Following up on my previous post, “Recent studies on consular diplomacy: reevaluating the consular institution,” about recent works on consular diplomacy, I want to share two great articles I just finished reading. But first, I want to share that the Journal of Public Diplomacy recently published my practitioner's essay titled Beyond Traditional Boundaries: The Origins and Features of the Public-Consular Diplomacy of Mexico. It is open access, so I invite you to read it too. The first article I just read is titled “Duty of Care: Consular Diplomacy Response on Baltic and Nordic Countries to COVID-19”, and was published by the Hague Journal of Diplomacy (open source article).[i] The second is “Going East: Switzerland´s east consular diplomacy toward East and Southeast Asia”, written by Pascal Lottaz and focuses on opening Swiss consular offices in the Far East in the 1860s. So, let´s start with the comparative study of the Baltic and Nordic countries´ consular diplomacy in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. “Duty of Care: Consular Diplomacy Response on Baltic and Nordic Countries to COVID-19” The article is a must-read for anybody interested in the latest developments in diplomatic practices. It includes discussions on the evolution from consular services into consular diplomacy through the expansion into foreign policy, digital diplomacy, and citizen-centric initiatives.[ii] There are few comparative studies of consular diplomacy; therefore, this essay is very much welcomed. It also showcases the different responses to the biggest-ever challenge for consular assistance, as the pandemic was once in a millennia occurrence that closed down the entire world. Birka, Klavinš, and Kits explain the concept of “Duty of Care” and the importance of the state–society relationship in implementing consular assistance to citizens abroad in the real world. They classify this responsibility into two categories the “pastoral care concept [in] which citizens are objects to be protected [and the] neoliberal governmentality conception where citizens are expected to take on more responsibility for their own well-being.”[iii] The authors define the concept “as the assistance and protection of citizens through guidance and information provision, enabling citizens to make informed decisions and care for themselves. However, when faced with the pandemic, all states made minor adjustments to this approach and assumed some level of a pastoral DoC role by exceeding normal consular services provision.”[iv] Birka, Klavinš, and Kits also discuss the changes in consular affairs, particularly the refocusing of ministries of foreign affairs into a greater engagement with its citizens and the inclusion of new diplomatic tools such as digital and diaspora diplomacies into their primary functions. The rise of consular diplomacy is part of these transformations and was put to a big test with the COVID-19 pandemic. The evaluation and comparison of the response of the Nordic and Baltic countries to the pandemic is a significant contribution to the field of consular diplomacy studies. Despite their similarities, the eight countries have essential differences in their consular emergency responses. The categorization of the countries' consular responses to the pandemic, reflected in tables 2 ”extent of pastoral care provided”[v] and 3 “aspects of consular diplomacy,”[vi] could be applied in other comparative or single-country case studies. A key highlight of “Duty of Care: Consular Diplomacy Response on Baltic and Nordic Countries to COVID-19”, is the importance of having robust relationships among different MFAs to be able to evolve from consular coordination schemes to full-fledged consular diplomacy, which happened among the Nordic states but not in the Baltic region. Regarding innovative approaches, Lithuania and Denmark stand out. By using their established connections with their diasporas, the two countries were able to mobilize them to assist their nationals in the first months of the pandemic.[viii] Citizens' active participation in helping governments distribute valuable information and their assistance to some people showcases the new role of citizens in diplomacy and consular assistance. The study underscores the significant contributions of information and communications technologies to diplomacy. Having a smartphone application with hundreds of thousands of users and being able to send SMS messages to all citizens abroad underline their vital role in today´s consular diplomacy. Even traditional MFAs webpages were crucial in disseminating information to people stuck overseas and their family members in the home country. Birka, Klavinš, and Kits successfully explain the critical elements of today´s consular diplomacy, and I am sure their comparative study will be highly cited work in the field. It is a must-read for everybody interested in today´s diplomacy, not only consular affairs. Now, let´s move on to the historical essay on Switzerland's consular diplomacy in the late 19th century. “Going East: Switzerland´s east consular diplomacy toward East and Southeast Asia” From the onset, it is hard to imagine why a small land-locked country like Switzerland would be interested in opening consulates in Asia. However, after reading the article, it all makes sense; therefore, this essay is also a valuable contribution to the field of consular diplomacy. It is fascinating to learn about how trade interests pushed the opening of Swiss consulates in Manila (1862), Batavia (now Jakarta) in 1863, and Yokohama and Nagasaki (Japan) a year later. Back then, the Alps´ nation had only three embassies -Paris, Vienna, and Turin (its three big neighbors)- but had 77 honorary consulates; therefore, most of its foreign activities were conducted by non-official consular officers rather than state diplomats.[ix] “Going East: Switzerland´s east consular diplomacy toward East and Southeast Asia” showcases the linkage between colonial powers and small European countries in their trade expansion two centuries ago. Switzerland was able to open two new consulates with the assistance of Spain and the Netherlands. Besides, the U.S. and the Dutch helped Swiss diplomats sign a friendship treaty with Japan in 1864 after a failed attempt.[x] Lottaz identifies the need for new markets for Swiss manufactured goods as the main objective in expanding relations with the Far East, which was driven mainly by a few tycoons, also called “Federal Barons.”[xi] He also ascertains that the expansion resulted from “the opportunity structure of the colonial era.”[xii] Another issue that surfaced in this research was the concern about giving an advantage to a company with the designation of honorary consul abroad, issue that later was overturned, as the Swiss government designated the same person the second time around.[xiii] This subject still matters today, as demonstrated by the recent investigation into honorary consuls´ criminal activities and nefarious behaviors (See below). Here are some topics that came up in the conclusions of the article which could be further studied:

The article reinforces the idea that most of the consular activities in the 19th century were focused on protecting trade interests, which were part of the national interest, rather than individual citizens. This perspective differs in the case of Mexico, which early on focused on protecting citizens in distress in the U.S. that had no trade connections. “Going East: Switzerland´s east consular diplomacy toward East and Southeast Asia” is a worthwhile contribution to understanding the links between trade and diplomacy and the merging of consular and diplomatic functions into what is known today as consular diplomacy. A brief comment on Consuls and Captives: Dutch-North African Diplomacy in the Early Modern Mediterranean Before finishing, I just want to briefly comment on the book Consuls and Captives: Dutch-North African Diplomacy in the Early Modern Mediterranean by Erica Heinsen-Roach. It is not new, but it is fascinating historical research that demonstrates that diplomacy is not a uniquely European creation. The fact is that for nearly 300 hundred years, Maghribi corsairs and rulers in Morocco, Algiers, and Tunis, were able to deal on their own terms with European powers, mainly under the title of consuls, who performed diplomatic duties. The book has a human dimension as it centers on the adventurous lives of Dutch consuls and a couple of non-resident ambassadors stationed on the African shores of the Mediterranean Sea. It provides an excellent example of the role of consuls in diplomacy. One of the defining elements of consular diplomacy is high-visibility consular cases[xiv]; therefore, what is more relevant than the enslavement of Dutch nationals in the Mediterranean and the government’s efforts to release them? As seen in the Swiss expansion to Asia, in this case, consular protection of citizens in distress was mainly related to trade interests, as the corsairs’ seizure of Dutch vessels and citizens in the Mediterranean affected the national interests. However, it seems that there is also a humanitarian responsibility, described as “duty of care” by the Dutch authorities, to look after its nationals abroad, particularly in these situations where the government's action made the difference between freedom and slavery. A final note on the honorary consuls’ global investigation. Recently, ProPublica and the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists launched a global investigation on honorary consuls titled “Shadow diplomats: The Global Threat of Rogue Diplomacy.” This study is unique as consular affairs are typically covered by the media on crises or high-visibility consular cases, not the consular officials´ performance and activities. Sadly, it focuses on the “rogue” side rather than honorary consuls´ substantial contributions, especially in assisting distressed citizens abroad and promoting greater ties between nations. Most of the cases described in the research would still exist, as honorary consular usually are citizens of the host country rather than foreigners. The only, and important difference is their status as consular officers granted by both the receiving and the sending governments´. Of course, any criminal activity should be prosecuted, and abuses should be reported and sanctioned. [i] Birka, I., Klavinš D., & Kits, R. (2022). Duty of Care: Consular Diplomacy Response of Baltic and Nordic Countries to COVID-19. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy, 17(2022), 1-32. [ii] Birka, I., Klavinš D., & Kits, R. (2022). [iii] Tsinovoi A. and Adler-Nissen, R. (2018) Inversion of the “Duty of Care”: Diplomacy and the protection of Citizens Abroad, from Pastoral Care to neoliberal Governmentality. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy (13) 2, cited in Birka, I., Klavinš D., & Kits, R. (2022). p. 7. [iv] Birka, I., Klavinš D., & Kits, R. (2022). p. 26. [v] Birka, I., Klavinš D., & Kits, R. (2022). p. 16. [vi] Birka, I., Klavinš D., & Kits, R. (2022). pp. 23-24. [vii] Birka, I., Klavinš D., & Kits, R. (2022). pp. 22-24. [viii] Birka, I., Klavinš D., & Kits, R. (2022). pp. 22-24. [ix] Lottaz, P. (2020). Going East: Switzerland´s east consular diplomacy toward East and Southeast Asia. Traverse: Zeitschrift für Geschichte = Revue d´historie 27(1), p. 23-24. [x] Lottaz, P. (2020). p. 28. [xi] Lottaz, P. (2020). pp. 25-26. [xii] Lottaz, P. (2020). p. 24. [xiii] Lottaz, P. (2020). pp. 24 and 30. [xiv] See Maaike Okano-Heijmans. (2011). Changes in Consular Assistance and the Emergence of Consular Diplomacy. In Jan Melissen and Ana Mar Fernandez (eds.) Consular Affairs and Diplomacy, pp. 21-41. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed here are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer, or company.

