In the chapter “Consular Diplomacy in the face of U.S. demography and society in the 21st Century,” of the book La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempo de Trump, Ambassador Juan Carlos Mendoza Sánchez explains that demography changes in the United States have resulted in the expansion of nativist movements and anti-immigrant sentiments amongst the white population. He also details Trump´s changes to immigration policies and Mexico´s response to these challenges thru the implantation of an active and innovative Consular Diplomacy. In the section titled “A new demography face that scares the WASP sector,” the Ambassador pinpoints June 18, 2003, as a milestone because it was the day when the Latino community in the U.S. reached 38.8 million turning into the first minority, overpassing the Afro-American population.[i] As a result, alarms rang amongst the conservative white people, and their response to this “invasion” was the creation and expansion of nativist and anti-immigrant policies. Mendoza Sánchez details the history of anti-immigrant regulations in the U.S., starting from infamous California´s Proposition 187 of 1994 to Samuel Huntington´s book Who are we?[ii] Latino population's fast growth in the U.S. resulted in being the majority group in 30 cities, so the Ambassador states that “it is not unfounded the white-population fears of becoming a minority in their own country [and that fear] have slowly developed into anti-immigrant sentiments, and policies to make the U.S. unattractive to those who live there.”[iii] Donald Trump`s presidency is just a new and more radical chapter in the U.S. immigration policy. In the second part of the chapter, Ambassador Mendoza Sánchez explains that it was a radical change in the designation of undocumented migrants as threats to national security and public safety in two Executive Orders signed by the President. He also details some of the multiple changes to immigration policies, guidelines, and enforcement operations to criminalize undocumented immigration, with a particular focus on Mexico´s border and the Latino population.[iv] Another significant change was the end of enforcement priorities; thus, turning every single undocumented immigrant a target. Considering the existence of three million of mixed households meant the possibility of massive deportation that would have tremendous social consequences in the U.S. consequences of the new enforcement guidelines.[v] In the section “New challenges for Mexican Consular Diplomacy,” Mendoza Sánchez emphasizes that immigration policy changes have a direct impact on Mexicans in the U.S. It presents one of the biggest challenges to Mexico´s Consular Diplomacy. He identifies ten of them, but here I only include six:

The Ambassador highlights that there are more Mexican with immigration status than undocumented ones, for the first time in ages.[vii] This fact is unknown in the U.S. and contradicts the current anti-immigrant rhetoric that most Mexicans are undocumented. He explains that undocumented persons tend to live in sanctuary cities, and the implementation of policies to limit resources to those authorities will affect them.[viii] Fortunately, it has not been occurred yet, mostly thru lawsuits. Mendoza Sánchez writes that the Mexican community's geographical dispersion across the U.S. is one of the biggest challenges for consulates that cover large territories. The Mexican government's response was the establishment of the Mobile Consulate program that in the 21st century expanded into the Consulado sobre Ruedas (Consulate on Wheels) initiative.[ix] These activities were crucial for assisting vulnerable Mexicans after Trump´s inauguration.[x] Additionally, he identifies that “developing synergies with pro-immigrant organizations, authorities, other countries’ consulates, and minority groups is one of the most effective activities for consulates under the current circumstances.”[xi] Consular Diplomacy in action. In response to the enhanced anti-immigrant context, the government of Mexico designed a Consular Diplomacy strategy that contained three main activities:

He briefly explains the FAMEU program implemented in 2017 that had a 50 million dollar extraordinary budget. He briefly mentions Local Repatriation Arrangements[xiii] that help Border consulates in the orderly and humanly repatriation of Mexican nationals.[xiv] These arrangements are a clear example of Maaike Okano-Heijmans´ Consular Diplomacy definition because they are “diplomatic” in nature but are negotiated, signed, and implemented locally. Then the Ambassador explains five different programs part of Mexico`s Consular Diplomacy: a)Protection to Mexicans Abroad Innovations (Innovaciones en la proteccion a mexicanos).

