|

This post is dedicated to all individuals and institutions participating in the IME's activities and programs through its 20-year history. On Sunday, April 16, the Institute of Mexicans Abroad (Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior) celebrated its 20th anniversary. On that day in 2003, the government of Mexico published the Decreet that established this new diaspora engagement institution in the Federal Registry. The Institute, also known as the IME (for its acronym in Spanish), revolutionized the relationships between the government of Mexico (especially the executive branch of the federal government) and the Mexican community in the United States and Canada. For the first time in history, Mexican migrants and second-generation and National Hispanic organizations sat at the table by participating in the IME's Advisory Council (known as the Consejo Consultivo del IME or CCIME). The IME also profoundly transmuted the role of the consulates and hometown associations in their host municipalities and states, engaging with a wide variety of actors from businesses and local authorities to civil society organizations and institutions. They developed effective and long-lasting partnerships to cater to the needs of the Mexican community in North America. Their activities can be classified as a successful public diplomacy effort (Márquez Lartigue, 2023). Background Even though migration to the United States has been a constant in some states in Mexico for over a century, significant changes dramatically transformed the situation in the late 1980s and through the 1990s. The combination of several factors metamorphosed Mexican migrants from temporary workers into a permanent diaspora:

Besides, the government of Mexico reformed its consular system, including the establishment of the Program of Mexican Communities Abroad in 1990, expanded its consular network, and granted greater autonomy to consular officers to actively engage with Mexican community leaders, local and state authorities, and civil society organizations (González Gutiérrez, 1997). Government officials encouraged the establishment of Hometown Associations and confederations among migrants and Migrants Care Offices (Oficinas de Atención a Migrantes) by Mexican provincial and even municipal authorities. After the failure to negotiate a migration accord with the U.S. in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, the government of Mexico created the National Council for Mexican Communities Abroad in the summer of 2002. One of the council's tasks was to receive recommendations from consultative mechanisms (Diario Oficial de la Federación, 2002). The establishment of the IME In the autumn of 2002, Mexican consulates across the United States and Canada invited migrant community leaders to participate in the selection process of an advisory board that was going to be established as part of the IME. Ayón (2006) explains that the IME was added to traditional consular programs such as documentary services (passports, notary public, and visas) and assistance to distressed citizens because the Institute could "plan, handle, propose, and pursue national and binational strategic goals and respond to the challenges that transcend the consular district" (p. 132). IME's first Executive Director indicated that the institute had three primary functions: information dissemination, empowerment of the communities, and provision of innovative new services that go beyond regular consular programs (González Gutiérrez, 2009). Regarding information distribution, the IME had three major programs:

The consular network began offering social services through partnerships with non-governmental organizations, authorities, and even businesses. These services centered on non-traditional areas such as education (Plazas Comunitarias -Basic Adult Education- program, scholarships -IME Becas-, and exchange of teachers, among others), health (centered around the Ventanillas de Salud or Health Desks and the Binational Health Week); financial education and investment of remittances (Financial Advisory Desk -Ventanilla de Asesoría Financiera-, the Three-for-one program, and Directo a Mexico. The most important task was the empowerment of the Mexican community through the CCIME and participation in the information and services agendas (Ayón 2006, p. 132). In many ways, the government of Mexico, through its consular network, was already working on most of these programs before the creation of the IME. Notwithstanding, the key innovative aspect of the institute was its advisory council. For the first time, its approximately 120 members from across the U.S. and Canada gathered at least twice a year to prepare recommendations about policies directed at Mexican migrants in North America. The first director of the Institute, Don Cándido Morales, was also a migrant from Oaxaca living In California. Even though the CCIME had limited responsibilities centered on presenting non-binding recommendations, it provided a national platform for migrant leaders. On the one hand, they meet and engage each other, strengthening their advocacy and organization skills. It was an executive leadership training academy (Ayón, 2006, p. 135). On the other hand, it opened the doors to authorities on both sides of the border at all levels. It facilitated their engagement with civil society and, for some, in political activities. Giving Mexican migrants a voice and visibility through the CCIME was helpful as it helped expand many of the IME programs, such as the Health Desks and the creation of IME Becas. Also, many board members advocated enacting