0 Comments

In November 2022, I had the fantastic opportunity to attend the Summit on Digital Diplomacy and Governance organized as part of the 20th anniversary of the DiploFoundation. The main takeout of the superb conference is that, as in the past, technology is changing diplomacy very fast. Diplomats and ministries of foreign affairs (MFAs) need not just to try to keep up with the changes but be prepared to take advantage of the opportunities it brings and protect against the threats it presents. As it was a decade ago with the appearance of social media, nowadays, diplomats and people who perform diplomatic functions must be aware of the rapid changes happening in the digital realm. From the rise and consolidation of TechPlomacy (Technology Diplomacy) and Digital Foreign Policy to the upcoming arrival of quantum computers and the fast-changing face of Artificial Intelligence, technology is changing diplomacy and the world´s geopolitics. The adaptation of diplomacy to technological revolutions is not new. To learn more about the topic, make sure you visit Diplo´s interactive page on the History of Diplomacy and Technology or watch the very educational and informative Masterclass Diplomacy and Technology: a Historical journey, which at the end of each chapter has a great surprise. Diplo´s uniqueness There are few places or institutions in today´s world that bring together specialists in ICT and internet governance and practitioners of diplomacy in such a dynamic way like Diplo does. It has achieved this perfect communion through consistency, innovation, and total commitment to capacity building with a particular focus on small and developing states. Another marvelous aspect of Diplo is that the Summit and all events it organizes have an incredible array of participants from all corners of the world, with a considerable proportion of women and the Global South. Furthermore, many of the attendees were Diplo´s Alumni, so the camaraderie of the Summit was just unbelievable. I even learned how to dance Jerusalema! Summit on Digital Diplomacy and Governance. The Future of Diplomacy: From Geopolitics to Emerging Technologies. According to Diplo, the Summit had 33 sessions, 68 speakers, and 510 participants (DiploFoundation, 2022). Here is a video about it. For a summary of the event, read the Digwatch Newsletter, Issue 75 (December 2022). One of the highlights was the idea that digital diplomats “need to acquire new skills in digital governance: An understanding of the new geopolitics and geo-economic landscape, knowledge of the technology fuelling these developments, and the skills to engage with other actors, including tech companies, academia, and civil society” (Geneva Internet Platform, 2022, p. 6). For a complete summary of the meeting, visit Highlights from the Summit on Digital Diplomacy and Governance To learn more about the participants' perspectives, Diplo created a series of videos and messages titled “Summit in a minute”, which I recommend watching/reading. You will see the significant diversity of the Summit´s attendees and their broad perspectives. Opportunities for learning about new technology and its impact on diplomacy. The future is happening now, as Tech giants and digital nomads are working hard to code new technologies and apps that will transform the world. In the last decade, we have seen the disruptive power of social media. The coming changes will likely have a more significant impact, from automation affecting millions of jobs and livelihoods to data mining and artificial intelligence. Therefore, I encourage diplomats to ride the wave of technological changes before it is too late. Fortunately, DiploFoundation has many tools and options for learning and engaging. Here are some courses offered by Diplo:

You can also read my blog posts about the subject here:

REFERENCES: DiploFoundation. (2022). Highlights from the Summit on Digital Diplomacy and Governance. Geneva Internet Platform (2022) Digwatch Newsletter, Issue 75 (December 2022). DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company.  This blog post is dedicated to all the Mexican diplomats and U.S. legal teams that work with death penalty cases involving Mexicans, especially in memoriam of Imanol de la Flor Patiño, an exemplary person. Today, twenty years ago, Mexico sued the United States in the International Court of Justice for violations of the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations (VCCR), specifically Article 36, which provides the right of consular notification to foreign citizens detained abroad. The case concerning Avena and other Mexican nationals against the United States was a milestone in Mexico's assistance to its citizen overseas, particularly in the United States. In March 2004, the Court rendered its judgment against the United States, thus becoming an instrumental decision for the consular protection of the rights of Mexicans arrested north of the border and also for the 52 named cases (Gómez Robledo 2005, p. 183). The Avena case is Mexico's most consequential consular protection case because it overhauled the assistance consulates provide to distressed citizens and raised the relevance of consular affairs inside the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Background In 1976, the United States Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty. In 1993, a Mexican was executed in Texas; he was the first Mexican put to death after the reimposition of capital punishment. His execution was a big issue in Mexico which generated "more than a hundred condemnatory articles in the [Mexican] press, and pronouncements by not only the minister of Foreign Affairs but the President [of Mexico]" (González de Cossío, 1995, p. 102). As a result, Mexico took a series of actions that helped prepare for the presentation of the Avena case in 2003. One immediate step was to interview all Mexicans on death row. As part of the process, consular officials identified a systemic violation of the right to consular notification in capital cases (González Félix, 2009, p. 218-220). In addition, in 1997, Mexico asked the Inter-American Court of Human Rights for an Advisory Opinion (OC-16/99) about the consular notification. It was a multilateral effort and was not bidding; thus, it was not a direct confrontation with the U.S. The Court published its opinion in 1999, stating that foreign individuals have certain rights under the VCCR, such as the rights of information, consular notification, and communications. Besides, it determined that the sending state and its consular officers also have the right to communicate with its detained nationals (Cárdenas Aravena, n.d). In 2000, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Mexico launched a new program to assist Mexicans on death row in the United States. This program complemented the legal training that some Mexican diplomats received as part of the official collaboration with the University of Houston that started in 1989 (see, for example, De la Flor Patiño, 2017 and number 109 of the Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior). Enhancing consular protection With the arrival of President Fox in 2000, Mexico's government stepped up its engagement with the Mexican community in the United States intending to enhance consular protection. Mexico started negotiating a bilateral migration agreement with the recently inaugurated U.S. president, George W. Bush. The government established the Presidential Office for Migrants Abroad, promoted the Mexican Consular ID Card, and created and expanded consular programs such as the Binational Health Week and the Ventanilla de Salud (Health Desk). In early 2002, the country ratified the Optional Protocol concerning the Compulsory Settlement of Disputes of the VCCR, to which the United States was also a party (González Félix, 2009, p. 221-222), thus offering a binding conflict resolution mechanisms. Meanwhile, the number of Mexicans sentenced to death and executed by U.S. authorities increased, creating an uproar in Mexico. In January 1995, there were 23 Mexicans sentenced to death in the U.S. (González de Cossío, 1995, p. 108). The ICJ's Avena Judgment decision of 2004 included 51 cases. From 1997 to 2002, four nationals were put to death in Texas and Virginia (Death Penalty Information Center, n/d). Even President Fox suspended a trip to president's Bush ranch in Texas in August 2002 as a protest of the execution of a Mexican in the same state (Gómez Robledo 2005, p. 178-179). Meanwhile, Paraguay in 1998 and Germany in 1999 requested the intervention of the ICJ regarding the Breard and LaGrand cases related to violations of consular notification rights by U.S. authorities. In Paraguay's case, the proceedings were stopped after the execution of its national in 1998, while the German brother's case continued even after both were put to death in 1999. Both instances were significant for Mexico's consular protection of its nationals on death row. According to Gómez Robledo (2005), after LaGrand's ICJ decision in June 2001, Mexico tried to work with the United States regarding the Mexicans sentenced to death whose rights were violated by local authorities by denying the consular access with no avail (p. 178-179). The Avena Judgment and its repercussions In January of 2003, in a bold action, Mexico presented in the ICJ the Avena case against the United States for violations of Article 36 of the VCCR regarding the death penalty cases of 54 Mexicans in the United States (Covarrubias Velasco, 2010, p. 133-134). The case had significant implications and had very high visibility in Mexico, particularly at a time when the migration to the United States grew very fast, passing from 4.3 million in 1990 to 9.1 million in 2000 (Rosenbloom & Batalova, 2022). After more than a year, which included one provisional measure, on March 31, 2004, the ICJ issued its judgment. In summary, "the ICJ concluded that the United States had violated its obligations under the Vienna Convention [on Consular Relations] by failing to properly notify Mexican nationals of their rights to have Mexican consular officials notified of their arrest, which in turn deprived Mexican consular officers of their right under Article 36 to render assistant to their detained nationals "(Garcia, 2004, p. 14). More significantly, "the Court ordered the United States to provide judicial review to each and every one of the fifty-one Mexicans named in the suit whose Article 36 rights had been violated, and to determine whether the failure to timely advise the consulate of their arrests resulted in "actual prejudice to the defendant." Importantly, the United States judiciary also had to review and reconsider the convictions and sentences as if the procedural default did not exist" (Kuykendall and Knight, 2018, p. 808-809). It was a massive victory for the rights of the Mexicans on death row, as it was mandatory for the U.S. government. The Judgment bound the U.S. to the 51 Mexicans with capital sentences, regardless of the eventual outcome of each case. The Avena case was a milestone for Mexico's consular protection because:

