how California and Texas responded to immigration challenges. He starts explaining that in 2001 the two legislatures approved in-state tuition for undocumented youth. For the Golden State was the beginning of several pro-immigrant bills, while in Texas, it was outlier legislation and soon turned into the anti-immigrant field.[viii] While California inaugurated the era of anti-immigrant policies with Proposition 187 in 1994, later on, after taking over the control of the legislature and the governor´s office, the State embarked on an integrative agenda for migrants, enacting several laws, such as;

Meanwhile, from a practical perspective on immigration with then-governor George W. Bush, Texas became the anti-immigrant movement forerunner in the United States with Governor Greg Abbott and the enactment of the SB4 law in 2017.[x] The Ambassador explains that this movement resulted from the total control that the Republican party has of the State´s government and the need for getting the support of hard-core primary voters.[xi] He pinpoints the move to a more radical position as a result of Governor Perry´s presidential aspirations. He was the one that first sent Texan Rangers to guard the border, arguing the failure to do so by the federal (Obama) government.[xii] In the section titled “A special relationship with Mexico?”, González Gutiérrez tries to explain Texas´ contradictory position about its southern neighbor, considering that it has a very close trade and economic relation while implementing anti-immigrant policies directed mainly against Mexicans.[xiii]- As previously mentioned, he elucidates that the elections occur in the primaries. Politicians prefer short-term gains for their support, even if this means alienating part of the Latino community or against the State´s economic interests.[xiv] The Ambassador does not think that Texas will follow California on immigration issues because labor unions in the Lone Star State are not as strong as the Golden State. Also, the political distance between the two parties in California was narrower than the one in Texas.[xv] Besides, both States' political cultures are very different, and “it would be a mistake to assume that Latinos in the two are ideological alike just because they have the same ethnicity.”[xvi] In the last part of the chapter, the Ambassador evaluates Mexico´s Consular Diplomacy in Texas. He explains that the eleven consulates of Mexico in Texas have to deal with a “cognitive dissonance”, between the excellent trade partnership and its “Mexican bashing”.[xvii] González Gutiérrez depicts the Texan business sector's effort thru the Texas Mexico Trade Coalition to defend NAFTA, while State politicians remained on the sidelines for a while. It was not until the Coalition lobbied them when they publicly supported free trade with Mexico and Canada.[xviii] He asserts that Texas's special relation is limited and has not crossed over to additional bilateral concerns. It has not developed into regional-transborder arrangements such as the links between Baja California and California in CaliBaja, or the Arizona-Mexico/Sonora-Arizona Commission.[xix] Sadly, I think, the State with the most extensive shared border “there are no fora, commissions nor periodical meeting with the authorities of the four Mexican border states.”[xx] Moreover, the Ambassador indicates that describing the situation at the border as a war zone does not help either. It is beneficial for getting funds or the signing of anti-immigrant bills. Still, it encumbers focusing on the bilateral relations' positive topics, such as economic development or the construction of binational infrastructure projects.[xxi] González Gutiérrez recommends that Mexico has to take advantage of Texas mobilization in support of NAFTA. Besides, the consulates need to assist in renewing old collaboration schemes or establishing new ones such as binational business and majors meetings.[xxii] At the same time, he declares the relevance of launching a Public Diplomacy strategy to highlight the contributions of Mexican migrants to the Lone Star State in public discussions.[xxiii] The Ambassador concludes that Mexico must cultivate a permanent dialogue with the Texas government to celebrate economic integration and be aware of the gap between reality and the public discourse.