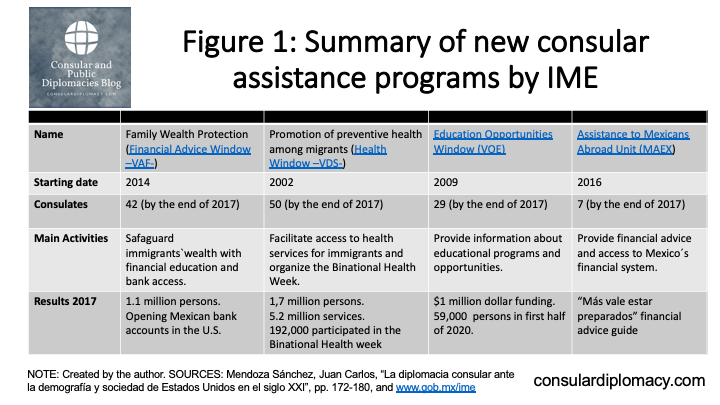

d)Education Opportunities Window (Ventanilla de Oportunidades Educativas). e)Promotion of preventive health among migrants (Promoción de la salud preventiva de los migrantes). Even though Mendoza Sánchez briefly describes each program, I do not include them here. In Figure 1, located at the end of the post, you can find a summary. All of them are innovative consular undertakings of Mexico`s Consular Diplomacy, which some countries are replicating. Most of them are unique and lay outside the traditional consular services offered by most ministries of foreign affairs to their citizens abroad. Four of the five programs highlighted by Ambassador Mendoza Sánchez are under the responsibilities of the Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior (Institute of Mexicans Abroad).[xv] I would like to share an extraordinary achievement of one of them: la Ventanilla de Salud or Health Window. In 2017, the American States Organization granted the “Inter-American Award on Innovation for Effective Public Management” to the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Health of Mexico for the Health Window program in the Social Inclusion category. That year the Health Windows at the consular network provided 5.2 million services to 1.7 million people.[xvi] Conclusion. The chapter is interesting to read as the Ambassador summarizes the origins of the Anglo-American population's growing resentment against immigrants and minorities. He explains that “for the WASP community, the country´s demographic change is a challenge to their way of life, values, and identity; therefore, the hardening of U.S. immigration policies.”[xvii] Mendoza Sánchez states that “to face this new reality, the Mexican Consular Diplomacy has engaged in the largest mobilization of its history with extraordinary programs… [with] the objectives of defending undocumented Mexican migrants´ rights and interests, and supporting them for better integration into their host communities.”[xviii] He also describes some of Consular Diplomacy´s most-forward-looking programs developed to take care of the Mexican community's needs during difficult times. The Ambassador recommends the following:

In this chapter, Ambassador Mendoza Sánchez implicitly highlights one of the essential features of Mexico´s Consular Diplomacy: its adaptability and scalability. As seen in Figure 1, most of the programs described in the chapter started in one or two consulates. After having good results, they were slowly expanded into a country-wide operation at all 50 consulates, and sometimes in other countries with large Mexican populations. [i] Mendoza Sánchez, Juan Carlos, “La diplomacia consular ante la demografía y la sociedad de Estados Unidos en el siglo XXI” in La Diplomacia Consular Mexicana en tiempos de Trump, Rafael Fernández de Castro (coord.), Mexico, 2018, p. 154. [ii] Ibid. p. 154-155. [iii] Ibid. p. 157-158. [iv] Ibid. p. 159. [v] Ibid. p. 161. [vi] Ibid. 163. [vii] Ibid. p. 164. [viii] Ibid. p. 165. [ix] Ibid. p. 165-166 [x] Ibid. p. 165 [xi] Ibid. p. 167. [xii] Ibid. p. 168. [xiii] The LRAs are signed by the Consulates of Mexico and DHS agencies. Border LRAs also include the participation of the National Migration Institute of Mexico. Find a public version of the 9 border LRAs here. [xiv] Ibid. p. 169-170. [xv] To learn more about Mexico`s government engagement with its diaspora, read the multiple publications of Alexandra Delano included in Google Scholar. See also Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior # 107 Comunidades Mexicanas en el Exterior, May-August 2016; de Cossío Díaz, Roger, et al., Mexicanos en el Exterior: Trayectoria y perspectivas 1990-2010, Instituto Matías Romero, 2010; Laglagaron, Laura, Protection through Integration: The Mexican Government Efforts to Aid Migrants in the United States, Migration Policy Institute, January 2010; and Rannveig Mendoza, Dovelyn and Kathleen Newland, Developing a Road Map for Engaging Diasporas in Development: A Handbook for Policymakers and Practitioners in Home and Host Countries, International Organization for Migration and Migration Policy Institute, 2012. [xvi] Ibid. p. 179. [xvii] Ibid. p. 180. [xviii] Ibid. p. 180. [xix] Ibid. p. 181. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Rodrigo Márquez LartigueDiplomat interested in the development of Consular and Public Diplomacies. Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|