However, not all has been good news. Regarding the demand by the ICJ court that the U.S. review and reconsider the cases of the 51 Mexicans named in the Avena Judgment, the federal government has faced internal challenges. The most important of these was the Supreme Court's decision regarding the case of Medellin vs. Texas (p. 491). In 2008, the Court indicated that the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations is not a self-execution treaty, therefore, the U.S. Congress must legislate so it could become part of the U.S. law (Medellin vs. Texas (p. 491-492). Regardless of U.S. authorities' continuous breach of their international obligations, there have been crucial domestic adjustments. In some cases, State courts decided to review the death penalty cases based on the Avena Judgment and provided relief to Mexicans on death row. In addition, some states "have at least some statutory requirements concerning consular notification…[and] beginning in December 2014, the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedures now provide that at an initial appearance, the judge must inform the defendant" (Kuykendall and Knight, 2018, p. 824) that if they are foreigners, they have the right to contact their consulates. Besides, since the start of the Avena case in 2003, the support for the death penalty in the U.S. has been declining ever so slowly. In conclusion, the Avena case was Mexico's most consequential consular protection case, which enormously influenced the emergence of the country's public-consular diplomacy. References Cárdenas Aravena, C. (n.d). La Opinión Consultiva 16/99 de la Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos y la Convención de Viena de Relaciones Consulares. Covarrubias Velasco, A. (2010). Cambio de siglo: la política exterior de la apertura económica y política. México y el mundo: Historia de sus relaciones exteriores. Tomo IX. El Colegio de México. Death Penalty Information Center, n.d. Execution of Foreign Nationals [in the United States. De la Flor Patiño, I. (2017). Pena de muerte en el condado de Harris, una mirada a través del cristal de la Universidad de Houston. Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior (109), 99-123. Gallardo Negrete, F. (2022, April 27). La pena de muerte en México, una historia constitucional. Este País. Garcia, M. J. (2004, May 17). Vienna Convention on Consular Relations: Overview of U.S. Implementation and International Court of Justice (ICJ) Interpretation of Consular Notification Requirements. Congressional Research Service. Gómez Robledo V., J. M. (2005). El caso Avena y otros nacionales mexicanos (México c. Estados Unidos de América) ante la Corte Internacional de Justicia. Anuario Mexicano de Derecho Internacional Vol. V, 173-220. https://revistas.juridicas.unam.mx/index.php/derecho-internacional/article/view/119/177 González Félix, M. A. (2009). Entrevistas: Pasajes Decisivos de la Diplomacia. El Caso Avena. Interview by C. M. Toro. Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior (86), 215-223. June. González de Cossío, F. (1995). Los mexicanos condenados a la pena de muerte en Estados Unidos: la labor de los consulados de México. Revista Mexicana de Política Exterior (46) 102-125. Spring. Kuykendall, G. & Knight, A. (2018). The Impact of Article 36 Violations on Mexicans in Capital Cases. Saint Louis University Law Journal 62(4), 805-824. Rosenbloom, R. & Batalova, J. (2022, Oct. 13). Mexican Immigrants in the United States. Migration Policy Institute. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company. I am extremely happy to share with you the article Beyond Traditional Boundaries: The Origins and Features of the Public-Consular Diplomacy of Mexico, published in the newest edition of the Journal of Public Diplomacy. You can read it or download it in this link: https://www.journalofpd.com/_files/ugd/75feb6_82201616bab74db6b1f877c8deb734d6.pdf Besides, if you are interested in the origins of Mexico's consular diplomacy, you can read my previous post here. You can also read additional posts about consular diplomacy, such as:

DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company. Maribel (not her real name) went with her family to a Mexican consulate in the U.S. She was there to get a health referral to have a free mammogram at the local health clinic. Besides, her youngest kid, Jaime, needed eyeglasses, so she got a voucher for free prescription glasses from a well-known grocery store. On the same visit, Eduardo, a Guatemalan citizen and Maribel's partner received screenings for blood glucose and blood pressure. All these services were provided by the Ventanilla de Salud program (VDS -Health Desk/Window-)[i], a public-consular diplomacy effort that will celebrate its 20th anniversary next year. Since its creation as a pilot program in Southern California in 2003, the VDS at the Mexican consulates (and mobile units) has provided more than 45.8 million health-related services to 18.3 million people. Its services are not exclusively for Mexicans, so many more people, including U.S. citizens, have benefited from this effort. The VDS does not solve all the health-related barriers and issues faced by the Mexican migrants in the U.S.; however, it certainly alleviates some of their anguish and distress. Background. The primary motivation behind establishing the VDS is the unequal access to health services in the U.S. by Hispanics in general and undocumented migrants in particular, even after the enactment of the Affordable Care Act of 2010. In 2016, 24 million persons did not have health insurance, and the percentage of Hispanics uninsured of the total grew from 29% in 2013 to 40%. In 2019, two out of five Mexican migrants did not have insurance (38%), “compared to 20% of all immigrants and 8% of the U.S. born.”[ii] Two years later, the percentage of uninsured Mexican migrants diminished by 1% to reach 37% in 2021.[iii] In the United States, an uninsured person typically pays full price for medical expenses, while an insured individual will receive negotiated discounts from their insurance, so the cost drops dramatically. The passing of Proposition 187 in California in 1994 significantly impacted the Hispanic community, not only the undocumented Mexican population, although it never came into force.[iv] Most migrants stayed away from medical services due to the fear of being taken away by immigration authorities and the confusion regarding immigration’s public charge, particularly during the Trump Administration.[v] Besides, the creation of the Binational Health Week in 2001 by the government of Mexico and the Health Initiative of the Americas (HIA) gave a big push for establishing a permanent health office at the Mexican consulates that could also provide information year-round (Link to the blog post about the Binational Health Week). However, it was not that easy, as the VDS required having non-official personnel inside the consulate. Raúl Necochea López details the difficulties that had to be overcome to open the Health Desks in the consulates´ offices, as it was “a significant departure from the established restrictive norms about the use of consular resources,”[vi] The biggest issue was the permanent presence of non-consulate personnel at the consular premises. After some time, finally, in February 2002, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Mexico accepted the idea, and a pilot program proposal was developed. In 2003, the Consulates of Mexico in San Diego and Los Angeles opened the first VDS as a pilot project. After their initial success, the Ministry of Health of Mexico has provided funds for the program since 2006. Taking advantage of the hundreds of persons that visit the consulates every day was a determining factor for the health institutions in establishing a permanent health office at the consular premises. It provided access to hard-to-reach populations in a secure and culturally appropriate environment. “A key factor in the [partner organizations’] ability to reach this population is the fact that the consulate is generally considered a trustworthy space in the sense that a person´s migration status will not be at risk.”[vii] What is the Health Window? The VDS is a designed space inside the consulate, generally in the public waiting area, attended by personnel of the local partner. The Health Desk provides health-related information and personalized counseling, makes referrals to a health clinic and other specialized services, and offers the opportunity to receive different types of screening. “The VDS program is a multistrategy approach to providing personalized assistance and outreach to Mexican immigrants unfamiliar with the U.S. health system.”[viii] The Health Desk program is a public-private partnership with the participation of Mexico´s Ministry of Health (providing funding and overseeing the program), the Institute of Mexicans Abroad (IME) through the consular network, and local government and non-government health care organizations, such as community health centers, hospitals, universities, migrant-serving institutions, and pharmacies. The local partners provide human and financial resources and knowledge, while the consulates offer a space for their activities. “The aim of this initiative is to build a network of informational windows [Health Desks] to increase knowledge about health and access to services for Mexican migrants and their families residing in the United States.”[ix] The VDS provides the following general services, which vary depending on several issues, most notably the available local resource and existing partnerships:

As the program evolved, more organizations began offering health-related services, from a wide variety of screenings and immunizations to access to quitting smoking programs and referrals to community health clinics. In 2015, the VDS served 1,525,504 persons who received 415,509 screening and 63,084 vaccinations.[xi] The VDS provided a wide variety of information, including health insurance, domestic violence, hypertension, diabetes, substance abuse, obesity, birth control, and mental and women´s health, among other topics.[xii] The evolution of the Heath Desk. After its initial success, the VDS expanded rapidly like other successful consular programs. Eleven consulates established Health Windows between 2004 and 2007. And, from 2008 to 2011, an “additional 38 VDS opened for a total of 50 affiliated with the Mexican consulates that work closely and in partnership with local health-care organizations.”[xiii] Two circumstances helped in the fast expansion of the program. The first one was the creation of a health commission of the Institute of Mexicans Abroad´s Advisory Council -CCIME- in 2003. The advisory council was the first of its type in the government of Mexico.[xiv] The second situation was the increase in the reunification of women and children in the U.S.,[xv] significantly changing the demographics and needs of the Mexican migrant community. Health care has become increasingly critical for new migrant families. For example, in 2013, women were 63% of the people served by the VDS.[xvi] An additional advantage of the Health Desk was that the IME organized several Jornadas Informativas (specific topic conferences) centered on health issues. It later created a special meeting of all VDS partner organizations, which was unique to the program. In December 2020, the 17th Annual meeting of the Health Desk program took place online due to the pandemic. In 2012, a Health Advisory Board was established with nine members to define the priorities of the VDS and make recommendations to promote the program´s sustainability. The board was one of the first to be established to strengthen the programs implemented by the IME. During the Covid-19 pandemic, the VDS played a crucial role in providing information to the community via social media and other forms of communication. In 2021, Mexico´s consular network in the United States helped provide 80,000 COVID-19 vaccines[xvii] not only to the Mexican community but also to Hispanics and from other countries. Through the years, the VDS has continued to evolve. For example:

The results of the Heath Desk. From 2003 until August 2022, the VDS served 18.3 million persons and offered 45.8 million health-related services, as described in Table 1, with the collaboration of around 600 local partners. Table 1. Ventanilla de Salud Program: persons serviced, and health-related services provided from 2003 to 2022 Period Persons Services 2003-2017 10 million* 18.4 million** September 2017-August 2018 1.5 million 5.8 million January-July 2019 700,000 1.8 million September 2019-August 2020 2.0 million 6.0 million September 2020-August 2021 3.0 million 8.5 million September 2020-August 2022 1.1 million 5.3 million TOTAL 18.3 million 45.8 million Note: A single person can receive multiple services. According to the Institute of Mexican Abroad, between 2003 and 2019, the VDS served 22 million persons who received 8 million health-related services. Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior (2021). Ventanillas de Salud (VDS). 21 November. Sources: *2003-2017. Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior, 2017. Las Ventanillas de Salud reciben el premio de la OEA a la Innovación para la Gestión Pública. Boletín Especial Lazos. 11 October. **The number of services only includes from 2012 to 2016. Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior, 2018. Resultados Programa VDS. 26 November 2016; updated March 2018. 09/2017-08/2018: Sexto Informe de Labores, SRE. 2018, p. 190; 01-07/2019; Primer Informe de Labores, SRE. 2019, p. 136; 09/2019-08/2020: Segundo Informe de Labores, SRE. 2020, p. 157; 09/2020-8/2021: Tercer Informe de Labores, SRE. 2021, p. 145; 09/2021-08/2022: Cuarto Informe de Labores, SRE. 2022, p. 142. The impact of the VDS is more significant considering that health issues affect the family on both sides of the border, as illnesses and other health problems can result in a reduction of income and an increase in expenses. Besides reaching out to millions of Mexicans in the U.S. through the VDS program, the consulates of Mexico have established long-term alliances with a wide range of health-related organizations, such as the American Cancer Society, the National Institute for Health, Georgia Lighthouse Foundation, and Emery University´s Rollins School of Public Health.[xviii] The program has also strengthened its collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Alliance for Hispanic Health.[xix] Recognizing the great benefits that the VDS provided, in 2017, the Organization of American States granted the “Inter-American Award on Innovation for Effective Public Management” in the Social Inclusion Innovation category.[xx] The opening of the VDS was a defining moment in Mexico´s public-consular diplomacy, as it allowed, for the first time, the permanent presence of community health organizations personnel inside the consular premises. Shortly after, other groupings, such as the banking and financial sectors, assigned people to the local consulate. Various consulates also opened new specific-purpose windows focused on educational opportunities and financial education. More recently, some three consulates have created new desks to provide specialized care to indigenous migrants. Conclusions. The Ventanilla de Salud or Health Desk program is another example of an innovative public-consular diplomacy of Mexico, working as a bridge between the Mexican community living in the U.S. and its network of health partners. Health referrals and screenings are not typical consular assistance programs. However, the VDS was a groundbreaking way for the government of Mexico, together with local partners, to care for the needs of the Mexican community in a country without universal health care. The VDS also initiated the consulates' transformation into community centers. The VDS helps the Mexican community in the U.S. to alleviate their barriers to accessing healthcare and solving health-related issues. A visit to a Health Window in a Mexican consulate can be a life-changing event or at least an opportunity to learn how to navigate the U.S. health system. [i] Other translations of the VDS program are Health Stations or Health Windows. Here it Desk and Window will be used. [ii] Israel, E. and Batalova, J. 2020. Mexican Migrants in the United States. Migration Policy Institute. 5 November. [iii] Rosenbloom, R. and Batalova, J. 2022. Mexican Immigrants in the United States. Migration Policy Institute 13 October. [iv] Márquez Lartigue, R. 2022. Public-consular Diplomacy that heals: The Binational Health Week Program. Blog about Consular and Public Diplomacies. 5 March. [v] Marina Valle, V., Gandoy Vázquez, W. L., and Valenzuela Moreno, K. A. 2020. Ventanillas de Salud: Defeating challenges in healthcare access for Mexican immigrants in the United States. Estudios Fronterizos, 21. July. [vi] Necochea López, R. 2018. Mexico´s health diplomacy and the Ventanilla de Salud program. Latino Studies (16), p. 483. [vii] Délano Alonso, A. 2018. From Here and There: Diaspora Policies, Integration and Social Rights beyond Borders, p. 78. [viii] González Gutiérrez, C. 2009. The Institute of Mexicans Abroad, An Effort to Empower the Diaspora. In D. R. Agunias (Ed.) Closing the Distance. How Governments Strengthen ties with their Diaspora, p. 94. [ix] Dávila Chávez, H. 2014. Comprehensive Health Care Strategy for Migrants. Voices of Mexico. Num. 98, Winter, p. 96. [x] Secretaría de Salud and Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. 2019. Strategy: Ventanillas de Salud, p. 7. [xi] Rangel Gómez, M. G., et. al. 2016. Ventanillas de Salud: A Program Designed to Improve the Health of Mexican Immigrants Living in the United States. Migración y Salud, p. 100. [xii] Rangel Gómez, M. G., et al. 2017. Ventanillas de Salud: A Collaborative and Binational Health Access and Preventive Care Program. Frontier in Public Health. 30 June. [xiii] Rangel Gómez, M. G., et al. 2017. Ventanillas de Salud: A Collaborative and Binational Health Access and Preventive Care Program. Frontier in Public Health. p. 3. 30 June.[xiv] Délano, A. 2009. From Limited to Active Engagement: Mexico’s Emigration Policies from a Foreign Policy Perspective. International Migration Review, 43(4), p. 791. [xv] Durand, J., Massey, D. S. & Parrado, E. A. 1999. The New Era of Mexican Migration to the United States. The Journal of American History, 86(2), p. 525-527. [xvi] Rangel Gómez, M. G., et al. 2017. Ventanillas de Salud: A Collaborative and Binational Health Access and Preventive Care Program. Frontier in Public Health, p. 2. 30 June. [xvii] Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. 2021. Tercer Informe de Labores, SRE, p. 146. [xviii] Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior 2018. Alianzas Estratégicas. Published 24 November 2016; updated March 2018. [xix] Dávila Chávez, H. 2014. Comprehensive Health Care Strategy for Migrants. Voices of Mexico. Num. 98, Winter, p. 98. [xx] Organización de Estados Americanos. 2017. V Premio Interamericano a la Innovación para la Gestión Pública Efectiva 2017. Acta Final de Evaluaciones. Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior. 2017. Las Ventanillas de Salud reciben el premio de la OEA a la Innovación para la Gestión Pública. Boletín Especial Lazos. 11 October. Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior. 2017. La OEA hace entrega de Premio Interamericano a las Ventanillas de Salud. Press Bulletin. 19 December. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company. Two years of fantastic experiences: Second anniversary of the consular and public diplomacies blog.8/27/2022  This week I am celebrating the second anniversary of the start of this blog. The experience has been fantastic for various reasons. For starters, it has forced me to read and think about many issues that otherwise might have gone unnoticed, from SEO optimization strategies to the decolonization of the study of IR. It has also opened new and exciting opportunities, from posting in the Center of Public Diplomacy blog to communicating with some great thinkers about these topics. It also let me reconnect and become part of a great institution: The DiploFoundation, which is celebrating its 20th anniversary this year. It also encouraged me to be part of a professional organization, the International Studies Association. Being part of it has been an enriching experience, and I was able to present two papers at its 63rd Annual Convention in Nashville, Tennessee, in March. The opportunity to meet Paul Sharp and Iver Neumann was well worth the trip to the indescribable hotel that hosted the event. Even the way I travel has changed since I started blogging because now, I am a lot more aware of the history of the places I visit and how they relate to the history of diplomacy and international relations. It has also sharpened my writing skills and thought processes, helping to prepare better for my lectures. I just started a course to learn how to read French, so I can expand my sources, as there are a lot of works on consular institution history in that language. The blog is also a great way to quickly find different works online. It has become my digital reference tool, although I am now learning to use Zotero. I am aware I have not posted new entries, but I have been reviewing an article for possible publication and working on my first ever book review! I also have at least seven posts in the works that should come out shortly. And now, I ask the readers: How has this blog helped you? Let me know in the comments section.  I have great news for those interested in consular diplomacy. Recently, there have been a few new and fascinating publications on the subject. The evolution of the consular institution. Let´s start with the work of Iver B. Neumann and Halvard Leira, two prominent consular affairs scholars. The chapter “The evolution of the consular institution” of the book Diplomatic Tense (2020) analyzes the development of the consular institution from an evolutionary perspective. This book chapter broadens the authors' previous studies, such as “Consular Representation in an Emerging State: The case of Norway” (2008), “The many past lives of the Consul” (2011), and “Judges, Merchants and Envoys: The Growth and Development of the Consular Institution” (2013). In “the evolution of the consular institution”, Neumann and Leira examine the evolution of the consular functions, using as a reference “tipping points, understood as the culmination of long-term trends.”[i] They evaluate the process based on the concepts of variation, stabilization, and institutionalization of the consular function.[ii] The three tipping points of the consular institution identified are:

It is very interesting to learn how the consular functions of the West Mediterranean influenced the East Mediterranean consular practices. Later, the change of the consular institution came in the opposite direction. Besides, the Hanseatic League´s consular procedures also made their mark on the consular institution before spreading to the rest of the world.[iv] Neumann and Leira dug deeper into the Ottoman Empire´s impact on the extraterritorially of the consuls, also known in the Eastern Mediterranean as capitulations. They also distinguished between the extraterritorial practice used by Europeans in the Mediterranean Sea, which started as a privilege granted by the Muslim rulers to the one applied in East Asia, which was based on domination.[v] Interestingly enough, the extraterritoriality also affected the Western Hemisphere's new republics. In 1838-39, Mexico suffered the French intervention, known as the “Guerra de los Pasteles” or Pastry War, because of the protection of French nationals affected by the country’s continuous civil wars.[vi] The chapter also explains the diplomatization process of consular affairs, which culminated in the 20th century with the complete incorporation of the consulates into the diplomatic realm. The process started as states claimed their sovereignty rights, thus questioning the extraterritoriality activities of foreign consuls at home and turning overseas merchants working as consuls into state employees or at least the designation of local citizens as honorary consuls. The process was slow and uneven; therefore, there were a lot of different variations, even at the beginning of the last century. [vii] At the end of the chapter, the authors ask if an upcoming tipping point could result in the separation of the consular function from diplomacy.[viii] I argue that the opposite is happening. The new tipping point already occurred with the rise of consular diplomacy. I highly recommend not only the chapter “The evolution of the consular institution” but the whole book Diplomatic Tense. It brings a very innovative view of diplomacy from an evolutionary standpoint, using tipping points to understand better its development through the centuries. Besides, it includes various analyses, from how diplomacy is portrayed in the world of Harry Potter to the visual relevance of new ambassadors' accreditation ceremonies and a hegemonic perspective on the physical appearance of diplomats. The role of cities in the development of the consular institution The second work, “The Intercity Origins of Diplomacy: Consuls, Empires and the Sea,” written by Halvard Leira and Benjamin de Carvalho, was published in June 2021 in Diplomatica. A Journal of Diplomacy and Society. In it, the authors “want to prove the connection between cites and diplomacy through problematizing what has counted as diplomacy.”[ix] The article effortlessly links the idea that cities, not states, played a vital role in developing the consular institutions and diplomacy itself. Leira and de Carvalho offer a different angle on diplomacy and its past. By not looking backward with a preconceived notion centered on the state but looking forward from the point of view of cities,[x] they exemplified the importance of city and inter-city relations, with a particular focus on consuls and their role. While Embassies have always represented the whole country, consulates stood for cities and their merchants in gone-bye eras. Therefore, cities were precursors and are still playing an essential role in the evolution of diplomacy even today. For example, in the case of Mexico, its 50 consulates have become a part of their local communities, and from their host city's perspective, they are doing Para diplomacy work. In the blogpost Book review 8: “The meaning of a special relation: Mexico´s relationship with Texas in the light of California´s experience, I referred to the idea that there are city and state diplomacies on the other side of consular diplomacy.[xi] The innovative perspective presented by Leira and de Carvalho helps to revalorize the contributions of the consular institution and practices to the development of diplomacy as we know it today. Furthermore, by destatizing the notion of diplomacy, they open a door for the reevaluation of the consular institution´s past and provide a base for the rise of consular diplomacy. China´s Consular Protection in the 21 Century The third article, “Consular Protection with Chinese Characteristics: Challenges and Solutions” by Liping Xia, is about the evolution of consular assistance of China. From having negligible programs in the past, the government had to work on expanding its consular service due to the ever-growing number of Chinese tourists, investors, and workers traveling overseas. Xia distinguishes unique features of Chinese consular protection, particularly the whole-of-government approach and its inclusion in the national security strategy.[xii] She notes that “China´s highly centralised political system and the current situation of ´big government and small society´ help to account for the local governments´ role in consular protection. “[xiii] Therefore, provincial and municipal authorities share the burden of assisting Chinese nationals abroad, even establishing liaison offices overseas and providing safety training for traveling outside China.[xiv] The enhancement of China´s consular assistance is in line with the evolution of consular diplomacy in other parts of the world. As Leira and Græger explain in the “Introduction: The Duty of Care in International Relation, “the degree of care provided for citizens abroad is thus tied not only to the political system but also to the state capacity, the perceived necessity for domestic legitimacy, and the responsiveness of foreign host governments.”[xv] In the case of China, “ as consular protection is closely related to the rights and interest of ordinary citizen, it becomes a favored window to display the good image of the party and be an effective means to win the hearts and minds of the people.”[xvi] The transformation of China´s consular services to citizens abroad and its different features is a testament to the consolidation of consular diplomacy worldwide in the third decade of the 21st century. Two more studies. There are two more works that I have not read, but they seem to be fascinating. The first is the book Nationals Abroad Globalization, Individual Rights and the Making of Modern International Law (2020) by Christopher A. Casey. According to Doreen Lustig´s review, the work is “a path-breaking account of the history of the rights of aliens and the rights of states to protect national abroad. It is essential reading for anyone interested in the history of diplomatic protection.”[xvii] In today´s world, the consular protection of citizens in distress abroad is the crucial function of consulates worldwide. It is also, as Maaike Okano-Heijmans describes as, an element of consular diplomacy that could affect the national interest due to the attention brought from politicians, the media, and the general public, as argued in her work “The Changes in Consular Assistance and the Emergence of Consular Diplomacy.” The second work is Jan Melissen’s chapter titled “Consular Diplomacy in the Era of Growing Mobility” in the book Ministries of Foreign Affairs in the World: Actors of State Diplomacy (2022). The chapter focus on the communication challenge that MFAs have regarding their citizens traveling and living overseas. “Providing information and assistance to nationals abroad is a major challenge, and governments are well-advised to go about this activity in a more citizen-centric fashion.” I will share my thoughts once I read it. Concluding thoughts The more I learned about the consular institution, the more convinced I am that it is an integral element of a country`s diplomatic efforts, with particular emphasis on public diplomacy. Consuls are the faces of the MFA abroad and at home for most citizens, and their actions can save lives or at least bridge the gap between foreign authorities and institutions and nationals in distress abroad. These recent works all contribute to the reevaluation of consular affairs inside the MFAs, but more importantly, as part of the evolution of diplomacy. You can also read the following blog post that reviews other new publications on consular diplomacy in this link. Besides, here are additional posts about consular diplomacy:

[i] Neumann, Iver N. 2020. “Preface” in Diplomatic Tense, p. xi. [ii] See chapter two “The evolution of diplomacy” for an explanation of the evolutionary perspective of diplomacy. Neumann, Iver N. and Leira, Halvard. 2020. p. 8-25. [iii] Neumann, Iver N. and Leira, Halvard. 2020. “The evolution of the consular institution” in Diplomatic Tense, p. 41. [iv] Ibid. p. 30-34. [v] Ibid. p. 39. [vi] See for example, Gómez Arnau, Remedios. 1990. México y la protección de sus nacionales en Estados Unidos. [vii] Neumann and Leira. 2020. p. 33-40. [viii] Ibid. p. 42. [ix] Leira, Halvard and de Carvalho, Benjamin. 2021. The Intercity Origins of Diplomacy: Consuls, Empires, and the Sea. Diplomatica 3 (1), June, p. 148. [x] Leira and de Carvalho. 2021. P. 149. [xi] Marquez Lartigue, Rodrigo. 2020. Book review 8: “The meaning of a special relation: Mexico´s relationship with Texas in the light of California´s experience” in Mexican Consular Diplomacy in Trump´s Era in Consular and Public Diplomacies Blog. [xii] Xia, Liping. 2021. Consular Protection with Chinese Characteristics: Challenges and Solutions. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 16 (2-3), March, p. 256. [xiii] Xia, Liping. 2021, p. 270. [xiv] Xia, Liping. 2021, p. 260. [xv] Leira, Halvard and Ninga Græger. 2020. “Introduction: The Duty of Care in International Relation” in The Duty of Care in International Relation Protecting Citizens Beyond the Border, p. 4. [xvi] Xia, Liping. 2021, p. 272. [xvii] Lustig, Doreen. 2021. Book Review, Christopher Casey, Nationals Abroad: Globalization, Individual Rights and the Making of Modern International Law. The Law and Practice of International Courts and Tribunals, cited in the book’s webpage. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company.  It was mid-morning in a church in Minneapolis when Maria (not her real name) had her glucose checked as part of the Binational Health Week activities. She was in her mid-forties, and it was the first time she had done it. When the nurse saw the results, she immediately called the doctor. Maria´s sugar levels were sky-high, and she was referred to a local hospital. After three days, Maria was released from the hospital with a diabetes diagnosis. She was unaware of her illness, and her participation in the health fair might have saved her life. This situation is a common occurrence during the yearly celebration of the Binational Health Week (BHW), which is organized by the government of Mexico, through its consular network in the United States, together with the Health Initiative of the Americas, and thousands of allies across the nation, including consular offices of other countries. The program is an outstanding example of Mexico's public-consular diplomacy in the United States focused on preventive health. The BHW has reached millions of people in the 21 years since its creation. It has also promoted the establishment of multiple long-term partnerships, a defining element of 21st-century public diplomacy. Preventive health care is an extraordinary consular assistance program offered by a few countries to its citizens abroad. The BHW was developed to meet the needs of the Mexican community in the United States, a country that has struggled to provide affordable health services to all its population. Besides, the program has promoted a continuous dialogue between health authorities, organizations, and the consular network with immigrant communities. It also encouraged the creation of the Ventanilla de Salud, or Health Desk program, which will be reviewed in another post. The beginning of the Binational Health Week. Since the early 1990s, the Ministry of Health of Mexico has organized yearly multiple health weeks across the nation. During that decade, the Mexican population in the US grew rapidly due to the combination of various factors:

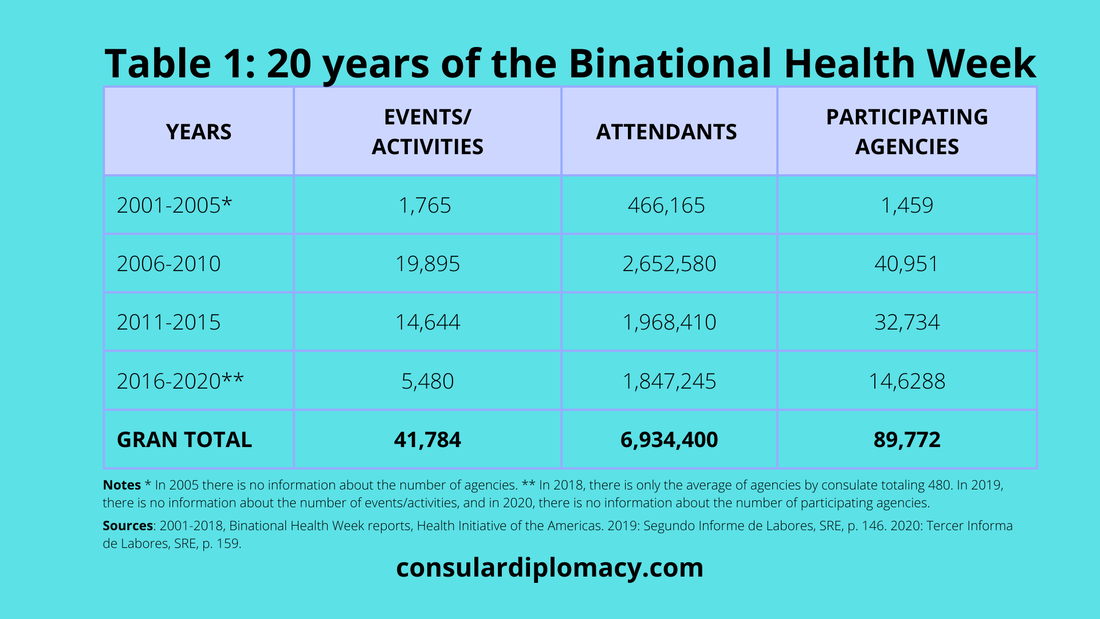

A significant development was the growing number of Mexican women and children moving to the United States, thus demanding new services such as health and education. In California, a significant push for starting the BHW was the passage in 1994 of Proposition 187, “a ballot initiative proposed by anti-immigrant organizations, which restricted undocumented immigrants from the state’s public services, including access to public education and healthcare.” It never came into force but was a hard lesson for the Hispanic community as a whole, not just the Mexican undocumented population in the state. In 2001, the then California-Mexico Health Initiative, now known as the Health Initiative of the Americas (HIA), and the government of Mexico agreed to organize health prevention activities in California in October; thus, the Binational Health Week was born. It started in seven counties, had 98 events and 115 participating agencies, and reached close to 19,000 people. The collaboration between health authorities and related organizations with the consular network deepened through the years, evolving into strategic partnerships across the nation. The evolution of the Binational Health Week, From its humble beginnings in California, the BHW took off like a rocket. It rapidly expanded to other states and, by 2004, it became a national endeavor. The then newly created Institute of Mexican Abroad (IME) and its Advisory Council supported expanding its activities to all the consulates. It was clear that access to health was an important issue, particularly for the new arrival, which comprises a large percentage of women and children, as they reunited with their families in the US due to the end of circular migration of mostly male migrants. Two critical elements of the BHW stand out, which were necessary for its success. One was that opening and closing ceremonies took place alternatively in Mexico and the US, thus making it a genuinely bilateral collaboration. The second element was that it included research activities focused on Hispanic and Mexican health through the celebration of the Binational Public Policy Forum on Migration and Health. The collaboration evolved into a partnership called Research Programs on Migration and Health (PIMSA for its Spanish acronym) that has published significant findings on the subject. Also, since 2008, Mexico´s National Population Council and the HIA have published the Migration and Health reports. The government of Mexico allocated money as seed funding for the organization of the BHW activities. It also invested much time and human capital in the organization, thus demonstrating its commitment to promote preventive health activities. In the beginning, the activities of the BHW concentrated on health fairs. Still, as the program evolved, the organizers incorporated many other services and activities with the support of the Health Desks. For example, according to the 2018 BHW report, 45% of the events were health fairs while 26% were informative sessions, 15% training, and workshops, and 6% conferences and forums. Regarding services, 33% were guidances, 22% screenings, 19% services referrals, 12% medical examinations, and 9% diagnoses. The results of the Binational Health Week. In the 20 years since its creation, 6.9 million people have attended an activity in the framework of the BHW. Nearly 90,000 agencies have participated in more than 40,000 events and activities (see table 1). Besides, the program has been very successful, from lead testing to national events and research projects. For example, from 2003 to 2018, PIMSA sponsored 116 binational research teams and 46 graduate students investing 4.4 million dollars plus over $5 million in additional funding. As mentioned before, it was in the framework of the BHW that the Ventanilla de Salud or Health Desk was developed, being another successful effort of Mexico's public-consular diplomacy. The collaboration between health authorities and related organizations with the consular network deepened through the years, evolving into strategic partnerships across the nation. Working at the Consulate of Mexico in Boston, I had to coordinate the celebration of the first Hispanic health fair in Nashua, New Hampshire, as part of the BHW activities. It was not an easy task, but once the local health authorities understood the idea behind the program, they were thoroughly committed. And it opened the door to more significant interactions between the Mexican community and the city´s residents and authorities. In conclusion, the Binational Health Week is an excellent example of Mexico´s public-consular diplomacy efforts that have benefited close to 7 million people since its creation in 2001 while establishing enduring partnerships. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company. The people of every nation have the right to decide their government, self-determination, and non-intervention. The borders of states must be respected. #StandwithUkraine.  As I mentioned before, I am working on two projects. The first is about global politics. In the previous post, I wrote about the changes in the international system that we are experiencing today. It included some incredible works that I found that make it easier to comprehend these transformations. The second assignment is about public diplomacy and country branding. So, today I am going to write about the latter. I prefer using the term country branding, as it seems more encompassing than nation branding because most states are multination countries, so that a few groups might feel excluded. Other expressions such as place branding, location, and even reputation management are now used as an alternative to nation branding. In one of the blog´s first posts, “Influence and reputation in international affairs: Soft Power and Nation Branding,” I wrote about the differences between public diplomacy, nation brand, and soft power. For me, it was an excellent exercise because there is still much confusion about the three concepts. Even in a textbook focused on public diplomacy, such as the Routledge Handbook on Public Diplomacy (2nd edition), there are a few articles about nation branding, which I really enjoyed, by the way. A lot has happened since Simon Anholt coined the term Nation Brand in 1996. While the first decade of the new millennium seemed to be all about trying to promote a country`s reputation via flashy logos, catchy slogans, expensive spreads in magazines like The Economist, things have seemed to evolve in recent years. I bet that many governments worldwide finally realized that while the country’s image abroad is one of the greatest assets, it cannot be changed using marketing and advertising techniques or spending vast amounts of money on its promotion. In the article “Country Branding: A Practitioner Perspective,”[i] Florian Kaefer, Founder of The Place Brand Observer, details the transformation of place branding from its early heydays to a mature discipline. He just published the book An Insider´s Guide to Place Branding: Shaping the Identity and Reputation of Cities, Regions and Countries, which I hope to read soon because it seems fascinating as it is based on interviews of a significant number of place branding practitioners. The digital world has also changed country branding, including the development of the Digital Country Index of online searches to the creation of the concept of “Selfie Diplomacy.” The Digital Country Index is intriguing as the people search proactively about a country; therefore, there is an assumption of specific interest in a particular nation, which is a measurement of its online attractiveness. However, people worldwide may be searching for a specific country for the wrong reasons from a country branding perspective. Natural or man-made disasters, bad COVID-19 management, or some bad news might not be what the branding manager wants the public to know about the country. For example, just a few days ago, the world focused on Tonga, a Pacific Ocean nation, because of a devastating volcano eruption. So, the online searches index, while usefully, most be treated carefully. As previously mentioned, another example of the changes that place branding experiences in cyberspace is the appealing idea of “Selfie Diplomacy” created by Ilan Manor and Elad Segev. It is defined as “an MFA´s use of social media channels to author a national self-portrait or brand… [and] is thus a form of nation branding conducted via digital platforms”[ii]. It is a country´s digital identity used to broadcast the image that it wants to project in the digital realm. The concept is very intriguing, as everybody now does Selfies. This is just the country´s selfies in the digital realm. Two countries that have stand out in nation branding are Estonia and Costa Rica. Both share the fact that an independent organism coordinates the branding efforts: Enterprise Estonia and Essential Costa Rica. The Baltic national focused on digitalization, including its E-Residency program, while Costa Rica has become a green powerhouse, both activities being at the core of their branding programs. [iii] Something that has not changed is the obsession with indexes. Now, there are so many that it is impossible to keep up with them or even understand the methodology used to rank countries. Here is a brief recompilation of some of them:

For those interested in place branding, there is the International Place Branding Association that offers courses and organizes an annual meeting. It is led by Robert Govers, author of the book Imaginative Communities: Admired cities, regions, and countries. Membership is free, you just have to enroll in their newsletter. Talk about openness! If you are interested in Mexico´s country brand, read the blog post Broken funhouse mirror: Mexico´s image and reputation abroad. [i] Kaefer, Florian. (2019). Country Branding: A Practitioner Perspective. Routledge Handbook on Public Diplomacy (2nd edition) Nancy Snow and Nicholas J. Cull (eds.), pp 129-136. Routledge [ii] Manor, Ilan. (2019). The Digitalization of Public Diplomacy. Palgrave Macmillan, p. 263. See also, Manor Ilan and Segev, Elad. (2015). America´s selfie: How the US portrays itself on its social media accounts. In C Bjola & M Holmes (eds.) Digital diplomacy: Theory and Practice. Routledge. Available at https://digdipblog.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/americas-selfie.pdf [iii] City/Nation/Place (2020) Two countries that prove nation branding works, 10 January. Available at https://www.citynationplace.com/two-countries-that-prove-nation-branding-works [accessed 26 December 2021] DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company.  I am currently working on two new projects. One focuses on world politics, which has been quite interesting because it has allowed me to read and rethink issues that directly impact our planet today. The world order has moved from the stability of the Cold War to the unipolar moment into a process of complex readjustment due to the digital revolution, the rising of new powers, globalization, and the changing features of today`s global power. For most persons, it is hard to visualize these changes, as most international institutions created after World War 2 still exist today, based on the Liberal World Order. Some scholars, like Amitav Acharya, indicate that we are starting to live in a Post-Western World Order based on its predecessor, but significantly different.[1] However, for most Westerners, particularly the United States, it is not a rosy picture, as they stand to lose some of the grips on world politics. As Mark Leonard indicates, the post-cold war ended “with the abrupt and chaotic US withdrawal from Afghanistan.”[2] But, will this new emerging world order will be better for all the people of the world rather than a lucky few? Only time will tell, but let´s hope for the best. To better understand this new world, first, I read The World: A Brief Introduction by Richard Haass of the Council on Foreign Relations. I like it because it covers most of the pressing world issues, from war to the environment, while summarizing the situation of the different regions. The book can help the reader better understand the recent changes of the international system, even if it is a birds-eye view. However, as most International Relations and Politics studies, it is too US-centric. Therefore, there is a need to broaden the different perspectives of what is going around the globe. Maybe this is one of the problems of the chaotic Liberal World Order; it is too dependent on the US. An amazing finding was Rita Giacalone´s book titled Política Internacional a principios del Siglo XXI: Poder, cooperación y conflicto. It is hard to find an easy-to-read book that includes a theoretical framework of geopolitics with specific cases written from a Latin American perspective. This book hits all the right marks. Besides, the research helps comprehend current world affairs, following a simple yet comprehensive analysis of processes, actors, and consequences. It is a true gem and is in Spanish. I have also read the 8th edition of the remarkable textbook The Globalization of World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations, which contains an understandable yet thought-provoking explanation of world politics. It covers a wide variety of issues, including gender and race in international affairs, theoretical perspectives, and even a little bit of history. The authors made an extraordinary effort in presenting dissenting views, including a less Western-centric focus, which is really refreshing. Finally, I discovered by chance the excellent project titled The Power Atlas: Seven battlegrounds of a networked world coordinated by Mark Leonard of the European Council on Foreign Relations. In it, he explains that “In an era in which states use their interdependence against one another, power is no longer defined by control of land or oceans, or even the normative influence of “soft power”. It is now defined by control over flows of people, goods, money, and data, and via the connections they establish. As states compete to control such connections and the dependencies they create, these flows cut across overlapping spheres of influence – shaping the new map of geopolitical power.” [3] This new map covers seven terrains of power, where great powers fight to gain or maintain power while the rest of the world does not have many options. The new perspective on power and the different battlefields where it is fought is eye-opening. It moves away from a traditional outlook to a multilevel chess game where everything is at play at once, from technology to health, in an interconnected and interdependent world. In the essay about culture as one of the battlefields of a networked world, the authors indicate the end of Soft Power due to the lack of attraction of universal ideas and countries' pushback of attempts by others to impose those.[4] This was one of the foundational premises of the Liberal World Order and the view of the “end of history.” Nevertheless, I find it hard to believe that autocratic regimes and illiberal ideas could be attractive in a sustained way for a long-time for many people. But with the recent re-emergence of nationalist and populist movements and the support of narrow majorities, even in the US, I wonder if I am too optimistic, or plainly wrong. Time will tell. Sadly, all these works paint a less bright future of the world. From growing inequality to climate change, humanity faces issues that might result in a return to the “normal” geopolitical fighting, as Leonard says. [5] As the pandemic has clearly demonstrated, humans and countries are not ready to break their geopolitical chains to solve global problems. Simon Anholt explains that there is a need for a dual mandate that includes policies and activities to benefit the country's people and the entire humanity.[6] He demonstrates this idea with his Good Country Index, where top-ranking nations are not the biggest or the most powerful, but the ones that give more to the world than they receive. No wonder countries like Cyprus, Uruguay, Costa Rica, and others are near the top, versus the typical great powers or popular destinations. A final thought: If an alien arrived today and saw the protests in Western countries against vaccine mandates, after more than 5.5 million Covid deaths, and the extreme rise of the SARS-COV-19´s Omicron variant in recent weeks, and negligible levels of vaccinations in many countries, would wonder why humans behave “irrationally,” which has been one of the cornerstones of IR and Foreign Policy Analysis. [1] McGrew, Anthony. Globalization and global politics”. In The Globalization of World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations, 8th edition, Baylis, John, Steve Smith and Patricia Owens (eds), 2020. p. 28-31. [2] Leonard, Mark. “Introduction.” The Power Atlas: Seven battlegrounds of a networked world. European Council on Foreign Relations. 2021. [3] Leonard, Mark. “Introduction.” The Power Atlas: Seven battlegrounds of a networked world. European Council on Foreign Relations. 2021. [4] Krastev, Ivan and Leonard, Mark. “Culture.” The Power Atlas: Seven battlegrounds of a networked world. European Council on Foreign Relations. 2021. [5] Leonard, Mark. “Introduction.” 2021. [6] The Dual Mandate. The Good Country Index. DISCLAIMER: All views expressed on this blog are that of the author and do not represent the opinions of any other authority, agency, organization, employer or company. |

Rodrigo Márquez LartigueDiplomat interested in the development of Consular and Public Diplomacies. Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|