the overseas absentee vote implementing law in 2005 and the migrant demonstrations of the Spring of 2006. The IME has evolved thought its 20 years of existence, but most of its core functions continue to this day. In 2022, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs launched the 2022-2024 Action Plan for Mexicans living overseas, which contains nearly 40 activities. IME's successful public diplomacy Without using the term public diplomacy, the IME's activities can be defined as such. Its programs encompass Professor Nicholas Cull's (2019) five elements of public diplomacy listening, advocacy, cultural activities, and educational exchanges. Even there was some international broadcasting in the form of electronic information bulletins. Interestingly, the target audiences were migrants themselves. However, it did not stop there; through its many undertakings, consular offices engaged with all sorts of people and organizations and slowly built long-lasting partnerships. Thus, nowadays, the IME "has about 2,000 partners in Mexico and the USA" (Mendoza Sánchez & Cespedes Cantú, 2021). Another contribution of the IME was that many countries, from Uruguay to Morocco and Türkiye to Colombia, requested meetings and attended some of its activities to learn more about the country's diaspora engagement programs. (Laglagaron, 2010, p. 39; Délano, 2014). The IME generated soft power for Mexico's diplomacy soft power, as it attracted attention around the globe. It has also generated consular partnerships with other Latin American consulates in programs like Binational Health Week and Labor Rights Week that are celebrated across the U.S. every year. With the countries of the Northern Triangle of Central America, several consulates established consular coordination schemes known as Tricamex. One of the most outstanding achievements of the IME was reducing the barriers between the government and the migrants. After years of hard work, little by little, it has gained the community's trust, which was very little. Significant investments in the modernization of documentary services have also resulted in better quality services. The Institute also gave way to the rise of Mexico's public-consular diplomacy. To learn more about its origins and features, read my practitioner's essay in the Journal of Public Diplomacy titled Beyond Traditional Boundaries: The Origins and Features of the Public-Consular Diplomacy of Mexico. References Ayón, D.R. (2006). La política mexicana y la movilización de los migrantes en Estdos Unidos. In Carlos Gónzalez Gutiérrez (coor.), Relaciones Estado-diáspora: La perspectiva de América Latina y el Caribe. Tomo II, (pp. 113-144). Ciudad de México. Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. Cull, N. J. (2019). Public Diplomacy: Foundations for Global Engagement in the Digital Age. (Kindle Edition). Délano, A. (2014). The diffusion of diaspora engagement policies: A Latin American agenda. Political Geography, 41, 90-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2013.11.007. Diario Oficial de la Federación. (2002, August 8). Acuerdo por el que se crea el Consejo Nacional para las Comunidades Mexicanas en el Exterior. https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=721574&fecha=08/08/2002#gsc.tab=0 Diario Oficial de la Federación. (2003, April 16). Decreto por el que se crea el Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior, con el carácter de órgano administrativo desconcentrado de la Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. https://www.gob.mx/ime/documentos/decreto-por-el-que-se-crea-el-ime González Gutiérrez, C. (1997). Decentralized Diplomacy: The Role of Consular Offices in Mexico´s Relations with its Diaspora. In Rodolfo O de la Garza and Jesús Velasco (eds.), Bridging the Border: Transforming Mexico-U.S. Relations, (pp. 49-67). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. González Gutiérrez, C. (2006). Introduccion: El papel de los gobiernos. In Carlos Gónzalez Gutiérrez (coor.), Relaciones Estado-diáspora: La perspectiva de América Latina y el Caribe. Tomo II, (pp. 13-42). Ciudad de México. Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. González Gutiérrez, C. (2009). The Institute of Mexicans Abroad: An Effort to Empower the Diaspora. In Dovelyn Rannverg Agunias (ed.), Closing the Distance: How Governments Strengthen ties with their Diasporas, (pp. 87-98). Washington, DC. Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/closing-distance-how-governments-strengthen-ties-their-diasporas Laglagaron, L. (2010). Protection through Integration: The Mexican Government's Efforts to Aid Migrants in the United States. Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/IME_FINAL.pdf Márquez Lartigue, R. (2023). Engaging migrants in the Mexico-US diplomatic relationship: The Institute of Mexicans Abroad. Working paper presented in the ISA 2023 convention. Unpublished. Mendoza Sánchez, J. C., & Cespedes Cantú, A. (2021). Innovating through Engagement: Mexico’s Model to Support Its Diaspora. In L. Kennedy (ed), Routledge International Handbook of Diaspora Diplomacy (Kindle Edition). Routledge. Terrazas, A. and Papademetriou, D. G. (2010). Reflexiones sobre el compromiso de México con Estados Unidos en materia de migración con énfasis en los programas para la comunidad de mexicanos en el exterior. In Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores, Mexicanos en el Exterior: Trayectorias y Perspectivas (1990-2010), (pp. 107-139). Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores, Instituto Matías Romero. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company.

0 Comments

Maribel (not her real name) went with her family to a Mexican consulate in the U.S. She was there to get a health referral to have a free mammogram at the local health clinic. Besides, her youngest kid, Jaime, needed eyeglasses, so she got a voucher for free prescription glasses from a well-known grocery store. On the same visit, Eduardo, a Guatemalan citizen and Maribel's partner received screenings for blood glucose and blood pressure. All these services were provided by the Ventanilla de Salud program (VDS -Health Desk/Window-)[i], a public-consular diplomacy effort that will celebrate its 20th anniversary next year. Since its creation as a pilot program in Southern California in 2003, the VDS at the Mexican consulates (and mobile units) has provided more than 45.8 million health-related services to 18.3 million people. Its services are not exclusively for Mexicans, so many more people, including U.S. citizens, have benefited from this effort. The VDS does not solve all the health-related barriers and issues faced by the Mexican migrants in the U.S.; however, it certainly alleviates some of their anguish and distress. Background. The primary motivation behind establishing the VDS is the unequal access to health services in the U.S. by Hispanics in general and undocumented migrants in particular, even after the enactment of the Affordable Care Act of 2010. In 2016, 24 million persons did not have health insurance, and the percentage of Hispanics uninsured of the total grew from 29% in 2013 to 40%. In 2019, two out of five Mexican migrants did not have insurance (38%), “compared to 20% of all immigrants and 8% of the U.S. born.”[ii] Two years later, the percentage of uninsured Mexican migrants diminished by 1% to reach 37% in 2021.[iii] In the United States, an uninsured person typically pays full price for medical expenses, while an insured individual will receive negotiated discounts from their insurance, so the cost drops dramatically. The passing of Proposition 187 in California in 1994 significantly impacted the Hispanic community, not only the undocumented Mexican population, although it never came into force.[iv] Most migrants stayed away from medical services due to the fear of being taken away by immigration authorities and the confusion regarding immigration’s public charge, particularly during the Trump Administration.[v] Besides, the creation of the Binational Health Week in 2001 by the government of Mexico and the Health Initiative of the Americas (HIA) gave a big push for establishing a permanent health office at the Mexican consulates that could also provide information year-round (Link to the blog post about the Binational Health Week). However, it was not that easy, as the VDS required having non-official personnel inside the consulate. Raúl Necochea López details the difficulties that had to be overcome to open the Health Desks in the consulates´ offices, as it was “a significant departure from the established restrictive norms about the use of consular resources,”[vi] The biggest issue was the permanent presence of non-consulate personnel at the consular premises. After some time, finally, in February 2002, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Mexico accepted the idea, and a pilot program proposal was developed. In 2003, the Consulates of Mexico in San Diego and Los Angeles opened the first VDS as a pilot project. After their initial success, the Ministry of Health of Mexico has provided funds for the program since 2006. Taking advantage of the hundreds of persons that visit the consulates every day was a determining factor for the health institutions in establishing a permanent health office at the consular premises. It provided access to hard-to-reach populations in a secure and culturally appropriate environment. “A key factor in the [partner organizations’] ability to reach this population is the fact that the consulate is generally considered a trustworthy space in the sense that a person´s migration status will not be at risk.”[vii] What is the Health Window? The VDS is a designed space inside the consulate, generally in the public waiting area, attended by personnel of the local partner. The Health Desk provides health-related information and personalized counseling, makes referrals to a health clinic and other specialized services, and offers the opportunity to receive different types of screening. “The VDS program is a multistrategy approach to providing personalized assistance and outreach to Mexican immigrants unfamiliar with the U.S. health system.”[viii] The Health Desk program is a public-private partnership with the participation of Mexico´s Ministry of Health (providing funding and overseeing the program), the Institute of Mexicans Abroad (IME) through the consular network, and local government and non-government health care organizations, such as community health centers, hospitals, universities, migrant-serving institutions, and pharmacies. The local partners provide human and financial resources and knowledge, while the consulates offer a space for their activities. “The aim of this initiative is to build a network of informational windows [Health Desks] to increase knowledge about health and access to services for Mexican migrants and their families residing in the United States.”[ix] The VDS provides the following general services, which vary depending on several issues, most notably the available local resource and existing partnerships:

As the program evolved, more organizations began offering health-related services, from a wide variety of screenings and immunizations to access to quitting smoking programs and referrals to community health clinics. In 2015, the VDS served 1,525,504 persons who received 415,509 screening and 63,084 vaccinations.[xi] The VDS provided a wide variety of information, including health insurance, domestic violence, hypertension, diabetes, substance abuse, obesity, birth control, and mental and women´s health, among other topics.[xii] The evolution of the Heath Desk. After its initial success, the VDS expanded rapidly like other successful consular programs. Eleven consulates established Health Windows between 2004 and 2007. And, from 2008 to 2011, an “additional 38 VDS opened for a total of 50 affiliated with the Mexican consulates that work closely and in partnership with local health-care organizations.”[xiii] Two circumstances helped in the fast expansion of the program. The first one was the creation of a health commission of the Institute of Mexicans Abroad´s Advisory Council -CCIME- in 2003. The advisory council was the first of its type in the government of Mexico.[xiv] The second situation was the increase in the reunification of women and children in the U.S.,[xv] significantly changing the demographics and needs of the Mexican migrant community. Health care has become increasingly critical for new migrant families. For example, in 2013, women were 63% of the people served by the VDS.[xvi] An additional advantage of the Health Desk was that the IME organized several Jornadas Informativas (specific topic conferences) centered on health issues. It later created a special meeting of all VDS partner organizations, which was unique to the program. In December 2020, the 17th Annual meeting of the Health Desk program took place online due to the pandemic. In 2012, a Health Advisory Board was established with nine members to define the priorities of the VDS and make recommendations to promote the program´s sustainability. The board was one of the first to be established to strengthen the programs implemented by the IME. During the Covid-19 pandemic, the VDS played a crucial role in providing information to the community via social media and other forms of communication. In 2021, Mexico´s consular network in the United States helped provide 80,000 COVID-19 vaccines[xvii] not only to the Mexican community but also to Hispanics and from other countries. Through the years, the VDS has continued to evolve. For example:

The results of the Heath Desk. From 2003 until August 2022, the VDS served 18.3 million persons and offered 45.8 million health-related services, as described in Table 1, with the collaboration of around 600 local partners. Table 1. Ventanilla de Salud Program: persons serviced, and health-related services provided from 2003 to 2022 Period Persons Services 2003-2017 10 million* 18.4 million** September 2017-August 2018 1.5 million 5.8 million January-July 2019 700,000 1.8 million September 2019-August 2020 2.0 million 6.0 million September 2020-August 2021 3.0 million 8.5 million September 2020-August 2022 1.1 million 5.3 million TOTAL 18.3 million 45.8 million Note: A single person can receive multiple services. According to the Institute of Mexican Abroad, between 2003 and 2019, the VDS served 22 million persons who received 8 million health-related services. Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior (2021). Ventanillas de Salud (VDS). 21 November. Sources: *2003-2017. Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior, 2017. Las Ventanillas de Salud reciben el premio de la OEA a la Innovación para la Gestión Pública. Boletín Especial Lazos. 11 October. **The number of services only includes from 2012 to 2016. Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior, 2018. Resultados Programa VDS. 26 November 2016; updated March 2018. 09/2017-08/2018: Sexto Informe de Labores, SRE. 2018, p. 190; 01-07/2019; Primer Informe de Labores, SRE. 2019, p. 136; 09/2019-08/2020: Segundo Informe de Labores, SRE. 2020, p. 157; 09/2020-8/2021: Tercer Informe de Labores, SRE. 2021, p. 145; 09/2021-08/2022: Cuarto Informe de Labores, SRE. 2022, p. 142. The impact of the VDS is more significant considering that health issues affect the family on both sides of the border, as illnesses and other health problems can result in a reduction of income and an increase in expenses. Besides reaching out to millions of Mexicans in the U.S. through the VDS program, the consulates of Mexico have established long-term alliances with a wide range of health-related organizations, such as the American Cancer Society, the National Institute for Health, Georgia Lighthouse Foundation, and Emery University´s Rollins School of Public Health.[xviii] The program has also strengthened its collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Alliance for Hispanic Health.[xix] Recognizing the great benefits that the VDS provided, in 2017, the Organization of American States granted the “Inter-American Award on Innovation for Effective Public Management” in the Social Inclusion Innovation category.[xx] The opening of the VDS was a defining moment in Mexico´s public-consular diplomacy, as it allowed, for the first time, the permanent presence of community health organizations personnel inside the consular premises. Shortly after, other groupings, such as the banking and financial sectors, assigned people to the local consulate. Various consulates also opened new specific-purpose windows focused on educational opportunities and financial education. More recently, some three consulates have created new desks to provide specialized care to indigenous migrants. Conclusions. The Ventanilla de Salud or Health Desk program is another example of an innovative public-consular diplomacy of Mexico, working as a bridge between the Mexican community living in the U.S. and its network of health partners. Health referrals and screenings are not typical consular assistance programs. However, the VDS was a groundbreaking way for the government of Mexico, together with local partners, to care for the needs of the Mexican community in a country without universal health care. The VDS also initiated the consulates' transformation into community centers. The VDS helps the Mexican community in the U.S. to alleviate their barriers to accessing healthcare and solving health-related issues. A visit to a Health Window in a Mexican consulate can be a life-changing event or at least an opportunity to learn how to navigate the U.S. health system. [i] Other translations of the VDS program are Health Stations or Health Windows. Here it Desk and Window will be used. [ii] Israel, E. and Batalova, J. 2020. Mexican Migrants in the United States. Migration Policy Institute. 5 November. [iii] Rosenbloom, R. and Batalova, J. 2022. Mexican Immigrants in the United States. Migration Policy Institute 13 October. [iv] Márquez Lartigue, R. 2022. Public-consular Diplomacy that heals: The Binational Health Week Program. Blog about Consular and Public Diplomacies. 5 March. [v] Marina Valle, V., Gandoy Vázquez, W. L., and Valenzuela Moreno, K. A. 2020. Ventanillas de Salud: Defeating challenges in healthcare access for Mexican immigrants in the United States. Estudios Fronterizos, 21. July. [vi] Necochea López, R. 2018. Mexico´s health diplomacy and the Ventanilla de Salud program. Latino Studies (16), p. 483. [vii] Délano Alonso, A. 2018. From Here and There: Diaspora Policies, Integration and Social Rights beyond Borders, p. 78. [viii] González Gutiérrez, C. 2009. The Institute of Mexicans Abroad, An Effort to Empower the Diaspora. In D. R. Agunias (Ed.) Closing the Distance. How Governments Strengthen ties with their Diaspora, p. 94. [ix] Dávila Chávez, H. 2014. Comprehensive Health Care Strategy for Migrants. Voices of Mexico. Num. 98, Winter, p. 96. [x] Secretaría de Salud and Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. 2019. Strategy: Ventanillas de Salud, p. 7. [xi] Rangel Gómez, M. G., et. al. 2016. Ventanillas de Salud: A Program Designed to Improve the Health of Mexican Immigrants Living in the United States. Migración y Salud, p. 100. [xii] Rangel Gómez, M. G., et al. 2017. Ventanillas de Salud: A Collaborative and Binational Health Access and Preventive Care Program. Frontier in Public Health. 30 June. [xiii] Rangel Gómez, M. G., et al. 2017. Ventanillas de Salud: A Collaborative and Binational Health Access and Preventive Care Program. Frontier in Public Health. p. 3. 30 June.[xiv] Délano, A. 2009. From Limited to Active Engagement: Mexico’s Emigration Policies from a Foreign Policy Perspective. International Migration Review, 43(4), p. 791. [xv] Durand, J., Massey, D. S. & Parrado, E. A. 1999. The New Era of Mexican Migration to the United States. The Journal of American History, 86(2), p. 525-527. [xvi] Rangel Gómez, M. G., et al. 2017. Ventanillas de Salud: A Collaborative and Binational Health Access and Preventive Care Program. Frontier in Public Health, p. 2. 30 June. [xvii] Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. 2021. Tercer Informe de Labores, SRE, p. 146. [xviii] Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior 2018. Alianzas Estratégicas. Published 24 November 2016; updated March 2018. [xix] Dávila Chávez, H. 2014. Comprehensive Health Care Strategy for Migrants. Voices of Mexico. Num. 98, Winter, p. 98. [xx] Organización de Estados Americanos. 2017. V Premio Interamericano a la Innovación para la Gestión Pública Efectiva 2017. Acta Final de Evaluaciones. Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior. 2017. Las Ventanillas de Salud reciben el premio de la OEA a la Innovación para la Gestión Pública. Boletín Especial Lazos. 11 October. Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior. 2017. La OEA hace entrega de Premio Interamericano a las Ventanillas de Salud. Press Bulletin. 19 December. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company.  It was mid-morning in a church in Minneapolis when Maria (not her real name) had her glucose checked as part of the Binational Health Week activities. She was in her mid-forties, and it was the first time she had done it. When the nurse saw the results, she immediately called the doctor. Maria´s sugar levels were sky-high, and she was referred to a local hospital. After three days, Maria was released from the hospital with a diabetes diagnosis. She was unaware of her illness, and her participation in the health fair might have saved her life. This situation is a common occurrence during the yearly celebration of the Binational Health Week (BHW), which is organized by the government of Mexico, through its consular network in the United States, together with the Health Initiative of the Americas, and thousands of allies across the nation, including consular offices of other countries. The program is an outstanding example of Mexico's public-consular diplomacy in the United States focused on preventive health. The BHW has reached millions of people in the 21 years since its creation. It has also promoted the establishment of multiple long-term partnerships, a defining element of 21st-century public diplomacy. Preventive health care is an extraordinary consular assistance program offered by a few countries to its citizens abroad. The BHW was developed to meet the needs of the Mexican community in the United States, a country that has struggled to provide affordable health services to all its population. Besides, the program has promoted a continuous dialogue between health authorities, organizations, and the consular network with immigrant communities. It also encouraged the creation of the Ventanilla de Salud, or Health Desk program, which will be reviewed in another post. The beginning of the Binational Health Week. Since the early 1990s, the Ministry of Health of Mexico has organized yearly multiple health weeks across the nation. During that decade, the Mexican population in the US grew rapidly due to the combination of various factors:

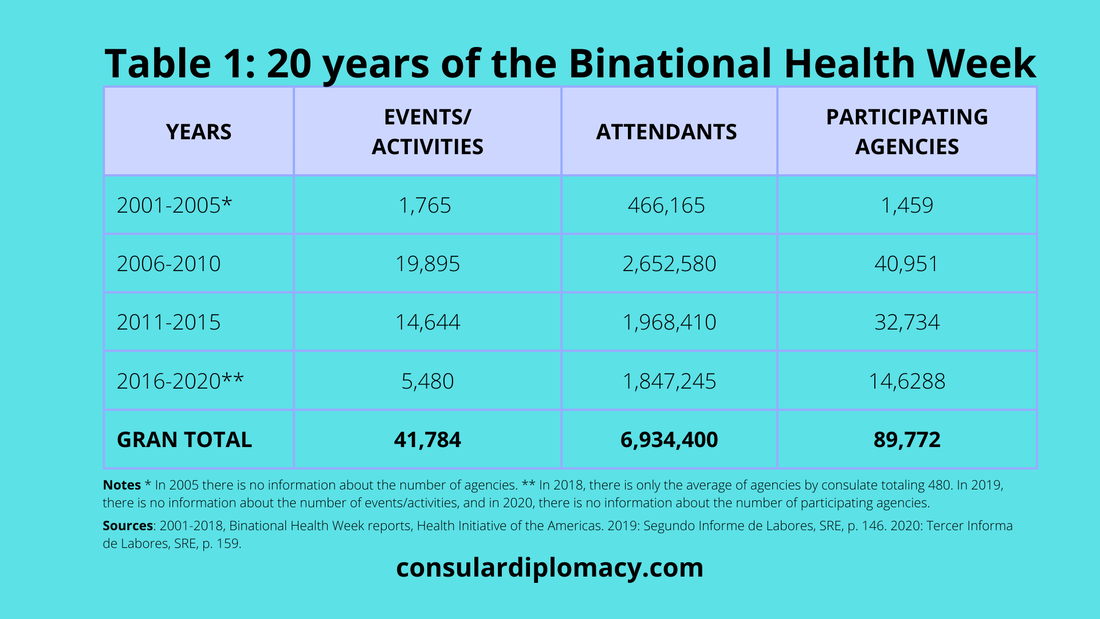

A significant development was the growing number of Mexican women and children moving to the United States, thus demanding new services such as health and education. In California, a significant push for starting the BHW was the passage in 1994 of Proposition 187, “a ballot initiative proposed by anti-immigrant organizations, which restricted undocumented immigrants from the state’s public services, including access to public education and healthcare.” It never came into force but was a hard lesson for the Hispanic community as a whole, not just the Mexican undocumented population in the state. In 2001, the then California-Mexico Health Initiative, now known as the Health Initiative of the Americas (HIA), and the government of Mexico agreed to organize health prevention activities in California in October; thus, the Binational Health Week was born. It started in seven counties, had 98 events and 115 participating agencies, and reached close to 19,000 people. The collaboration between health authorities and related organizations with the consular network deepened through the years, evolving into strategic partnerships across the nation. The evolution of the Binational Health Week, From its humble beginnings in California, the BHW took off like a rocket. It rapidly expanded to other states and, by 2004, it became a national endeavor. The then newly created Institute of Mexican Abroad (IME) and its Advisory Council supported expanding its activities to all the consulates. It was clear that access to health was an important issue, particularly for the new arrival, which comprises a large percentage of women and children, as they reunited with their families in the US due to the end of circular migration of mostly male migrants. Two critical elements of the BHW stand out, which were necessary for its success. One was that opening and closing ceremonies took place alternatively in Mexico and the US, thus making it a genuinely bilateral collaboration. The second element was that it included research activities focused on Hispanic and Mexican health through the celebration of the Binational Public Policy Forum on Migration and Health. The collaboration evolved into a partnership called Research Programs on Migration and Health (PIMSA for its Spanish acronym) that has published significant findings on the subject. Also, since 2008, Mexico´s National Population Council and the HIA have published the Migration and Health reports. The government of Mexico allocated money as seed funding for the organization of the BHW activities. It also invested much time and human capital in the organization, thus demonstrating its commitment to promote preventive health activities. In the beginning, the activities of the BHW concentrated on health fairs. Still, as the program evolved, the organizers incorporated many other services and activities with the support of the Health Desks. For example, according to the 2018 BHW report, 45% of the events were health fairs while 26% were informative sessions, 15% training, and workshops, and 6% conferences and forums. Regarding services, 33% were guidances, 22% screenings, 19% services referrals, 12% medical examinations, and 9% diagnoses. The results of the Binational Health Week. In the 20 years since its creation, 6.9 million people have attended an activity in the framework of the BHW. Nearly 90,000 agencies have participated in more than 40,000 events and activities (see table 1). Besides, the program has been very successful, from lead testing to national events and research projects. For example, from 2003 to 2018, PIMSA sponsored 116 binational research teams and 46 graduate students investing 4.4 million dollars plus over $5 million in additional funding. As mentioned before, it was in the framework of the BHW that the Ventanilla de Salud or Health Desk was developed, being another successful effort of Mexico's public-consular diplomacy. The collaboration between health authorities and related organizations with the consular network deepened through the years, evolving into strategic partnerships across the nation. Working at the Consulate of Mexico in Boston, I had to coordinate the celebration of the first Hispanic health fair in Nashua, New Hampshire, as part of the BHW activities. It was not an easy task, but once the local health authorities understood the idea behind the program, they were thoroughly committed. And it opened the door to more significant interactions between the Mexican community and the city´s residents and authorities. In conclusion, the Binational Health Week is an excellent example of Mexico´s public-consular diplomacy efforts that have benefited close to 7 million people since its creation in 2001 while establishing enduring partnerships. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company. The people of every nation have the right to decide their government, self-determination, and non-intervention. The borders of states must be respected. #StandwithUkraine.  A couple of weeks ago, Mexico´s consular network in the United States, together with federal and state labor authorities, unions, community associations, and seven other consulates, successfully organized the 13th edition of the Labor Rights Week (LRW). The LRW “is a joint initiative between the governments of the US and Mexico that seeks to increase awareness in Mexican and Latino communities about the rights of workers and the resources available to them.”[1] As the reader will learn, it started in 2009. In 2021, the 50 Mexican consulates and 560 partners held 680 events with 520,000 persons and collaborated with the consulates of Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Peru.[2] Besides, the Embassy of Mexico in Washington renewed national cooperation agreements with the Wage and Hour Division (WHS), the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), and the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). The Mexican consulates also updated 58 local collaboration agreements.[3] The significant results of the LRW amid the Covid-19 pandemic confirm that it is an example of an accomplished public-consular diplomacy initiative executed by Mexico and its network of allies in the United States. This effort adds to the successful public-consular diplomatic effort by Mexico is its Consular ID card program. However, the consular protection of Mexican workers in the United States has been a priority of the consular network since the 19th century.[4] In the third decade of the 21st century, it continues to be the focus of Mexico´s public-consular diplomacy. In the case of consular assistance in incidents of labor rights violation, Mexico developed the LRW, a successful model of collaboration where the host country authorities cooperate with the consular network to promote the rights available to all workers regardless of their immigration status. How this initiative started? The origins of Labor Rights Week After the failure to reach an immigration agreement between Mexico and the U.S., also known as “the whole enchilada”, partly due to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, both governments searched for opportunities for greater collaboration in new areas. One such field was labor rights. An alternative reason for the greater attention to labor issues by the government of Mexico is proposed by Xóchitl Bada and Shannon Gleeson. They state that it was the pressure from Mexican community groups to have a proactive role in labor rights cases that resulted in greater collaboration with U.S. authorities.[5] As a result, in 2004, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Mexico (SRE) and the Secretary of Labor issued a joint declaration followed by signing letters of intent with WHS and OSHA. The statement was renewed in 2010 and 2014.[6] After a few years of collaborating, in 2009, the SRE launched the first LRW, using the Binational Health Week as inspiration. In its first edition, fifteen consulates and 255 allies organized 199 events, with 18,788 persons. In total, 829 consular labor cases were registered.[7] Since then, Mexico´s consulates across the U.S. have entered into more than 400 agreements with regional offices of labor agencies, including OSHA, WHD, EEOC, and others (see table 1). The evolution of the LRW As with other consular assistance programs, after the successful first experience, all Mexican consulates were involved in organizing events around the LWR. During the week around Labor Day in the U.S., which is celebrated on the first Monday of September, Consulates and allies organize a wide variety of activities, from training at the consulate offices and workplaces such as canning factories and vegetable fields to individual consultations with labor lawyers, labor rights organizations, and unions. As the collaboration expanded, the Embassy of Mexico in Washington signed agreements with the NLRB in 2013, the EEOC in 2014, and the Justice Department's Office of Special Counsel for Immigration-Related Unfair Employment Practices (OSC) in 2016. In many instances, the consular network replicated these deals with the agencies' regional offices, especially with the EEOC. As part of this initiative, the SRE signed an agreement with the United Farm Workers in November 2019, the first of its type with a labor organization in the United States. The Results of the LRW Organizing a week of events focusing on labor rights has been very successful. More than 1.7 million persons have attended an event since 2009, including half a million this year alone, as the reader can see in table 1, at the bottom of the post. Regardless of the political discourse, continuity of the effort has been crucial, creating trust among the consulates and labor authorities with workers, unions, and labor rights organizations. Besides, an additional advantage is that new activities are proposed by consulates and partners every year, expanding and deepening the cooperation. For example, after a few years of the LRW, some consulates, with the help of their allies, offered workshops at different workplaces, including factories, restaurants, construction sites, and agricultural fields. They found out, though practice, that it was a lot easier to reach out to workers at their locations rather than asking them to go to a consulate or a church. The LRW has been identified as an example of “practical joint initiatives” to protect the labor rights of low-skilled immigrant workers.[8] Mexico promoted the LRW in the 2nd Global Consular Forum meeting held in Mexico in 2015, and some scholars have noted the success and some of its deficiencies.[9] It is well known that current public diplomacy strategies search to establish a long-term partnership between the receiving and the sending state. Therefore, the institutionalization of relationships with partners, through signing collaboration agreements and other forms, has demonstrated its usefulness in weathering changes of leaders and priorities of the different governments. It also has facilitated the continuity of the LRW, which has been vital to building lasting and successful relationships with allies and the workers themselves. Nina Græger y Halvard Leira state that “the degree of [consular] care provided for citizens abroad is thus tied not only to political system, but also to the state capacity, the perceived necessity for domestic legitimacy and responsiveness of foreign host governments.”[10] In the case of the LRW, the interest of the Department of Labor and other authorities in promoting labor rights in the immigrant community, through collaboration with the Mexican consular network, has been essential in its success. One of the most important results is turning the consulate into a trusted ally of local organizations and bridging them and the federal and state agencies.[11] In a country such as the US that offers fewer protections for workers and has multiple labor regulations and authorities, the LRW is an excellent public-consular diplomacy effort with a focus on some of the most vulnerable workers. It is also a perfect example of the collaboration of the governments of the sending and receiving states with civil society organizations. [1] Okano-Heijmans, Maaike and Price, Caspar, “Providing consular services to low-skilled migrant workers: partnerships that care”, Global Affairs, Vol. 5 No. 4-5, 2019, p. 436. [2] Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores, “13th labor rights week comes to a close in Mexico´s US consulates”, Press Bulletin, September 6, 2021 [3] Ibid. [4] Gómez Arnau, Remedios, México y la protección de sus nacionales en Estados Unidos, Centro de Investigaciones sobre Estados Unidos de América, 1990, p. 127. [5] Bada, Xóchitl, and Gleeson, Shannon. “A New Approach to Migrant Labor Rights Enforcement”, Labor Studies Journal Vol. 40 No. 1, 2015, pp. 42-44. [6] Bureau of International Labor Affairs, Joint Ministerial Declaration on Migrant Workers Signed by US Secretary of Labor, Mexican Secretary of Labor and Social Welfare, April 3, 2014. [7] SRE, Derechos Laborales de Personas Mexicanas en el Extranjero: Semana de Derechos Laborales en Estados Unidos, Datos Abiertos. [8] Okano-Heijmans, Maaike and Price, Caspar, “Providing consular services to low-skilled migrant workers: partnerships that care”, Global Affairs, Vol. 5 No. 4-5, 2019, p. 436. [9] See, for example Bada, Xóchitl, and Gleeson, Shannon. “A New Approach to Migrant Labor Rights Enforcement”, Labor Studies Journal, Vol. 40 No. 1, 2015, 32-53 [10] Græger, Nina, and Leira, Halvard, “Introduction: The Duty of Care in International Relations” in The Duty of Care in International Relations: Protecting citizens beyond the border, eds. Nina Græger, and Halvard Leira, 2019, p. 3. [11] Bada, Xóchitl, and Gleeson, Shannon, 2015, p. 45. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer, or company. Table 1. Summary of results of the Labor Rights Week 2009-2021

Note: Participant agencies and other consulates totals could participate in different editions but are counted separately. Sources: 2009-2020 SRE, Derechos Laborales de Personas Mexicanas en el Extranjero: Semana de Derechos Laborales en Estados Unidos, Datos Abiertos, and 2021 SRE, “13th labor rights week comes to a close in Mexico´s US consulates”, Press Bulletin, September 6, 2021.

This post was originally published February 4, 2021, by the CPD Blog at the USC Center on Public Diplomacy here uscpublicdiplomacy.org/blog/public-consular-diplomacy-its-best-case-mexican-consular-id-card-program. We look forward to sharing widely and hope you´ll do the same. The Mexican Consular ID card (MCID or Matrícula Consular) program is considered a successful public-consular diplomacy initiative. It resulted in significant benefits for the Mexican community living in the United States, creating long-lasting partnerships between Mexican consulates and local authorities, and financial institutions. With the focus on security in the U.S. after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, Mexico's government decided to increase the security features of the MCID, which has been produced by the consulates since 1871. Consular offices started issuing the new high-security consular IDs cards in March 2002 while there were changes in banking regulations due to the USA Patriot Act of 2001. Besides the new security features, the Matrícula included additional information useful for local authorities and banks, such as the bearer's U.S. address. These added characteristics allowed banks, police departments and sheriffs' offices across the United States to appreciate it as a valuable tool and begin to recognize it as a form of ID. Despite pressure from anti-immigrant groups, the Treasury Department reaffirmed banks' possibility of accepting foreign government-issued identification documents, including the MCID, in September 2003. Wells Fargo was the first bank to accepted it and opened 400,000 bank accounts using the Matrícula from November 2001 to May 2004. Other financial institutions quickly followed. Therefore, by 2010, 400 financial institutions did the same, and 17 consulates signed 45 agreements with banks and credit unions. The Mexican Consular ID card was also seen as a step toward the financial inclusion of Latinos and immigrants; hence, the Federal Deposits Insurance Corporation (FDIC) promoted the collaboration with Mexico's consular network across the United States through the New Alliance Task Force. The benefit for the Mexican community was dramatic and very concrete. Having a bank account opened the door of financial inclusion. The Matrícula acceptance jumped dramatically in a short time. Consequently, as of July 2004, the Mexican Consular ID card “was accepted as valid identification in 377 cities, 163 counties, and 33 states…as well as…1,180 police departments…and 12 states recognize the card as one of the acceptable proofs of identity to obtain a driver's license.” After a hard pushback against issuing driver's licenses to undocumented migrants, some states reconsidered their position. “As of July 2015, 12 states…issued cards that give driving privileges...[to them]. Seven of these came on board in 2013.” Some states recognize the Matrícula as a form of identification for obtaining a driver's license, even as the implementation of the REAL ID Act of 2005 is finally moving forward. The search for the acceptance of the consular ID cards pushed consulates, for the first time as a large-scale operation, to reach out to potential partners, including banks, credit unions, city mayors, country supervisors, chiefs of police and sheriffs' officers across the U.S. They also met with local institutions such as libraries and utility companies to promote the benefits of the Matrícula Consular. It was a massive public-consular diplomacy initiative undertaken by the Mexican consular network across the United States. The focus was on advocacy, explaining the advantages of recognizing the MCIC as a form of identification for their institutions. It resulted in establishing a direct dialogue with thousands of authorities and financial institution officers, which in many cases developed into strategic alliances or at least meaningful collaborations. The benefit for the Mexican community was dramatic and very concrete. Having a bank account opened the door of financial inclusion, which includes being eligible for certain credits and loans, facilitating and reducing the cost of wiring money home, increasing the possibility to save and invest, and bypassing the usage of money lenders and wiring services to cash paychecks and sending money. Besides, having a form of identification also allowed them to come forward as witnesses of crimes, identify themselves to the police, access medical care, have greater participation in PTA meetings, and in some states, access to driver's licenses. For Mexico´s consulates, the Matrícula Consular opened the door for the collaboration with the Federal Reserve in the Directo a Mexico program, reduced the costs of remittances, and promoted its investment in their home communities, mainly through the 3x1 matching fund's program. As an outcome of the MCIC program's tremendous success, other countries followed with their own consular ID card programs. The Matrícula program experienced significant updates in 2006 and 2014. Today it continues to be a valuable resource for the Mexican community living in the United States. In 2019, 811,951 consular ID cards were issued by consular offices north of the border, with a monthly average of 67,663. The Mexican Consular ID card program is an excellent example of public-consular diplomacy, where Mexican consulates work toward establishing partnerships with local, county and state authorities to benefit the Mexican community. The program also showcases Mexico's successful consular diplomacy and the value of engaging with local and state stakeholders in its overall foreign policy. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company. |

Rodrigo Márquez LartigueDiplomat interested in the development of Consular and Public Diplomacies. Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|