[xxiv] González Gutiérrez introduces an exciting idea that the consulate's work contributes to mitigating U.S. government institutions' absence responsible for facilitating new immigrants' integration. This idea is in line with what Francisco Javier Díaz de Léon and Víctor Peláez Millán described as the empowerment of the Mexican Community in their book´s chapter. Why is it worth reading? The chapter summarizes very well the different paths that the Golden and the Lone Star States have taken regarding immigrant issues. The Ambassador distinguishes some of the reasons this has happened, which helps comprehend the country's current situation. He also identifies areas of opportunities for Mexico´s Consular Diplomacy, particularly in closing the gap between reality and the public discourse in the Lone Star State. The Ambassador indicates that Texas offers a few advantages than other States, like its economic integration, the shared challenges at the border, and the growing Mexican population. I believe that if Mexico finds a way to work with Texas on this issue and promote greater collaboration in bilateral matters, it could lead the path to transform the current anti-immigrant attitudes and policies in other parts of the United States. To achieve this goal, I think Mexico would need to have a laser-focus Public/Consular Diplomacy long-lasting strategy, with a specific component that targets rural communities across the Lone Star State. It is interesting to reflect that the Consular Diplomacy of a country is the paradiplomacy of the other country´s State and local authorities. In this regard, this chapter contributes to the concept of Consular Diplomacy by incorporating the idea of paradiplomacy into its frame. Most of the consulates diplomatic activities are targeted toward state and local audiences. Of course, it has to consider the national context and the overall bilateral relation to be successful. By scrutinizing California and Texas trade and immigration stances and Mexico´s strategy, Ambassador González Gutiérrez encompasses paradiplomacy into Consular Diplomacy. This notion is relevant as both ideas are the different sides of the same coin. I also think that Mexico´s Consular Diplomacy in the United States had to adapt to the country´s patchwork of multiple, sometimes significantly different, federal, state, county, and authorities and policies. In the chapter, California and Texas's example proves very useful to see this characteristic and the need to have a flexible Consular Diplomacy. [i] González Gutiérrez, Carlos, “El significado de una relación especial: Las relaciones de México con Texas a la luz de su experiencia en California” in La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en Tiempos de Trump, 2018, p. 254. [ii] Ibid. p. 255. [iii] Ibid. p. 264. [iv] Ibid. p. 254. [v] Ibid. p. 259. [vi] Migration Policy Institute, “California, Demographics and Social” and “Texas, Demographics and Social” [vii] Ibid. p. 258. [viii] Ibid. p. 259-262. [ix] Ibid. p. 262. [x] Ibid. p. 261. [xi] Ibid. p. 263. [xii] Ibid. p. 260-261. [xiii] Ibid. p. 262-264. [xiv] Ibid. p. 263. [xv] Ibid. p. 263. [xvi] Ibid. p. 263-264. [xvii] Ibid. p. 264. [xviii] Ibid. p. 264. [xix] The official name in English is Arizona-Mexico Commission, while in Spanish is the Comisión Sonora-Arizona. [xx] González Gutiérrez, Carlos, Ibid. p. 265. [xxi] Ibid. p. 265. [xxii] Ibid. p. 265. [xxiii] Ibid. p. 265. [xxiv] Ibid. p. 265. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer, or company.  In this post, I will review the last chapter of the book "The role of Consular Diplomacy in a transborder context: The case of CaliBaja", written by Ambassador Marcela Celorio. Note: I will use the term CaliBaja as presented in this chapter, e.g. CaliBaja rather than Cali Baja or Calibaja. I am skipping a few chapters because I believe the CaliBaja example is the other side of the coin of the TRICAMEX mechanism that I reviewed in this post. In this chapter, Celorio puts forward a very different experience from the other corner of the Mexico – U.S. Border: CaliBaja, a bi-national mega-region, which stands for California-Baja California. The Ambassador also discussed an example of what she defines as Transborder Consular Diplomacy. The CaliBaja initiative started in 2006-2007 and was officially launched in 2011. It comprises local and county authorities along the border between the two states but is mainly focused on the Tijuana-San Diego axis. There is even a website about the mega-region calibaja.net. It is the most-advance bilateral collaboration scheme along the nearly 2,000 miles of the shared border. As seen in the previous review, TRICAMEX comprises four consulates, focusing on immigration issues. At the same time, CaliBaja is a business-lead scheme that concentrates on trade and economic development. Ambassador Celorio divided the chapter into three: